Hexagonal Architecture #

Trust no one. Protect your code from external dependencies.

Known as: Hexagonal Architecture, or originally as Ports and Adapters.

Variants:

By placement of adapters:

- Adapters on the external component’s side.

- Adapters on the core side.

Examples – Hexagonal Architecture:

- Hexagonal Architecture / Ports and Adapters,

- DDD-Style Hexagonal Architecture [LDDD] / Onion Architecture / Clean Architecture.

Examples – Separated Presentation:

- (Layered) Model-View-Presenter (MVP), Model-View-Adapter (MVA), Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM), Model 1 (MVC1), Document-View [POSA1],

- (Pipelined) Model-View-Controller (MVC) [POSA1, POSA4] / Action-Domain-Responder (ADR) / Resource-Method-Representation (RMR) / Model 2 (MVC2) / Game Development Engine.

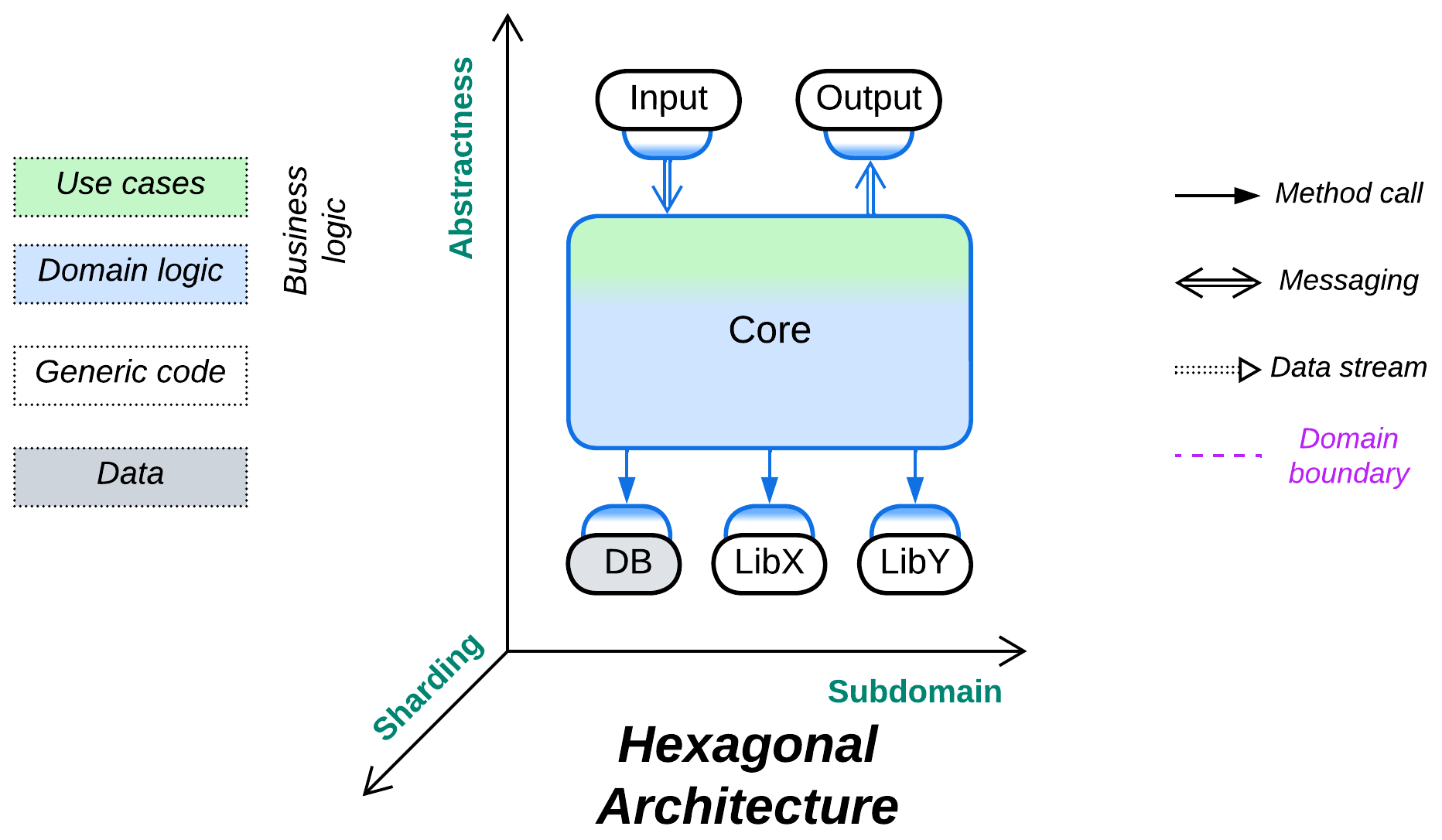

Structure: A monolithic business logic extended with a set of (adapter, component) pairs that encapsulate external dependencies.

Type: Implementation.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Isolates business logic from external dependencies | Suboptimal performance |

| Facilitates the use of stubs/mocks for testing and development | The vendor-independent interfaces must be designed before the start of development |

| Allows for qualities to vary between the external components and the business logic | |

| The programmers of business logic don’t need to learn any external technologies |

References: Herberto Graça’s chronicles is the main collection of patterns from this chapter. Hexagonal Architecture has the original article and a brief summary of its layered variant in [LDDD]. Most of the Separated Presentation patterns are featured on Wikipedia and there are collections of them from Martin Fowler, Anthony Ferrara and Derek Greer.

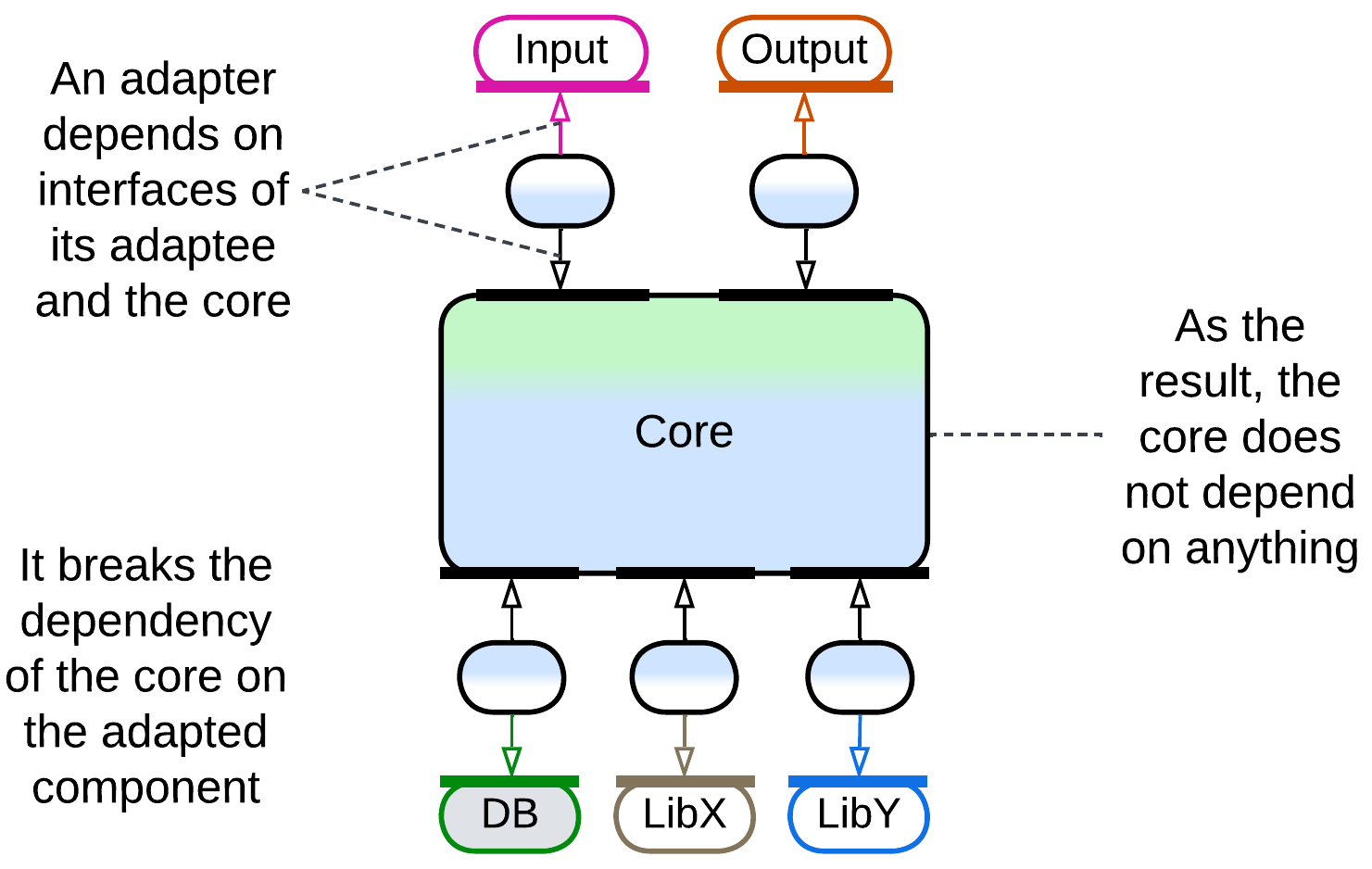

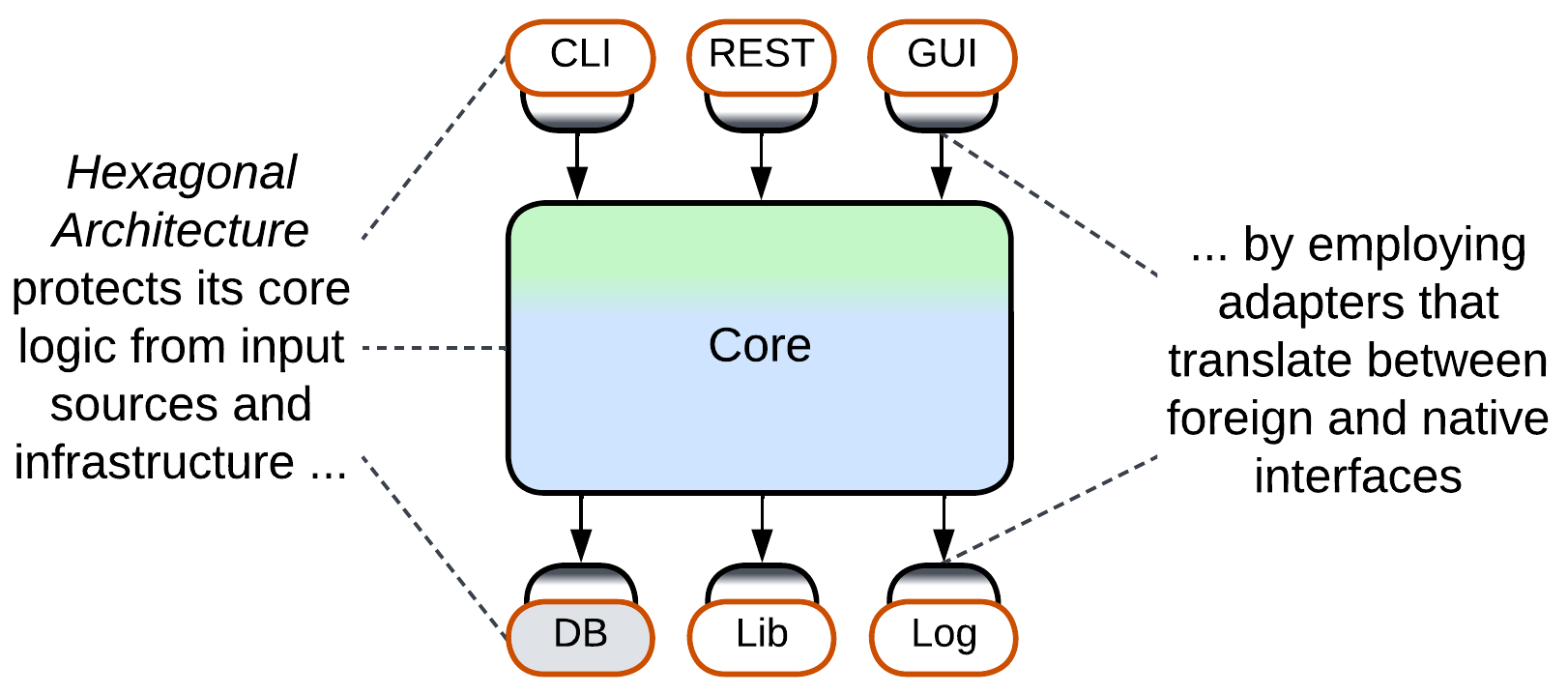

Hexagonal Architecture is a variation of Plugins that aims for total self-sufficiency of business logic. Any third-party tools, whether libraries, services or databases, are hidden behind adapters [GoF] that translate the external module’s interface into a service provider interface (SPI) defined by the core module and called port. The core’s business logic depends only on the ports that its developers defined – a perfect use of dependency inversion – and manipulates interfaces that were designed in the most convenient way. The benefits of this architecture include the core’s cross-platform nature, easy development and testing with stubs or mocks, support for event replay and protection from vendor lock-in. It also allows for replacement of any external library at late stages of the project. The flexibility is paid for with a somewhat longer system design stage and lost optimization opportunities. There is also a high risk to design a leaky abstraction – an SPI that looks generic but whose contract matches that of the component it encapsulates, making it much harder than expected to change the component’s vendor.

Stubs and mocks are test doubles – simplistic replacements for real-world components. They are used to run the business logic in isolation – without the need to deploy any heavyweight libraries or services the logic may depend upon. A stub supports a single usage scenario in a single test case while a mock is more generic – its behavior is programmed on a per test basis.

Performance #

Hexagonal Architecture is a strange beast performance-wise. The generic interfaces (ports) between the core and adapters stand in the way of whole-system optimization and may add context switching. Still, at the same time, each adapter concentrates all the vendor-specific code for its external dependency, which makes the adapter a perfect single place for aggressive optimization by an expert or consultant who is proficient with the adapted third-party software but does not have time to learn the details of your business logic. Thus, some opportunities for optimization are lost while others emerge.

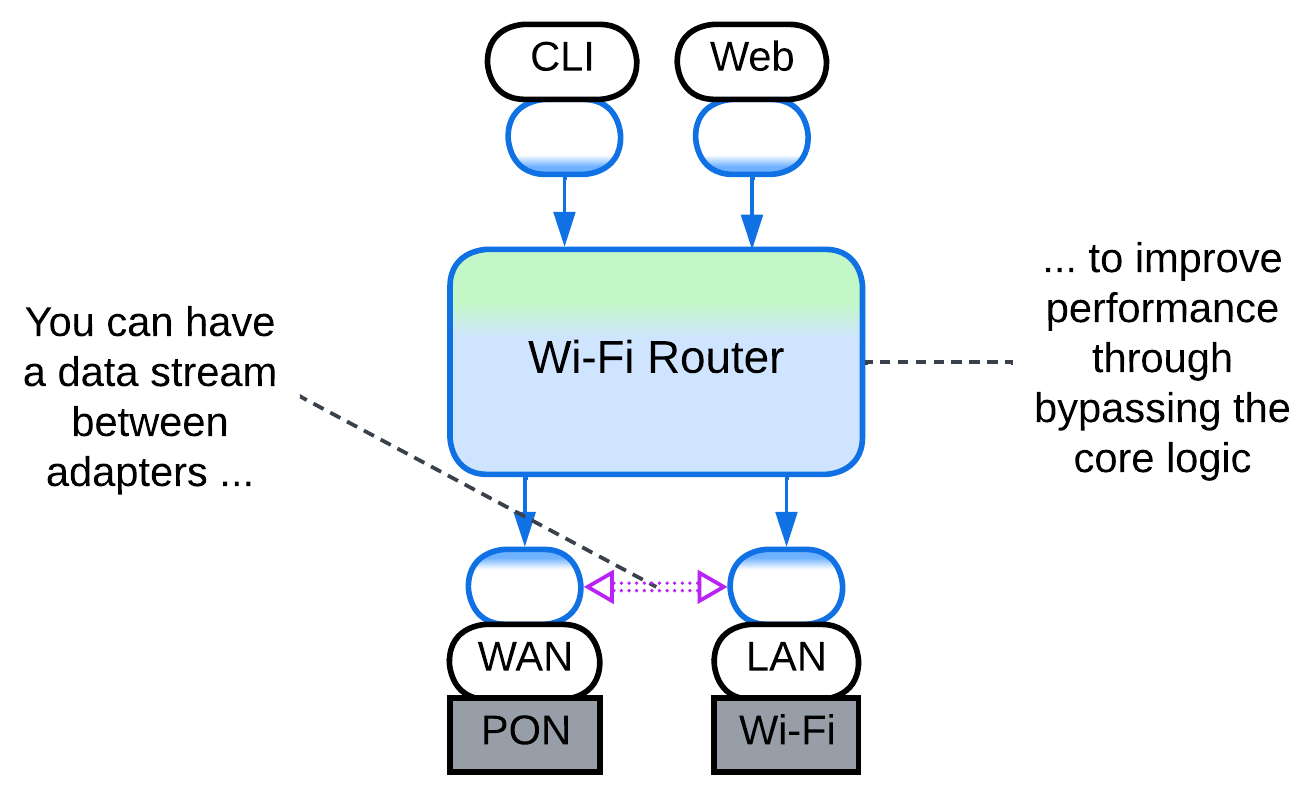

In rare cases the system may benefit from direct communication between the adapters. However, that requires several of them to be compatible or polymorphic, in which case your Hexagonal Architecture may in fact be a kind of shallow Hierarchy. Examples include a service that uses several databases which are kept in sync through Change Data Capture (CDC) or a telephony gateway that interconnects various kinds of voice devices.

Dependencies #

Each adapter breaks the dependency between the core that contains business logic and an adapted component. This makes all the system’s components mutually independent – and easily interchangeable and evolvable – except for the adapters themselves, which are small enough to be rewritten as need arises.

Applicability #

Hexagonal Architecture benefits:

- Medium-sized or larger components. The programmers don’t need to learn details of external technologies and may concentrate on the business logic instead. The code of the core becomes smaller as all the details of managing external components are moved into their adapters.

- Cross-platform development. The core is naturally cross-platform as it does not depend on any (platform-specific) libraries.

- Long-lived products. Technologies come and go, your product remains. Always be ready to change the technologies it uses.

- Unfamiliar domain. You don’t know how much load you’ll need your database to support. You don’t know if the library you selected is stable enough for your needs. Be prepared to replace vendors even after the public release of your product.

- Automated testing. Stubs and mocks are great for reducing load on test servers. And stubs for the SPIs which you wrote yourself are easy as a pie.

- Zero bug tolerance. SPIs allow for event replay. If your business logic is deterministic, you can reproduce your user’s bugs in your office.

Hexagonal Architecture is not good for:

- Small components. If there is little business logic, there is not much to protect, while the overhead of defining SPIs and writing adapters is high compared to the total development time.

- Write-and-forget projects. You don’t want to waste your time on long-term survivability of your code.

- Quick start. You need to show the results right now. No time for good architecture.

- Low latency. The adapters slow down communication. This is somewhat alleviated by creating direct communication channels between the adapters to bypass the core.

Relations #

Hexagonal Architecture:

- Is a kind of Plugins.

- May be a shallow Hierarchy.

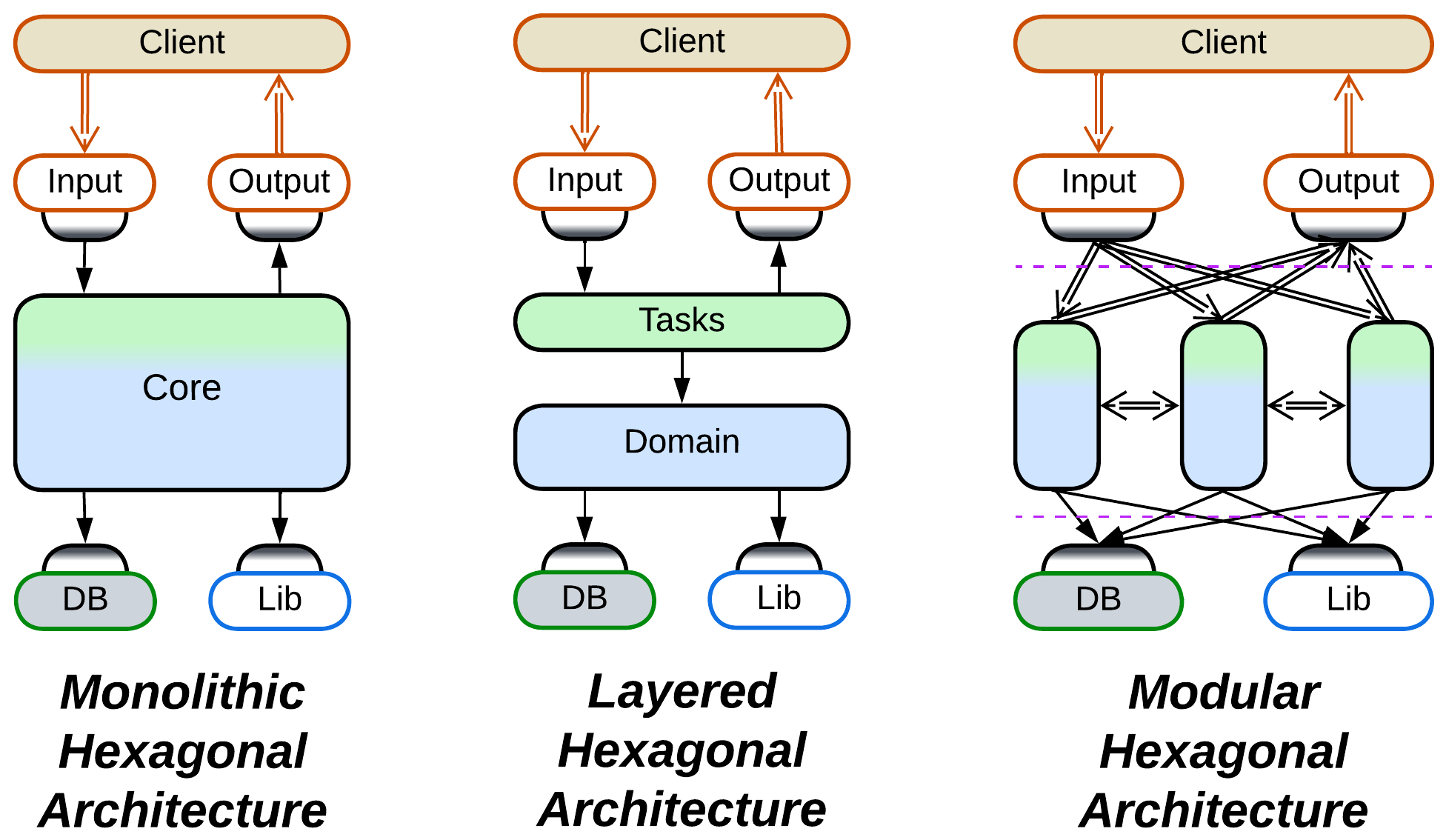

- Implements Monolith or Layers.

- Extends Monolith, Layers or, rarely, Services with one or two layers of services.

- The MVC family of patterns is also derived from Pipeline.

Variants by placement of adapters #

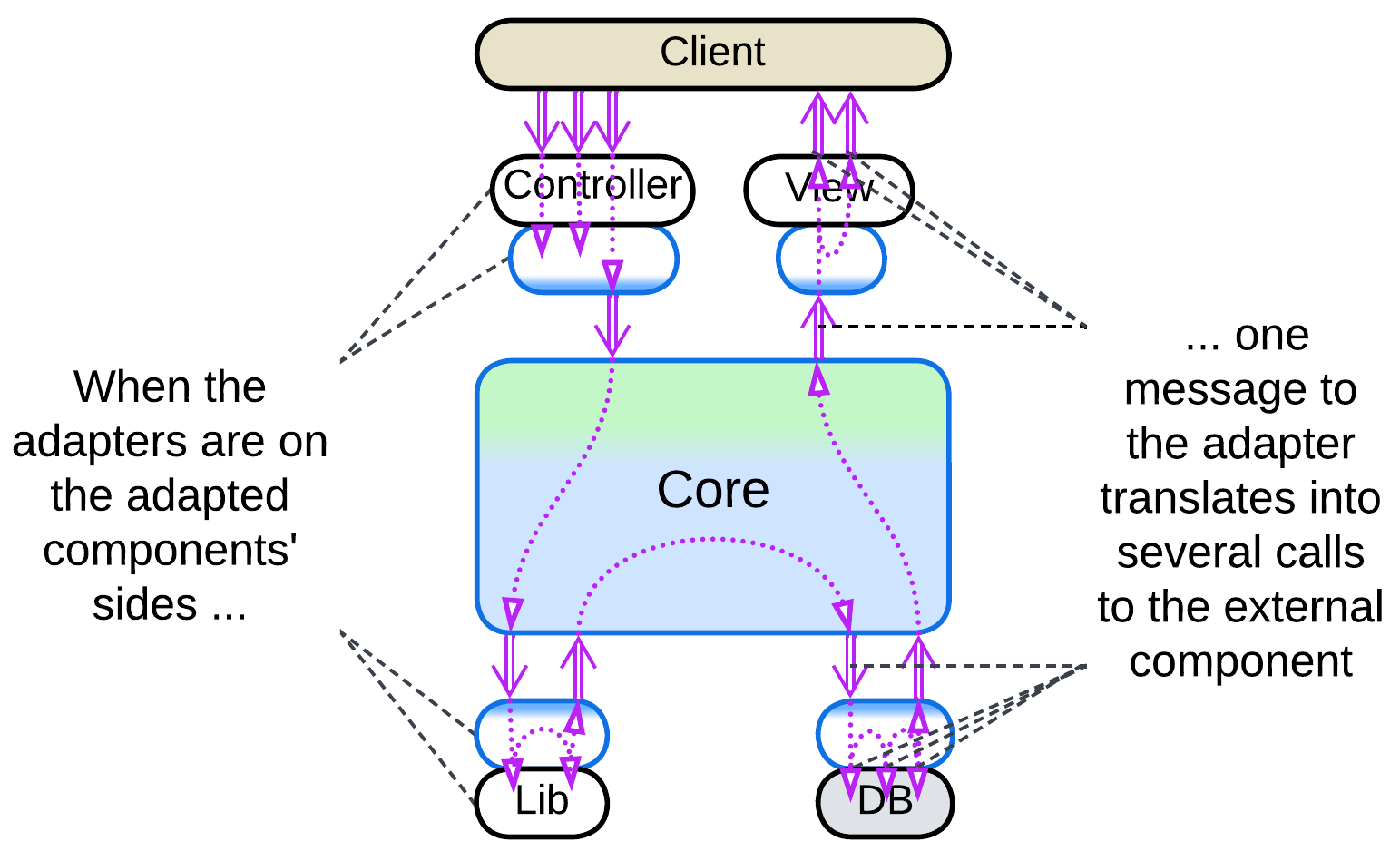

One possible variation in a distributed or asynchronous Hexagonal Architecture is the deployment of adapters, which may reside adjacent to the core or with the components they adapt:

Adapters on the external component side #

If your team owns the component adapted, the adapter may be placed next to it. That usually makes sense because a single domain message (in the terms of your business logic) tends to unroll into a series of calls to an external component. The fewer messages you send, the faster your system is.

This resembles Sidecar [DDS] and Open Host Service [DDD].

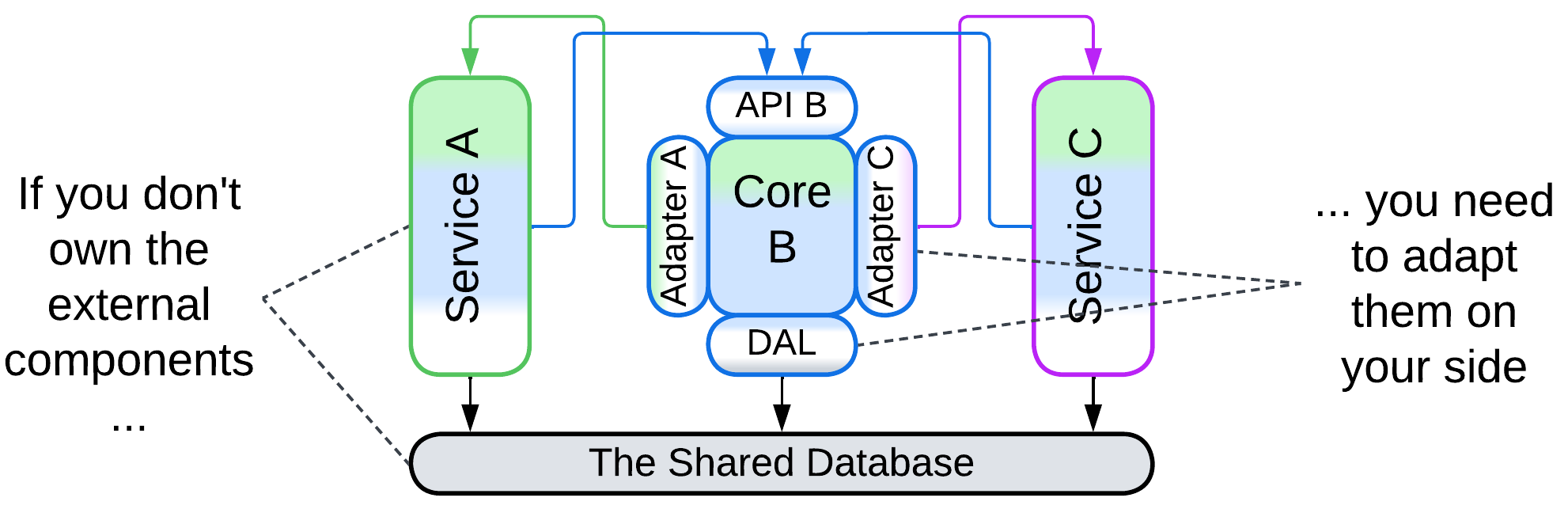

Adapters on the core side #

Sometimes you need to adapt an external service which you don’t control. In that case the only real option is to place its adapter together with your core logic. In theory, the adapter can be deployed as a separate component, maybe in a Sidecar [DDS], but that may slow down communication.

This approach resembles Ambassador [DDS] and Anticorruption Layer [DDD].

Examples – Hexagonal Architecture #

Hexagonal Architecture protects business logic from all its dependencies. It is simple and unambiguous. It does not come in many shapes:

Hexagonal Architecture, Ports and Adapters #

Just like MVC it is based on, the original Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters) does not care about the contents or structure of its core – it is all about isolating the core from the environment. The core may have layers or modules or even plugins inside, but the pattern has nothing to say about them.

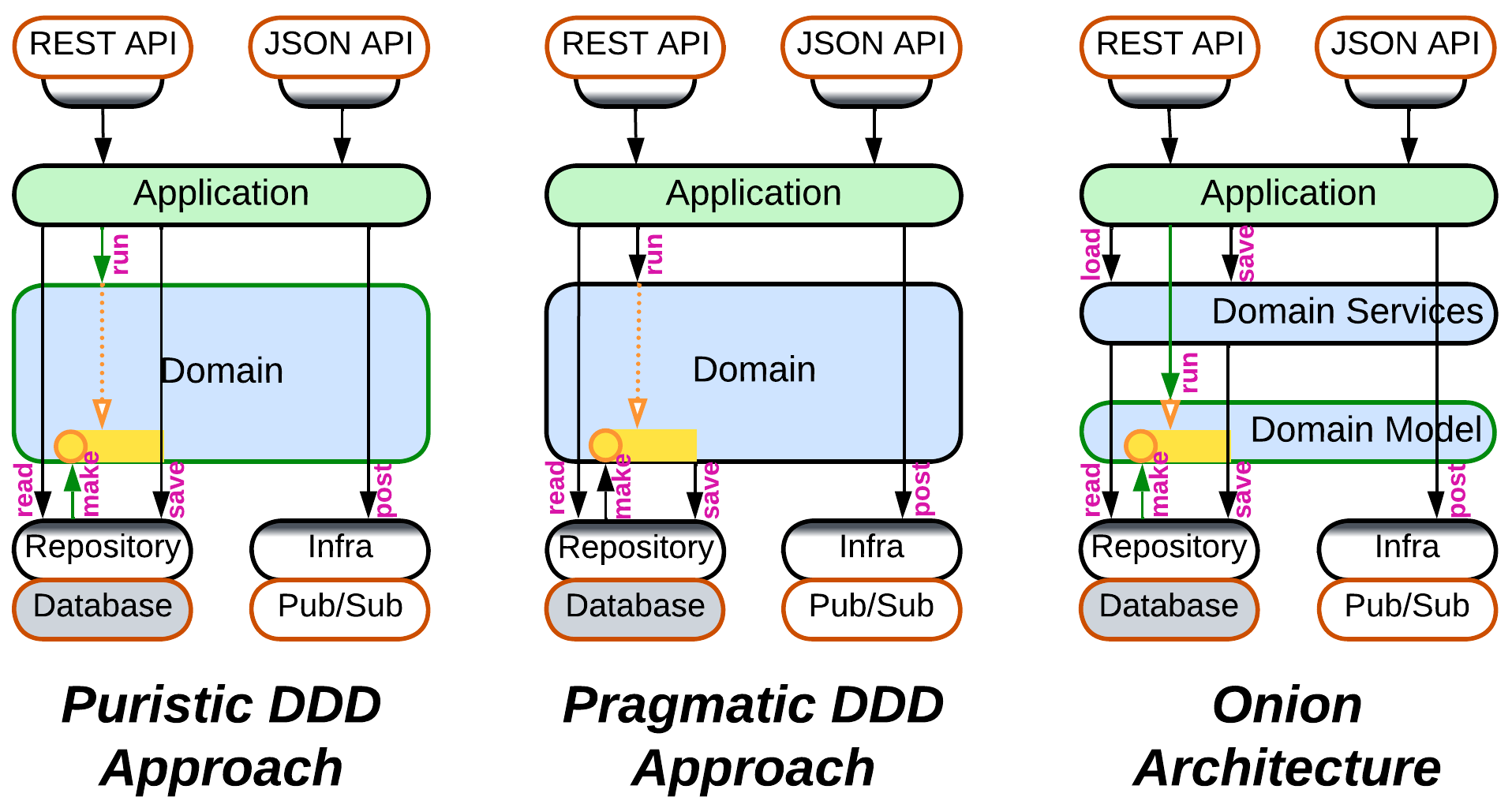

DDD-Style Hexagonal Architecture, Onion Architecture, Clean Architecture #

As Hexagonal Architecture built upon the DDD’s idea of isolating business logic with Adapters, it was quickly integrated back into DDD [LDDD]. However, as Ports and Adapters appeared later than the original DDD book, there is no universal agreement on how the thing should work:

- The cleanest way is for the domain layer to have nothing to do with the database – with this approach the application asks the repository (the database adapter) to create aggregates (domain objects), then executes its business actions on the aggregates and tells the repository to save the changed aggregates back to the database.

- Others say that in practice the logic inside an aggregate may have to read additional information from the database or even depend on the result of persisting parts of the aggregate. Thus it is the aggregate, not the application, which should save its changes, and the logic of accessing the database leaks into the domain layer.

- Onion Architecture, one of early developments of Hexagonal Architecture and DDD, always splits the domain layer into a domain model and a domain services. The domain model layer contains classes with business data and business logic, which are loaded and saved by the domain services layer just above it. And the upper application services layer drives use cases by calling into both domain services and domain model.

- There is also Clean Architecture which seems to generalize the approaches above without delving into practical details – thus the way it saves its aggregates remains a mystery.

Examples – Separated Presentation #

Separated Presentation protects business logic from a dependency on presentation (interactions with the system’s user via a window, command line, or web page). There is a great variety of such patterns, commonly known as Model-View-Controller (MVC) alternatives. They are derived from Hexagonal Architecture by omitting every component not directly involved in user interactions and make three structurally distinct groups:

- Bidirectional flow – the view (user-facing component) both receives input and produces output and there is often an explicit adapter between it and the main system, resulting in Layers.

- Unidirectional flow – the controller receives input while the view produces output, forming a kind of Pipeline.

- Hierarchical with multiple models, discussed in the Hierarchy chapter.

All of them aim at making the business logic presentation-agnostic (thus cross-platform and developed by an independent team), but differ in their complexity, flexibility and best use cases.

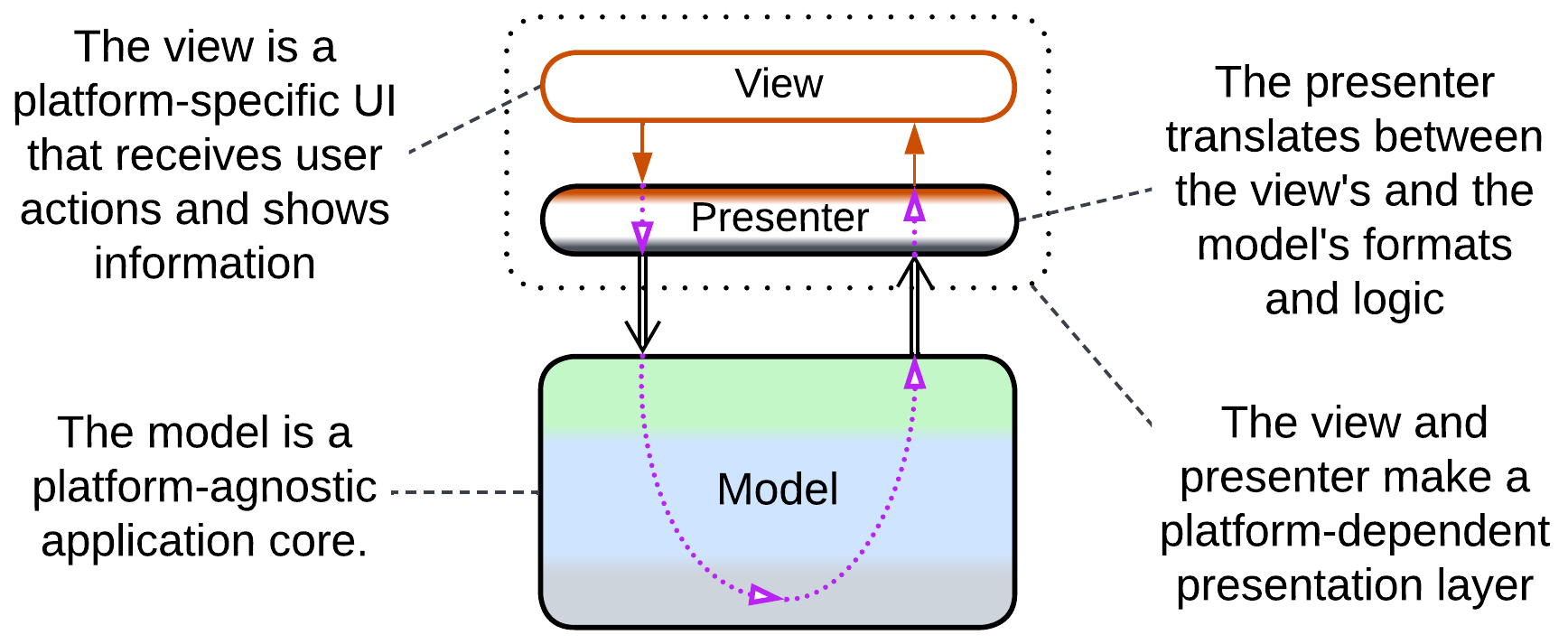

Model-View-Presenter (MVP), Model-View-Adapter (MVA), Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM), Model 1 (MVC1), Document-View #

MVP-style patterns pass user input and output through one or more presentation layers. Each pattern includes:

- View – the interface exposed to users.

- An optional intermediate layer that translates between the view and model. It is the component which differentiates the patterns, both in name and function.

- Model – the whole system’s business logic and infrastructure, now independent from the method of presentation (CLI, UI or web).

Document-View [POSA1] and Model 1 (MVC1) skip the intermediate layer and connect the view directly to the model (document). These are the simplest Separated Presentation patterns for UI and web applications, correspondingly.

In a Model-View-Presenter (MVP), the presenter (Supervising Controller) receives input from the view, interprets it as a call to one of the model’s methods, retrieves the call’s results and shows them in the view, which is often completely dumb (Passive View). A complex system may feature multiple view-presenter pairs, one per UI screen.

A Model-View-Adapter (MVA) is quite similar to MVP, but it chooses the adapter on a per session basis while reusing the view. For example, an unauthorized user, a normal user, and an admin would access the model through different adapters that would show them only the data and actions available with their permissions.

A Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) uses a stateful intermediary (ViewModel or Presentation Model) which resembles a Response Cache, Materialized View, Reporting Database or Read Model of CQRS – it stores all the data shown in the view in a form which is convenient for the view to bind to. Changes in the view are propagated to the ViewModel which translates them into requests to the underlying application (the true model). Changes in the model (independent or resulting from user actions) are propagated to the ViewModel and, eventually, to the view.

All those patterns exploit modern OS or GUI frameworks’ widgets which handle and process mouse and keyboard input, thus removing the need for a separate (input) controller (see below).

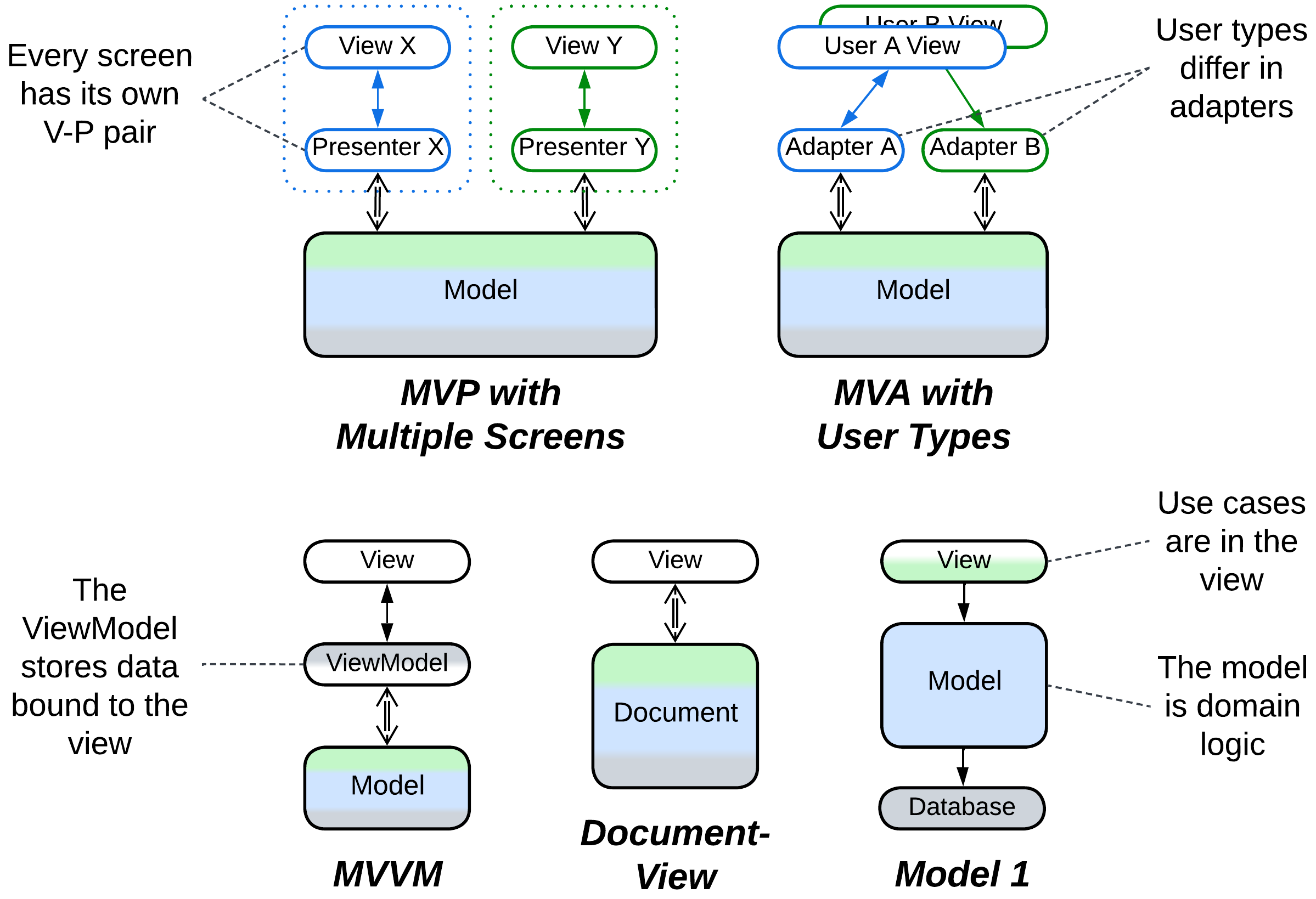

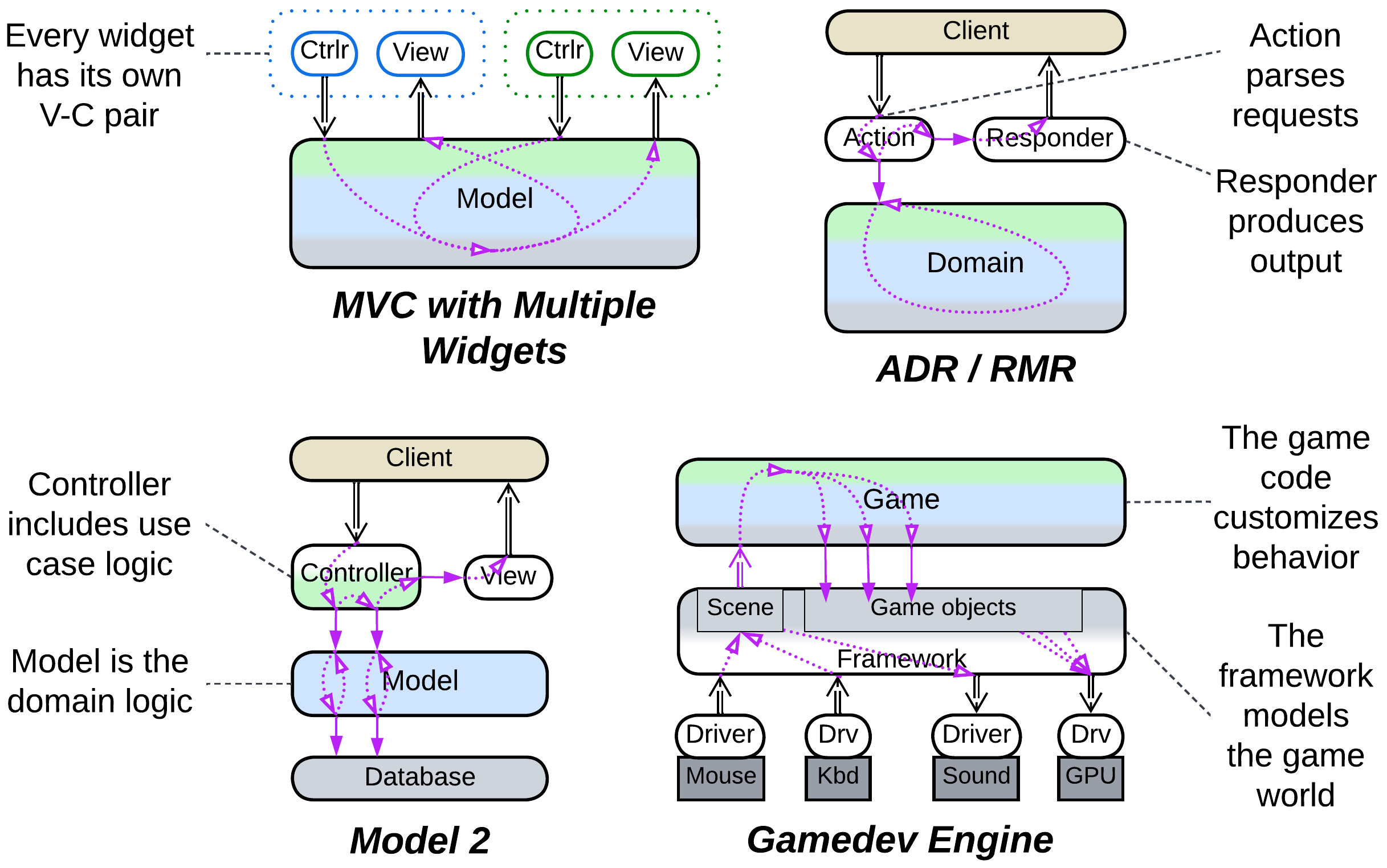

Model-View-Controller (MVC), Action-Domain-Responder (ADR), Resource-Method-Representation (RMR), Model 2 (MVC2), Game Development Engine #

When your presentation’s input and output diverge (raw mouse movement vs 3D graphics in UI, HTTP requests vs HTML pages in websites), it makes sense to separate the presentation layer into dedicated components for input and output.

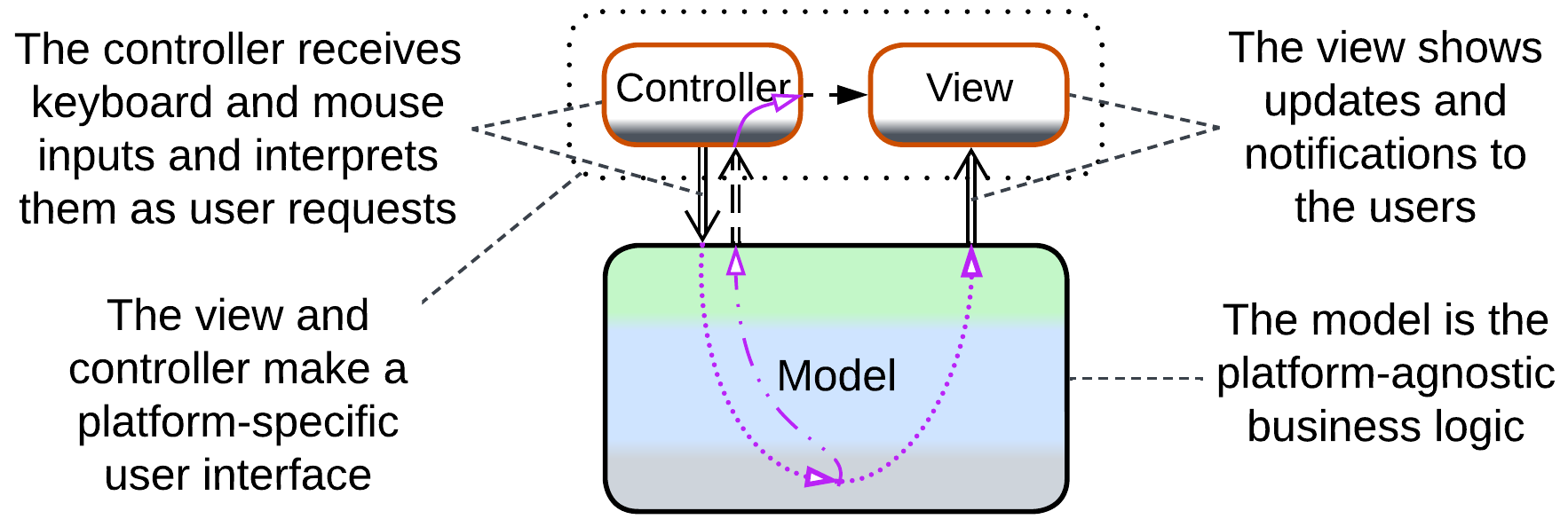

Model-View-Controller (MVC) [POSA1, POSA4] allows for cross-platform development of hand-crafted UI applications (which was necessary before universal UI frameworks emerged) by abstracting the system’s model (its main logic and data, the core of Hexagonal Architecture) from its user interface containing platform-specific controller (input) and view (output):

- The controller translates raw input into calls to the business-centric model’s API. It may also hide or lock widgets in the view when the model’s state changes.

- The model is the main UI-agnostic application which executes controller’s requests and notifies the view and, optionally, controller when its data changes.

- Upon receiving a notification, the view reads, transforms, and presents to the user the subset of the model’s data which it covers.

Each widget on the screen may have its own model-view pair. The absence of an intermediate layer between the view and model makes the view heavyweight as it has to translate the model’s data format into something presentable to users – the flaw addressed by the MVP (3-layered) patterns discussed above.

Both Action-Domain-Responder (ADR) and Resource-Method-Representation (RMR) are web layer patterns. An action (method) receives a request, calls into a domain (resource) to make changes and retrieve data and brings the results to a responder (representation) which prepares the return message or web page. ADR is technology-agnostic while RMR is HTTP-centric.

Model 2 (MVC2) is a similar pattern from the Java world with integration logic implemented in the controller.

A game development engine creates a higher-level abstraction over input from mouse / keyboard / joystick and output to sound card / GPU while more powerful engines may also model physics and character interactions. The role is quite similar to what the original MVC did, with a couple of differences:

- Games often have to deal with the low-level and very chatty interfaces of hardware components, thus the input and output are at the bottom side of the system diagram.

- The framework itself makes a cohesive layer, becoming a kind of Microkernel.

Another difference is that while MVC provides for changing target platforms by rewriting its minor components (view and controller), you are very unlikely to change your game framework – instead, it is the framework itself that makes all the platforms look identical to your code.

Summary #

Hexagonal Architecture isolates a component’s business logic from its external dependencies by inserting adapters between them. It protects from vendor lock-in and allows for late changes of third-party components but requires all the APIs to be designed before programming can start and often hinders performance optimizations.