Cohesers and decouplers #

Any project carries many constraints (forces), some of which want for certain parts of its code to be kept together (cohesive) while others push to have them torn apart (decoupled). Their balance and the resulting optimal architecture is very fluid as each of the forces in action depends on the current circumstances, the project’s history and its expected evolution.

Code structure and the level of pain #

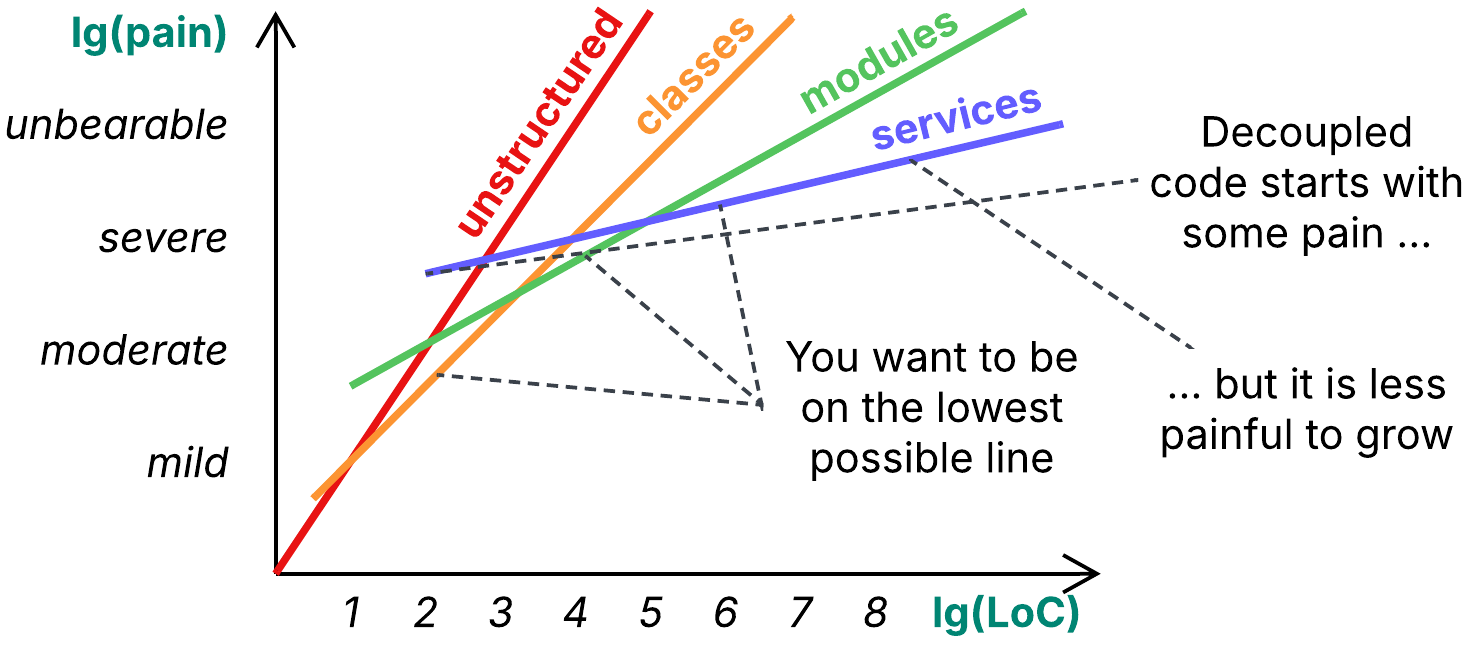

Let’s explore how a force influences the structure of a project. Consider the clarity of code which determines development velocity:

When you have 10 lines of business logic, you are likely to write them down as a simple script. Separating them into classes or deploying 5 services, each running 2 lines of code, is an overkill which would make the complexity of your infrastructure much higher than that of the task on hand.

At 100 lines of code you are likely to be more comfortable with procedures or even classes to divide the code into, as keeping everything together starts to hurt. You switch from the most cohesive implementation to another one, decoupled to an extent. Though the latter is more complex at its core, it allows for less painful growth because it encompasses smaller components.

A file of 5 000 lines is hard to read – you need to separate it into modules, each of which contains classes, which contain methods, which contain the code. You are building yet another level of the hierarchy to keep the number of items in each piece (lines in a method, methods in a class, classes in a module) comfortably small.

At about 100 000 lines you may start considering further separation of your project into services – as, you know, there are merge conflicts, or it takes a while to compile and test the whole codebase… anyway, at that point very few people comprehend the whole thing in detail, thus the benefits of having the entire codebase co-located (monorepo) are diminishing while new drawbacks emerge.

Building a hierarchy #

As we see from the example above, code clarity favors cohesiveness (everything together) for smaller codebases but decoupling (parts separated with narrow interfaces) for larger projects. We can state that the direction the force under review (clarity) pushes us in depends on the project’s size. That is not a unique case – many forces work this way, resulting in the famous Monolith vs Microservices complexity diagram.

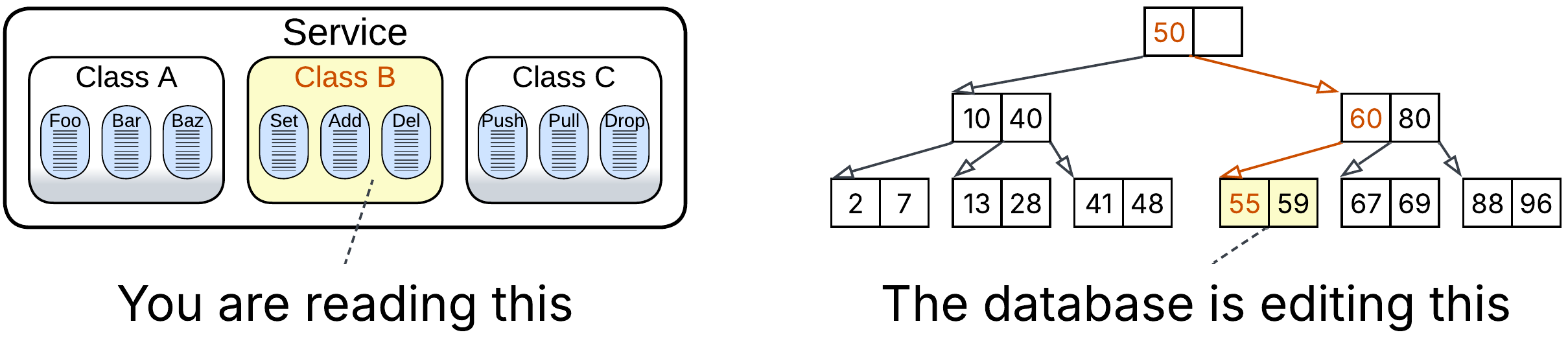

Such a behavior is common for forces and, by the way, it is also the case with editing sorted data. Array is the most efficient data structure for a small collection (up to about 1 000 elements) while anything larger requires a hash map or B-tree (hierarchy of arrays). Just as a database splits oversized arrays because they are too slow to edit, the human mind is inefficient with large collections of similar items and wants them to be restructured into a hierarchy. When we look into a service, we see only the classes it contains. When we examine a class, we check the list of its methods, not those of surrounding classes. And when we open a method, we try to understand how its lines of code work together. This is the way humans fight complexity – by selecting a segment at one level of abstraction and ignoring everything around.

A hierarchy inherently adds some inconvenience – traversing levels of a B-tree slows down operations, and a project with many files takes time to grasp – which is why we avoid deep hierarchies in smaller projects (or datasets) – but that is still a very low cost for having any individual component (a method, class or module in a project; an array in a B-tree) stay reasonably small and simple thanks to the distribution of the overall complexity (or data) over the hierarchy.

Bidirectional forces #

Among the forces that prefer decomposing a project into segments of certain size are:

- Clarity – as discussed above.

- Development velocity – programmers are very productive when they know their code and don’t waste their time on communication. Still, there is a productivity limit for a single person, and if you want your project to be developed faster than that, you need to divide it among several teams, sacrificing individual performance for brute force.

- Latency – it is poor for a distributed system, but is not much better for a large monolith that may deadlock. Ideally, you should separate the latency-critical part into a dedicated small component placed close to the input and output hardware.

- Throughput – on one hand, interservice communication is suboptimal because of the associated networking and serialization. On the other hand, there is a limit for a single server’s performance as more powerful hardware is too expensive. It is cheaper to install several commodity servers and accept a communication penalty than keep the entire system running on a single high-end machine to avoid networking.

- Security – a single process is easier to audit and secure than a system of services. However, as a service grows, it may develop multiple interfaces and assimilate many libraries. Eventually, protecting that mishmash becomes much harder than creating a secure perimeter around a distributed system.

Cohesers #

Other forces predominantly push you towards merging all your code and data together:

- Debuggability – it is hard to debug a distributed system. You need to investigate logs and attach your debugger to several services which may be written in different programming languages. Debugging a single process, even 10 MLoC in size, is almost always easier (except when it is undocumented).

- Data consistency – when everything runs in a single thread, you don’t have to care about data races, lost packets, or idempotence. The CAP theorem is on your side.

- Data analysis – it is hard to collect data from multiple sources. You cannot use SQL joins. However, at some point in the distant future, you may still reach the performance limit of your single database, in theory making data analysis a kind of bidirectional force.

Decouplers #

And there are forces that try to keep your code fragmented:

- Variability – if your project needs to satisfy many conflicting requirements, it is very hard to achieve that with a uniform codebase running in a single process.

- Location – you may need to run parts of your system on its end users’ devices, in regional data centers, or even on specialized hardware.

- Organizational structure – according to Conway’s law, forcing everyone to work on a shared component is among the top team performance killers, especially when time zone differences are involved.

Expansion and contraction #

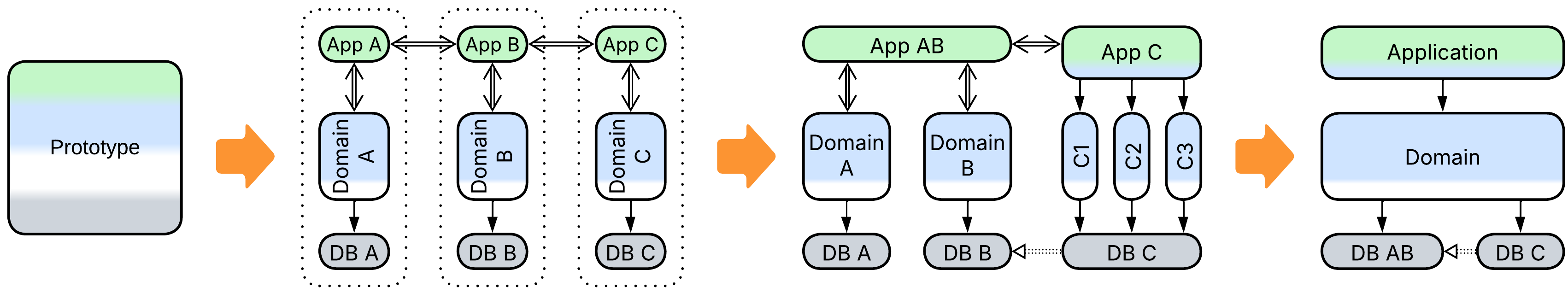

As was discussed previously, when you start a project by building a PoC or prototype, you have little code and need to move quickly. Most of the decouplers are not there and the bidirectional forces favor cohesion, thus you don’t waste your time on extra interfaces or fine-grained services. You don’t have multiple teams to fall prey to Conway’s law.

As soon as the prototype is approved, it’s time to prepare for iterative development of a project which nobody comprehends in advance. Requirements will change many a time. Libraries and frameworks may not work as expected. External services may die or change. Your team members may leave or, worse, be eager to try a newer technology. You need all the flexibility in the world, and the flexibility comes through decoupling. But you also rely on your speed to remain ahead of competitors, therefore you cannot go too far because decoupling is not free. You try to imagine what may change in the future and prepare by isolating the would-be affected parts with well-defined interfaces.

As your software matures, the flow of changes slows down and the business becomes more predictable or, rather, more familiar. You observe that some of the interfaces which you’ve added have never been put to real use – they just make the project more complex – you pay for decoupling without earning its benefits. Others have been found to be too restrictive and were removed. Thus the system begins to contract, burning the flexibility it no longer needs while also growing in directions that were not originally expected.

Finally, you move to the support phase. The best programmers leave for more active projects. Whoever replaces them does not know the code. The remaining flexibility decomposes in favor of quick hackarounds. What remains is an ugly cohesive evolutionary-shaped mess, created through generations of ad-hoc patches.