Architecture and product life cycle #

In my practice, a product’s architecture changes over its lifetime. For a R&D, when there is nobody with relevant experience on the team, it starts small, gradually gains flexibility through fragmentation, grows and restructures itself according to the ever-changing domain knowledge and business requirements, then it solidifies as the project matures and dies to performance optimizations and loss of experience as main programmers leave. In more mundane projects the first stages may be omitted, as little research needs to be done, and oftentimes a project is canceled way before its architecture succumbs under its own weight. Anyway, let’s observe the full life cycle.

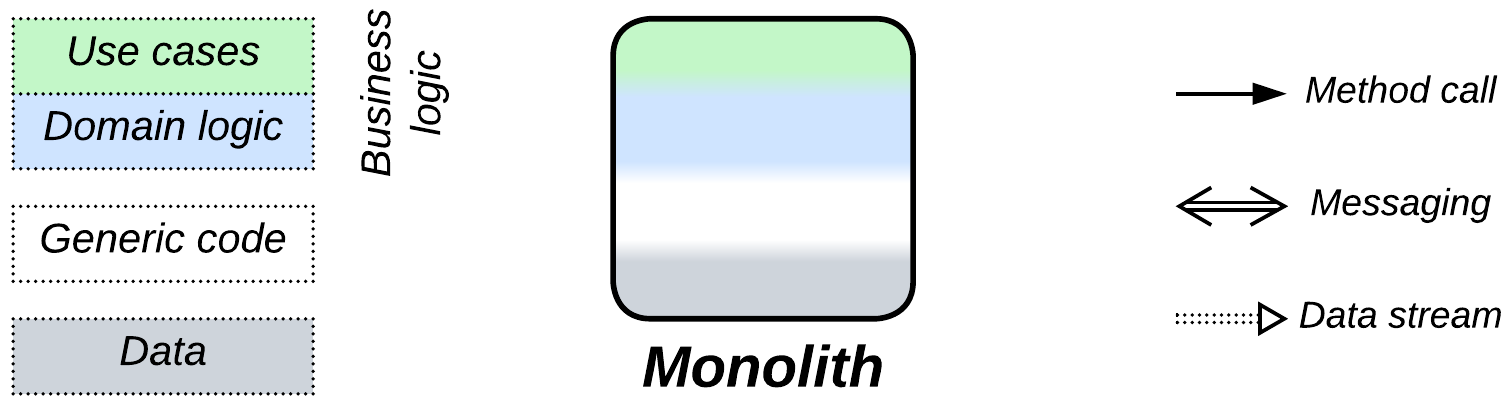

Infancy (proof of concept) – Monolith #

A project in an unknown domain starts humble and small, likely as a proof of concept. You need to write quickly to check your ideas about how the domain works without investing much time – as you may oftentimes be wrong here or there, making you rethink and rewrite.

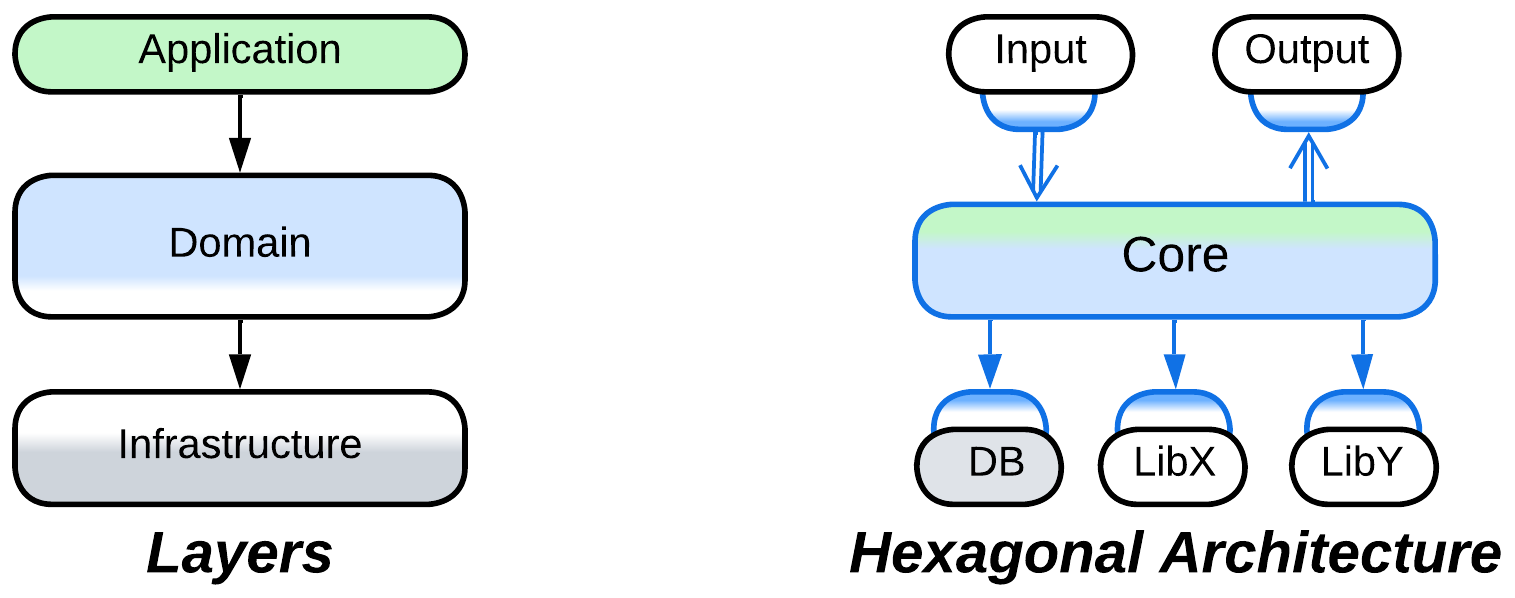

Childhood (prototype) – Layers #

When you have the thing working, you may start reflecting on the rules and the code you wrote. What belongs where, what can be subject to change, which tests will you need? At this point you clearly see the levels of abstractness: the high-level application (integration, orchestration) logic, the lower-level domain (business) rules, and the generic infrastructure [DDD]. Now that you know better the whats and the hows, you divide the code (either old or rewritten from scratch) into Layers or Hexagonal Architecture to make it both structured and flexible, still without heavy development overhead caused by interfaces between subdomains.

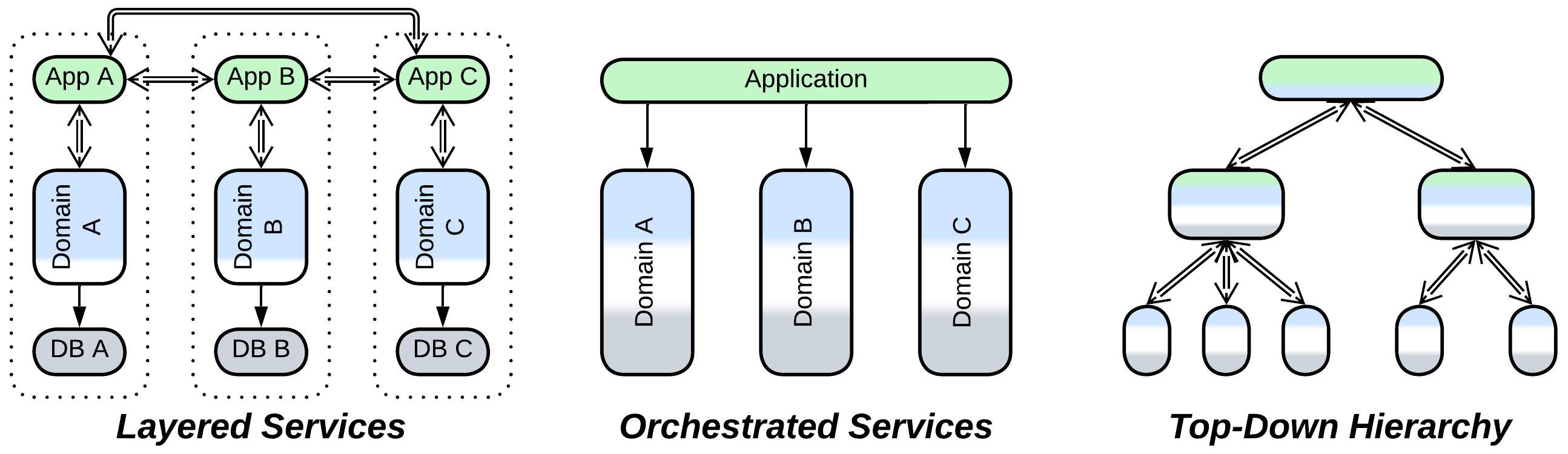

Youth (development of features) – fragmented architectures #

As you acquire domain experience, you start discerning subdomains (or bounded contexts [DDD]) and isolating them to reduce the complexity of your code. The layered structure turns into a system of subdomain-dedicated components: modules, services, device drivers – whatever you used to name them throughout your career. The actual architecture follows the structure of the domain, with Layered Services, Orchestrated Services, and Top-Down Hierarchy among common examples. The fragmentation of the system enables development by multiple teams with diverse technologies and styles, reduces ripple effect of changes, and helps testability. However, use cases for the system as a whole become harder to understand and fix – if only because they traverse the parts of the code owned by multiple teams – which is not extremely bad given you have enough humanpower to do the work.

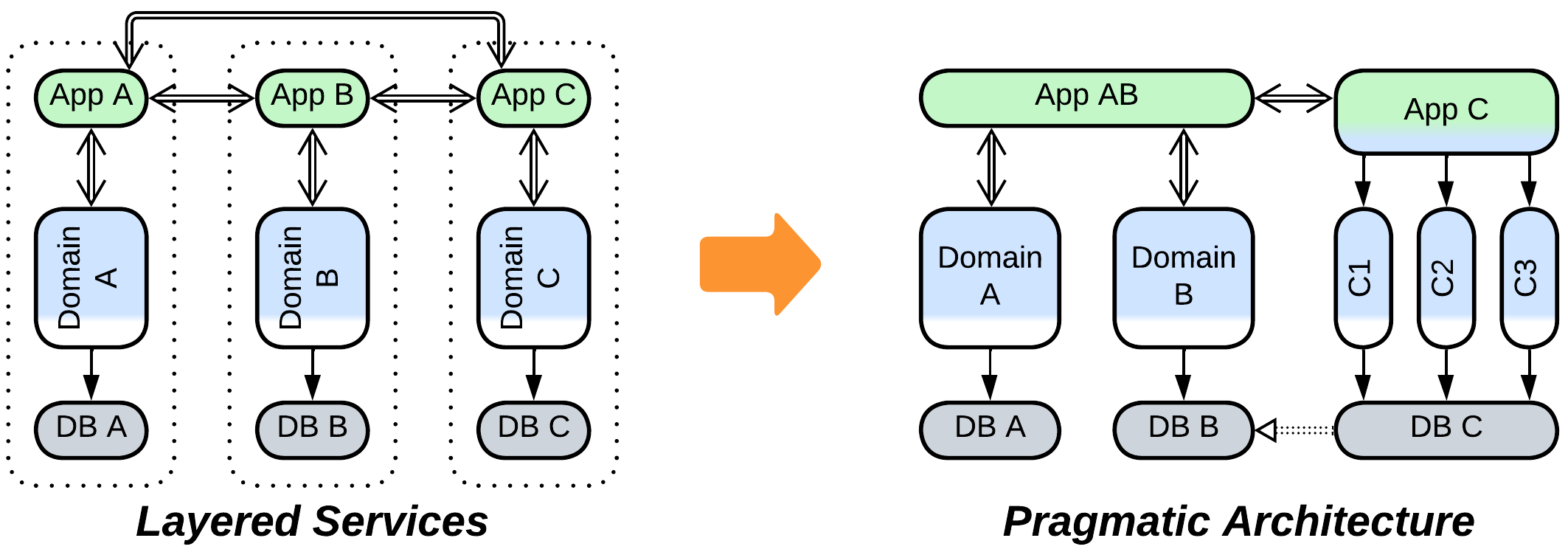

Adulthood (production) – ad-hoc composition #

As the product enters the market, its development tends to slow down with more attention given to corner cases and user experience. Some (often the most active) people are going to get bored and leave the project, while your understanding of the domain changes again based on user experience and real-life business needs [DDD]. You may find that some of the components which you have designed as independent become strongly coupled, and you are lucky if they are small enough to be merged together – this is where the fragmentation from the previous stage pays off. Other parts of the system may outgrow the comfort zone of programmers and need to be subdivided. The architecture becomes asymmetrical and pragmatic.

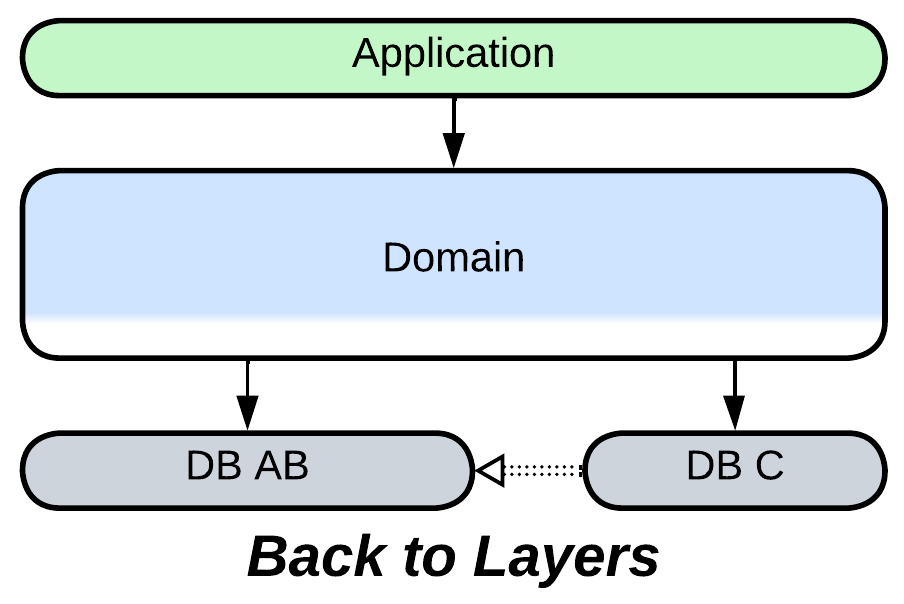

Old age (support) – back to Layers #

When active development ceases, you lose even more people and funding as you drift into the support phase. You are unlikely to retain your best programmers – you’ll get novices or even an outsourced team instead. They will struggle to retain the structure of the system – with its mass of hacks from the previous years – against progressively more weird requests from the business and customers whose natural desires have already been satisfied. That will cause many more hacks to be added – and components coupled or merged for the hacks to land – bringing the architecture back to Layers, though this time heavily oversized layers.

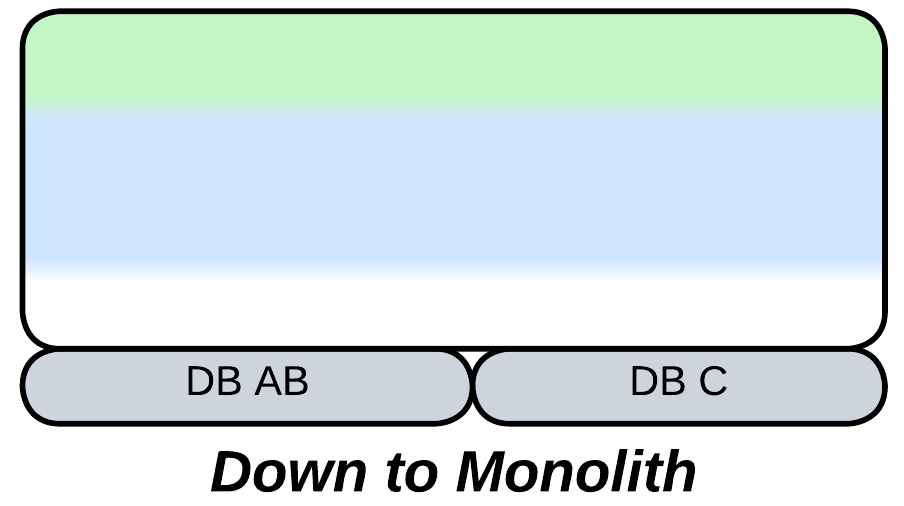

Death (the ultimate release) – Monolith #

If the project is allowed to die, it may still have a chance of a final release which aims at improving performance and leaving a golden standard for the generations of users to come. Heavy optimizations will likely require merging the layers to avoid all kinds of communication overhead, reverting the system back to Monolith.

So it goes #

Even though I have observed the cycle of architecture expanding and collapsing in embedded software, I believe that these forces apply to most kinds of systems. First you need to go quickly and interfaces are a burden. Then you need the extra flexibility that they provide to reserve space for future design changes. And as the flow of changes ceases, you may optimize the flexibility away to make programming easier and the code smaller and faster. However, the last transition is not always applicable: a distributed system will oppose compacting if it was written in diverse programming languages or needs specialized hardware setups for proper operation.

Going back in time #

It can happen that you need to step back through the life cycle – for example, when the domain itself changes drastically: a new standard emerges or the management decides that your application for washing machines fits coffee machines pretty well, as they are basically doing the same things: heating water, adding powder, and stirring – but you have never wrote software for coffee machines before, thus you are back to the R&D phase.

In such cases it may be easier to rewrite the affected components from scratch rather than try to rejuvenate and refit the old code. Remember that you keep your experience – what was originally implemented as an improvised hack will be accounted for in the redesigned architecture. This means that every time a component is rewritten adds to its longevity as its architecture fits the domain more closely and needs fewer hacks (which are inflexible and confusing by definition) to get to production.