Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) #

The whole is equal to the sum of the parts. Distributed Object-Oriented Design.

Known as: Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA), Segmented Architecture.

Variants:

- Distributed Monolith,

- Enterprise SOA,

- Domain-Oriented Microservice Architecture (DOMA),

- (misapplied) Automotive SOA,

- Nanoservices.

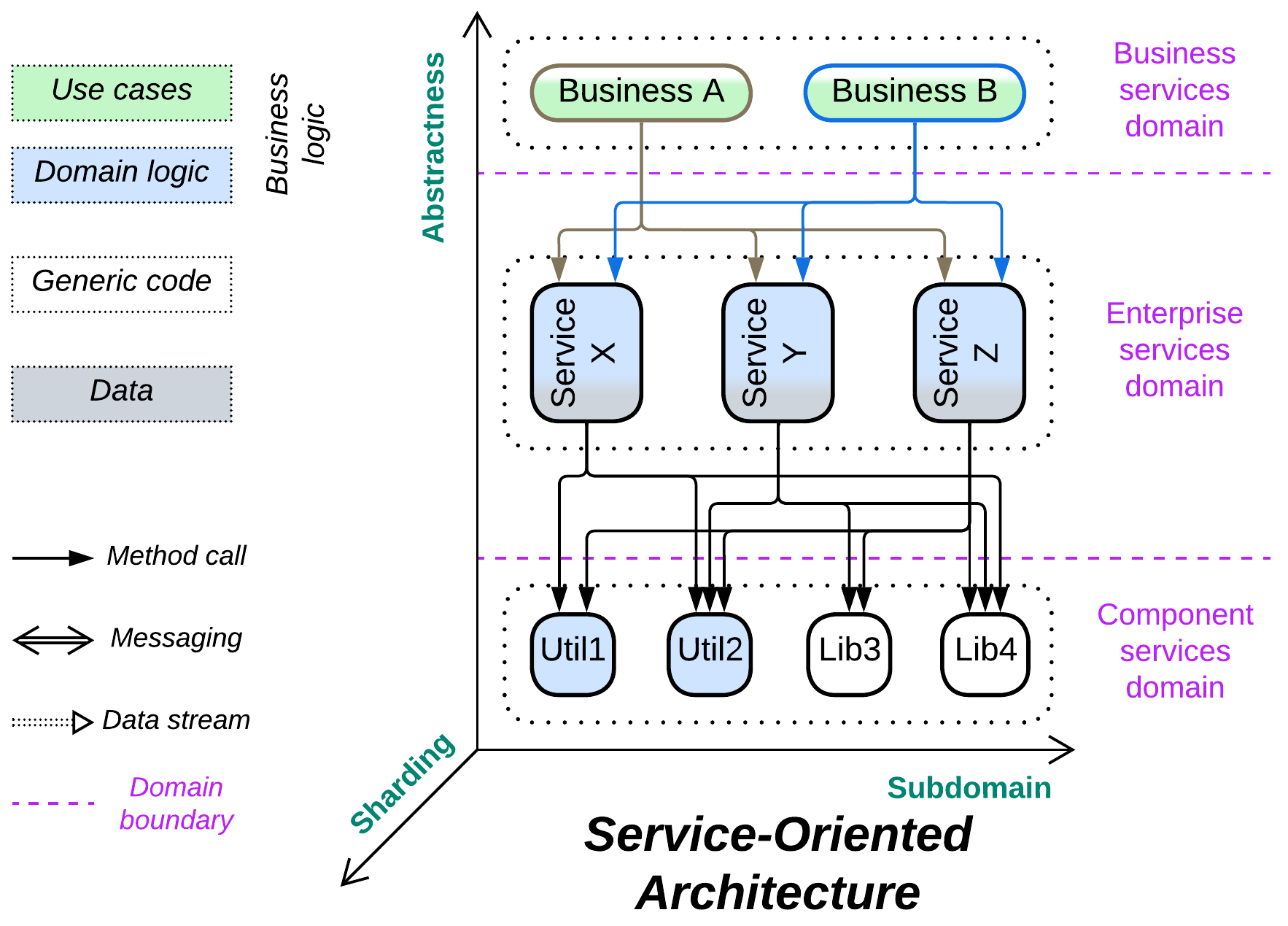

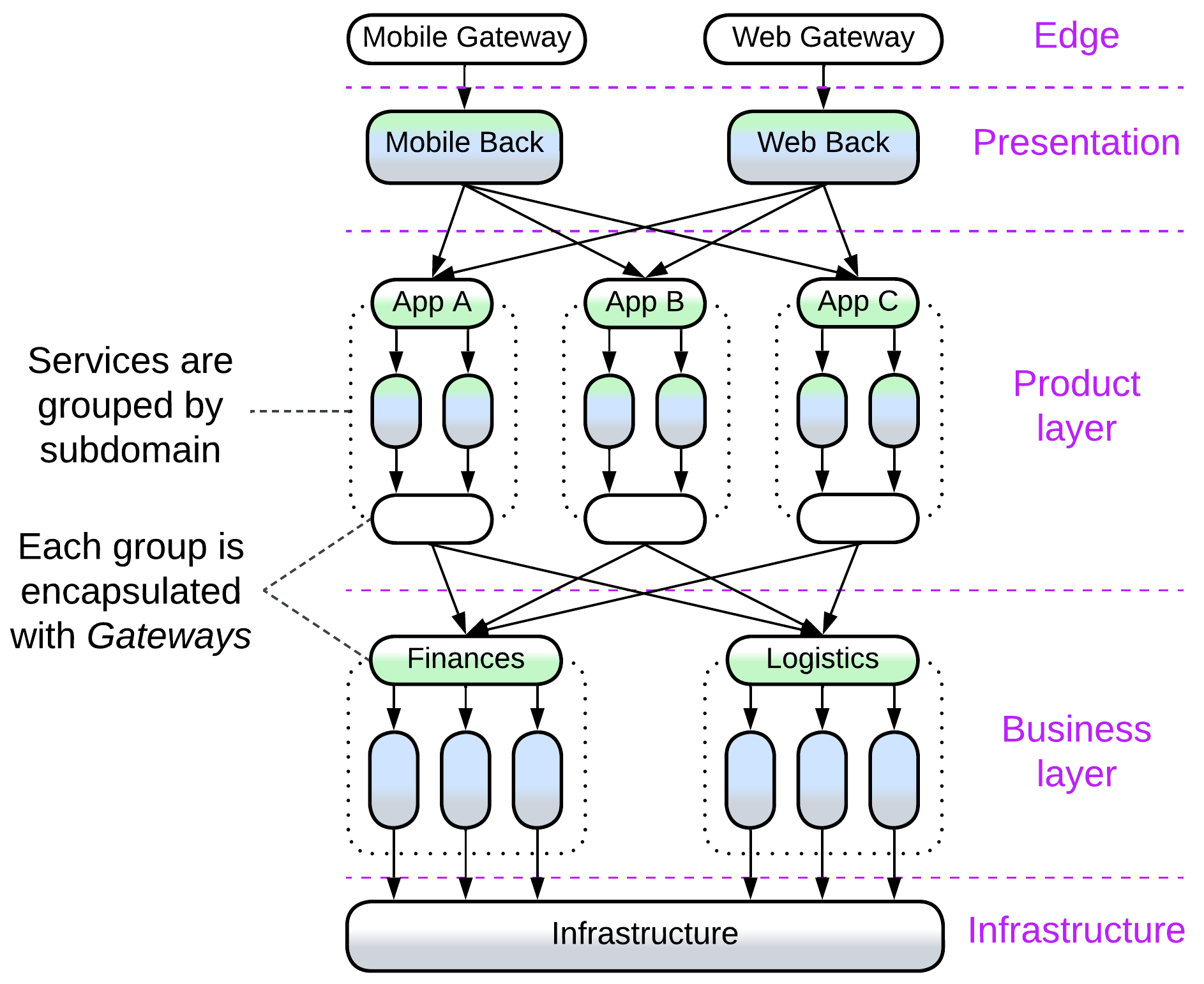

Structure: Usually three layers of services where each service can access any other service in its own or lower layers.

Type: Main, derived from Layers.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Supports huge codebases | Very hard to debug |

| Multiple development teams and technologies | Hard to test as there are many dependencies |

| Forces may vary between the components | Very poor latency |

| Deployment to dedicated hardware | Very high DevOps complexity |

| Fine-grained scaling | The teams are highly interdependent |

References: [FSA] has a chapter on Orchestration-Driven (Enterprise) Service-Oriented Architecture. [MP] mentions Distributed Monolith. There is also much (though somewhat conflicting) content over the Web.

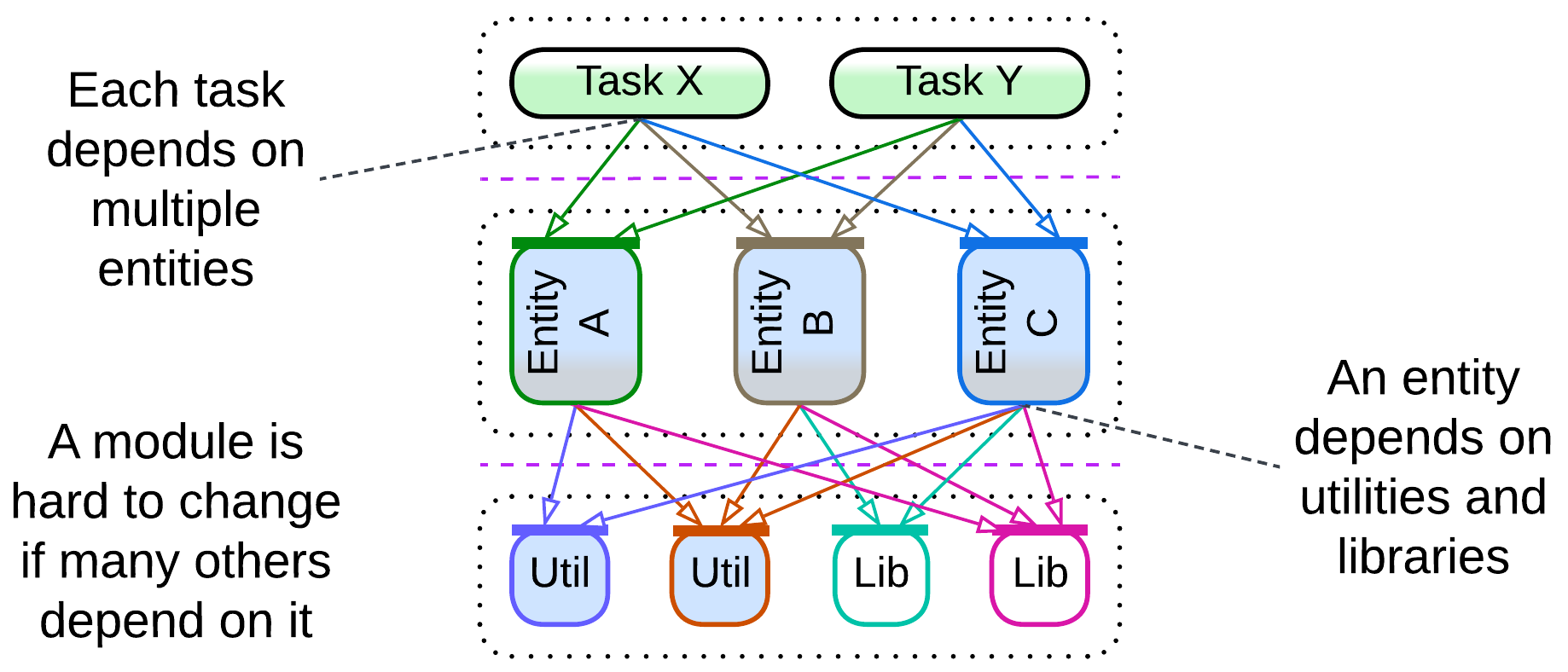

Service-Oriented Architecture looks like the application of modular or object-oriented design followed by distribution of the resulting components over a network. The system usually contains three (rarely four) layers of services where every service has access to all the services below it (and sometimes some within its own layer). The services stay small, but as their number grows it becomes hard to keep in mind all the API methods and contracts available which a high-level component might use. Another issue originates from the idea of reusable components – multiple applications, written for different clients with varied workflows, require the same service to behave in (subtly) different ways, either causing its API to bloat or else impairing its usability (which means that a new customized duplicate service will likely be added to the system). Use cases are slow because there is much interservice communication over the network. Teams are interdependent as any use case involves many services, each owned by a different team. Testability is poor because there are too many moving (and being independently updated!) parts. The foundational idea of service reuse failed in practice, but its child architecture, SOA, still survives in historical environments.

Even though SOA fell from grace and is rarely seen in modern projects, it may soon be resurrected by low-code and no-code frameworks for serverless systems (e.g. Nanoservices) – it has everything ready: code reuse, granular deployment, and elastic scaling.

Performance #

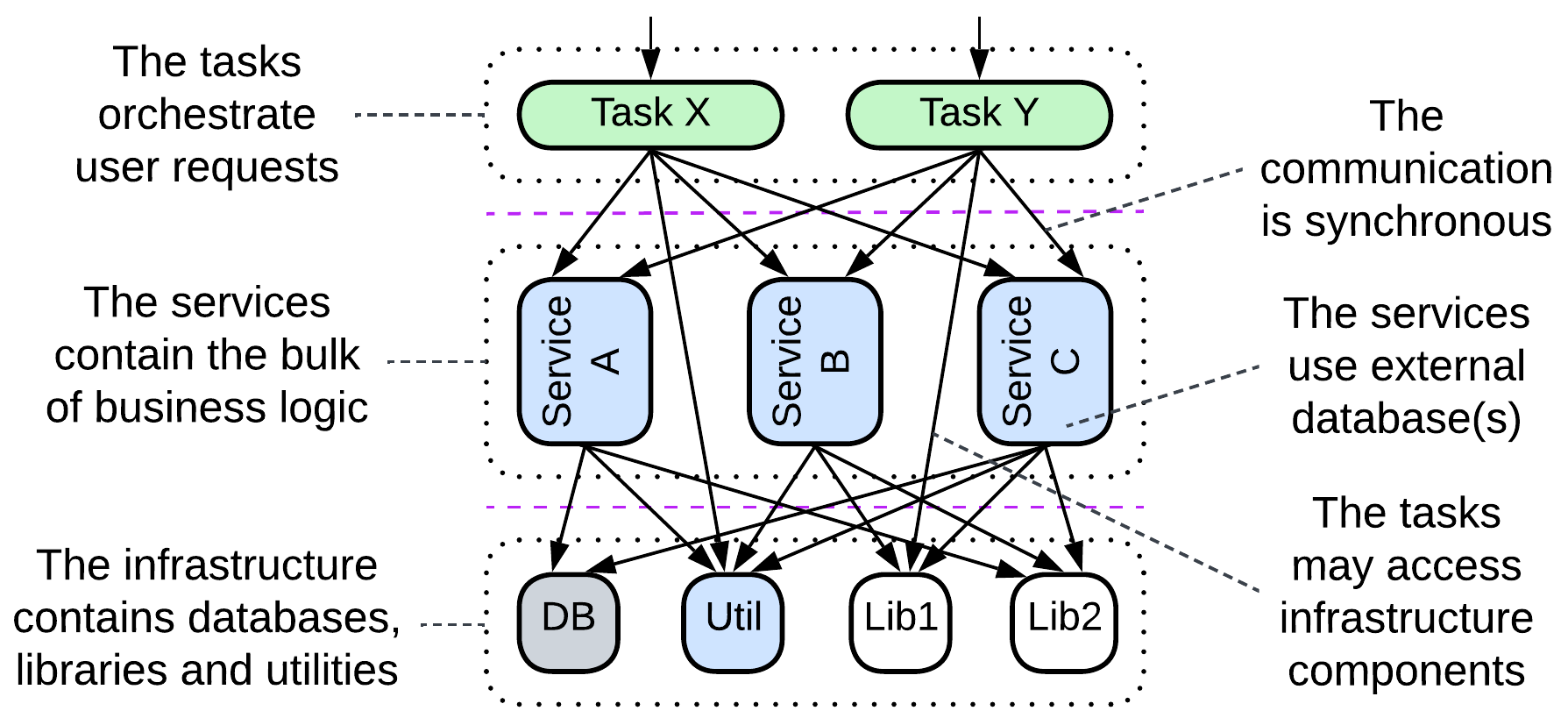

SOA is remarkable for its poor latency which results from extensive communication between its distributed components. There is hardly any way to help that as processing a request usually involves many services from all the layers.

Nevertheless, the pattern allows for good throughput as its stateless components can be scaled individually, leaving the system’s scalability to be limited only by its databases, Middleware … and funding.

Dependencies #

Each service of each layer depends on everything it uses. As a result, development of a low-level (utility) component may be paralyzed because too many services already use it, thus no changes are welcome. Hence, the team writes a new version of their utility as a new service, which defeats the very idea of component reuse that SOA was based on.

Applicability #

Service-Oriented Architecture is useful in:

- Huge projects. Many teams can be employed, each handling a moderate amount of code. However, dependencies between the teams and the combined length of the APIs in the system may stall the development anyway.

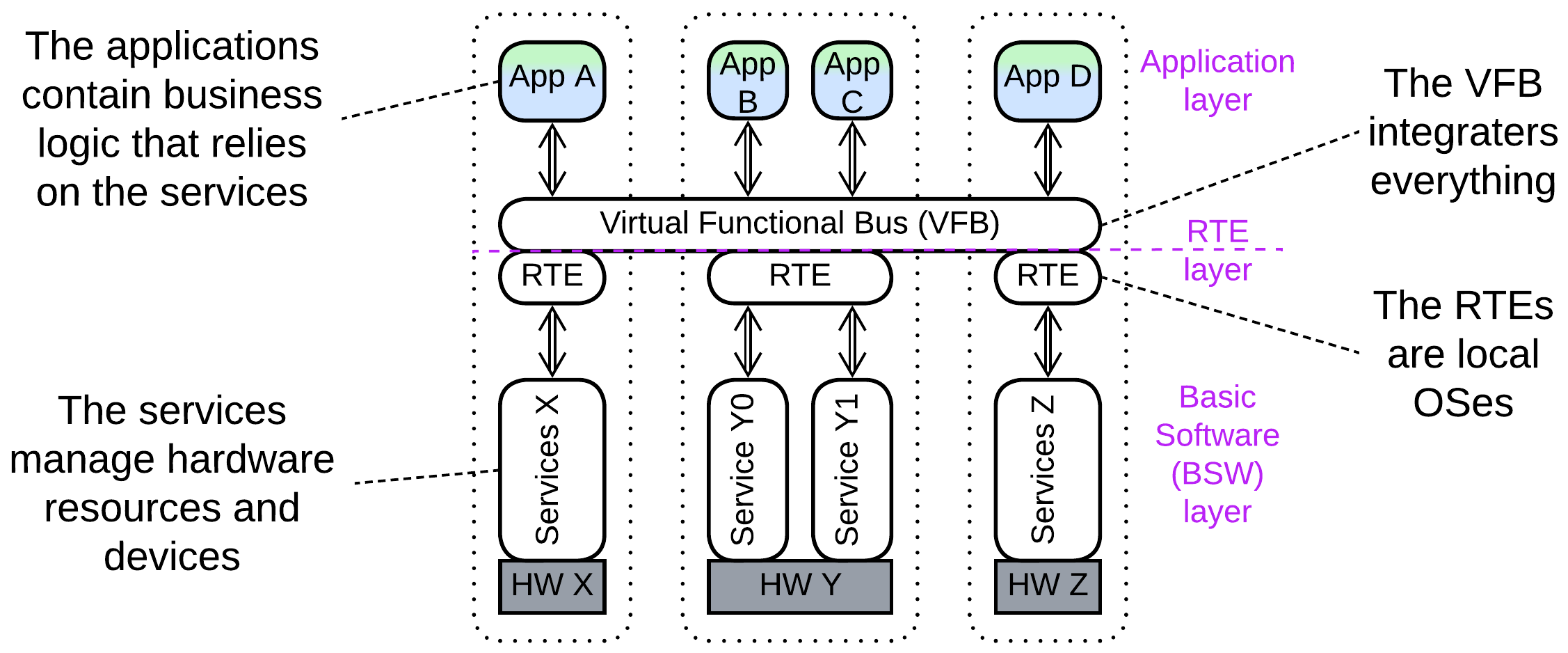

- A system of specialized hardware devices. If there is a lot of different hardware interacting in complex ways, the system may naturally fit the description of SOA. Don’t fight this kind of Conway’s law.

Service-Oriented Architecture hurts:

- Fast-paced projects. Any feature requires coordination of multiple teams, which is hard to achieve in practice.

- Latency-sensitive domains. Over-distribution means too much messaging causing too high latency.

- High availability systems. Components may fail. A failure of a lower-level component is going to stall a large part of the system because every low-level component is used by many higher-level services.

- Safety-critical systems with frequent updates. SOA is hard to test comprehensively. Either all the components must be certified with a strict standard and an exhaustive test suite or any single component update requires re-testing the entire system.

Relations #

Service-Oriented Architecture:

- Is a stack of Layers each of which is divided into Services.

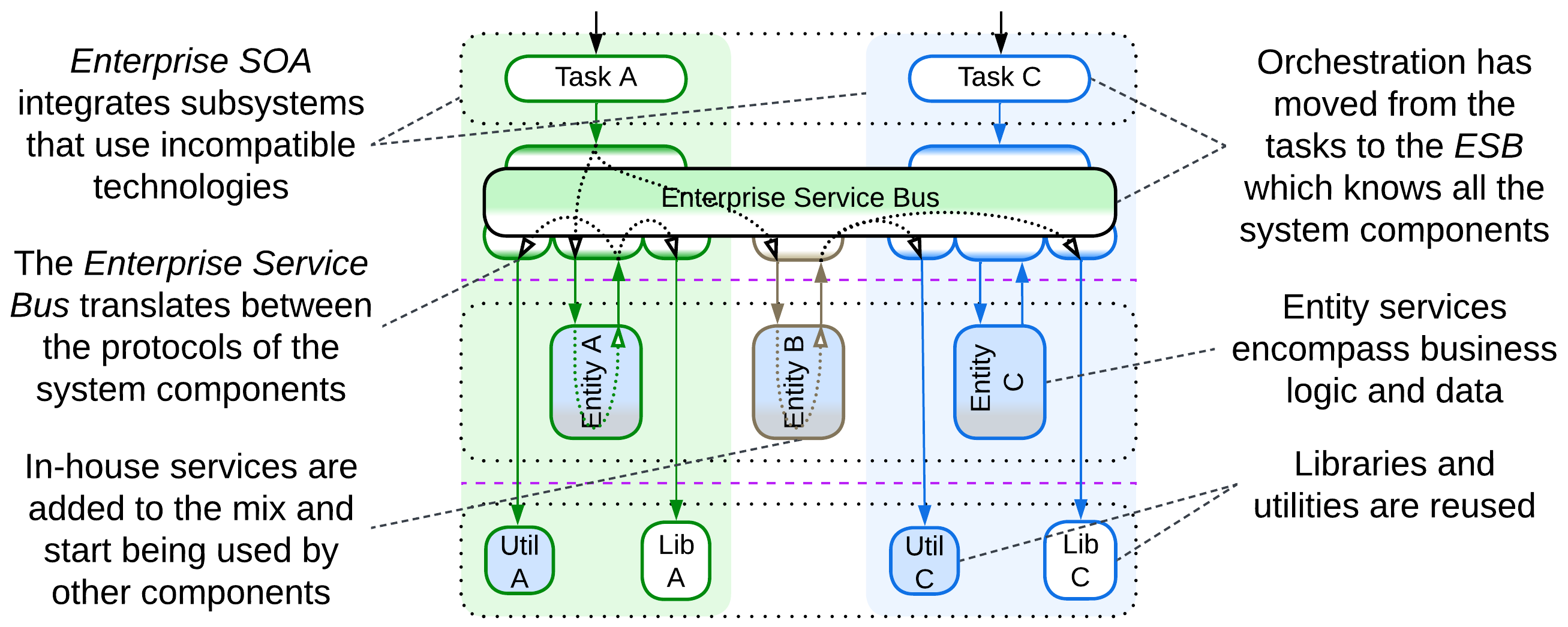

- Is often extended with an Enterprise Service Bus (a kind of orchestrating Middleware) and one or more Shared Databases.

Variants #

This architecture was hyped at the time when enterprises were expanding by acquiring smaller companies and conjoining their IT systems. The resulting merged systems were still heterogeneous and the development experience unpleasant, which inclined popular opinion towards the then novel notion of Microservices. As nearly everybody has turned from merging existing systems to failing to apply Microservices in practice, the chance to find a pure greenfield SOA project in the wild is quite low. Many systems which are marketed as SOA are strongly modified:

Distributed Monolith #

If a Monolith gets too complex and resource-hungry, the most simple & stupid way out of the trouble is to deploy each of its component modules to separate, dedicated hardware. The resulting services still communicate synchronously and are subject to domino effect on failure. Such an architecture may be seen as a (hopefully) intermediate structure in transition to more independent and stable event-driven Services (or Cells).

Enterprise SOA #

Multiple systems of Services, each featuring an API Gateway and sometimes a Shared Database, are integrated, resulting in new cross-connections. Much of the orchestration logic is removed from the API Gateways and reimplemented in an orchestrating Middleware called Enterprise Service Bus (ESB). This option allows for fast and only moderately intrusive integration (as no changes to the services, which implement the mass of the business logic, are required), but the single orchestrating component (ESB) often becomes the bottleneck for future development of the system due to its size and complexity. It is likely that if the orchestration were encapsulated in the individual API Gateways, the system would be easier to deal with (making what is now marketed by WSO2 as Cell-Based Architecture).

The layers of SOA are:

- Business Process (Task) – the definitions of use cases for a single business department, similar to the API Gateways layer of BFF.

- Services (Enterprise, Entity) – the implementation of the business logic of a subdomain, to be used by the tasks.

- Components (Application & Infrastructure, Utility) – external libraries and in-house utilities that are designed for shared use by the services layer.

Domain-Oriented Microservice Architecture (DOMA) #

A huge business may build SOA of Cells (called Domains) instead of plain Services. That greatly simplifies:

- administration (by reducing the number of components at the system level – Uber packed 2200 Microservices into 70 Domains),

- refactoring of individual subsystems (which are isolated behind Cell Gateways),

- development of business logic (as programmers need to learn much fewer interfaces of components they rely on).

Uber’s DOMA also makes heavy use of Plugins which programmers from a client service team develop for the services they rely on. That allows for cross-Domain customization (injection of business logic from another Cell) of a service’s behavior without making (slow) interservice calls.

(misapplied) Automotive SOA #

Automotive architectures are marketed as SOA, but the old AUTOSAR Classic looks more like Microkernel (which indeed is similar to a 2-layered SOA with an ESB) while the newer system diagrams resemble a Hierarchy. Therefore, they are addressed in the corresponding chapters.

Nanoservices #

It seems that some proponents of Nanoservices take them for a novel version of SOA – with the old good promise of reusable components. However, as that promise was failing miserably ever since the ancient days of OOP, it is no surprise that in practice Nanoservices are used instead to build Pipelines with little to no reuse.

Evolutions #

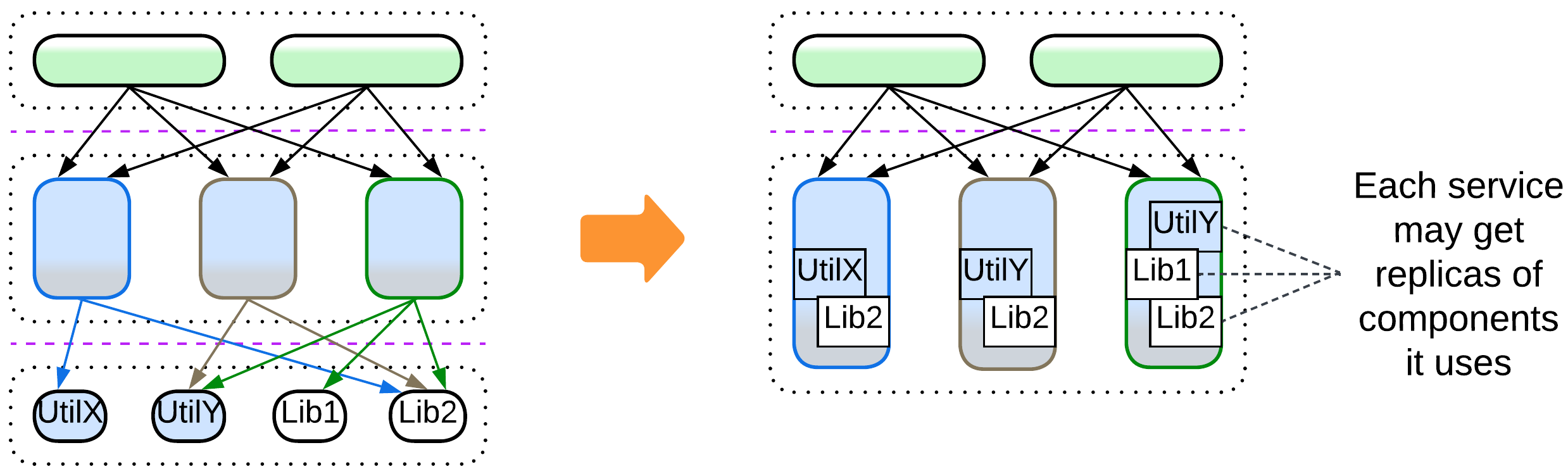

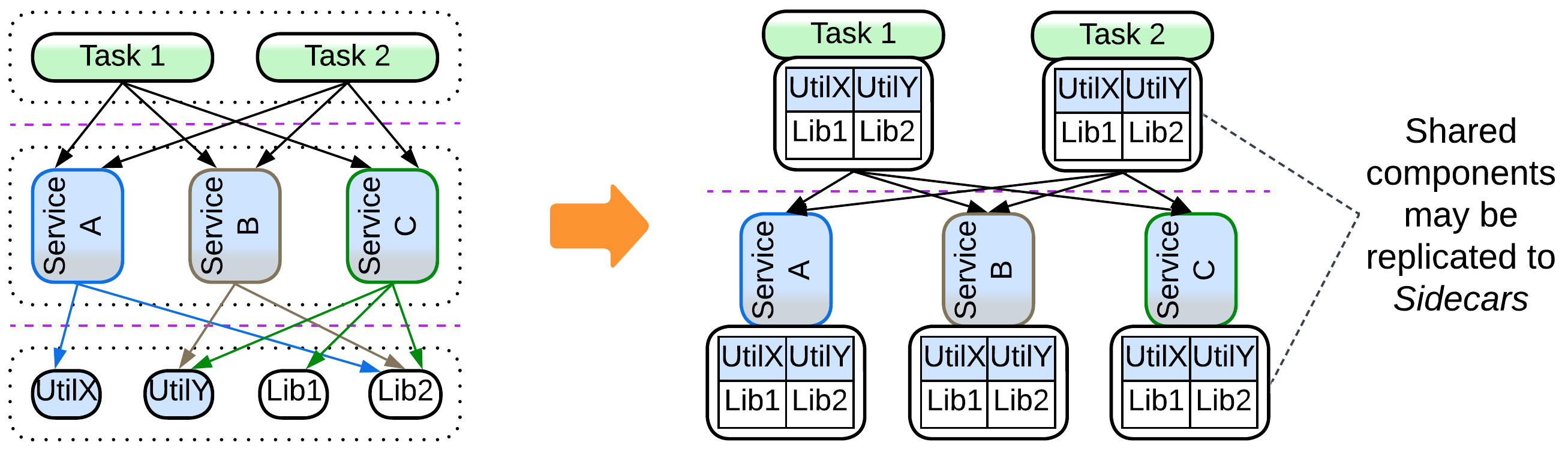

SOA suffers from excessive reuse and fragmentation. To fix that, first and foremost, each service of the components (utility) layer should be duplicated:

- Into every service that uses it, giving the developers who write the business logic full control of all the code that they use. Now they have several projects to support on their own (instead of asking other teams to make changes to their components).

- Or into Sidecars [DDS] if you employ a Service Mesh, resulting in much fewer network hops (thus lower latency) in request processing, but retaining the inter-team dependencies.

That removes the largest and most obvious part of the fragmentation, making the ESB (if you use one) orchestrate only the entity layer.

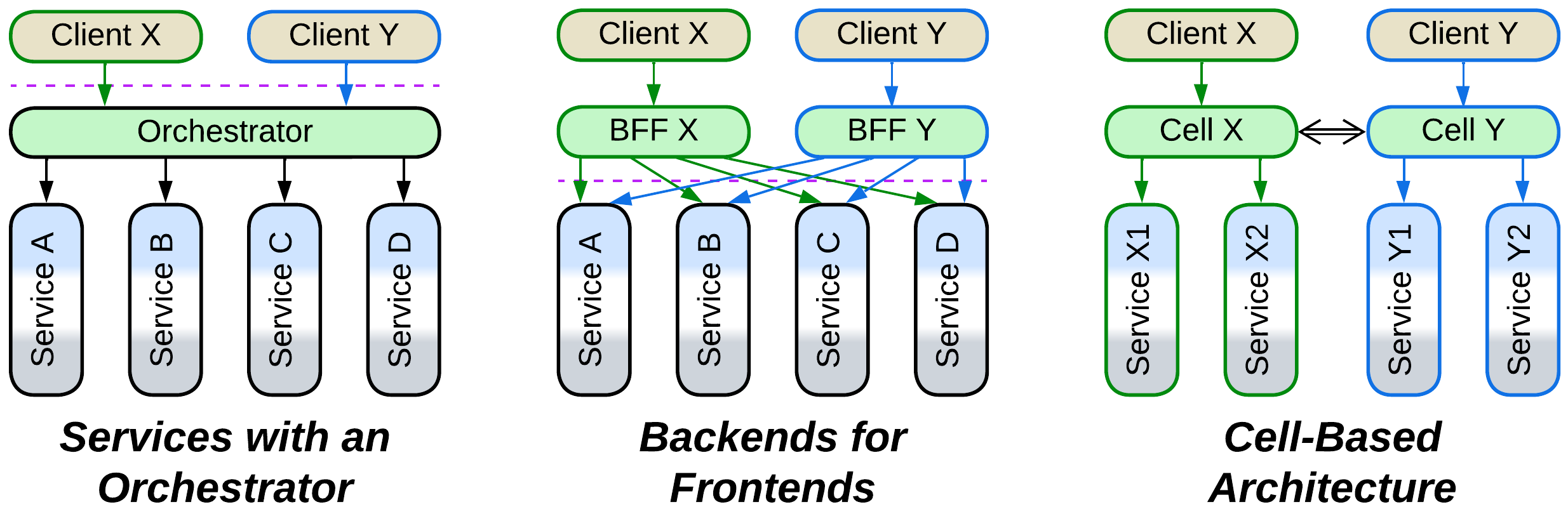

Afterwards you may deal with the remaining orchestration. The idea is to move the orchestration logic from the ESB to an explicit layer of Orchestrators:

- Either a monolithic Orchestrator over all the services.

- Or Backends for Frontends with an Orchestrator per client type (department of an enterprise) if each client uses most of the services.

- Or go for Cells with an Orchestrator per subdomain if your clients are subdomain-bound.

- Or a combination of the above.

Still another step is unbundling the Middleware, which supports multiple protocols via Adapters:

- If you have a Service Mesh, an Adapter may be put to a Sidecar [DDS].

- Otherwise there is an option of a hierarchical Middleware (Bus of Buses) if closely related components share protocols.

Still, the evolution of Middleware may not bring any real benefit except for removing the ESB altogether, which may not be that bad after all when it is not misused.

In any case, many of the evolutions will likely be very expensive, thus it makes sense to conduct some of them gradually via a kind of strangler fig approach. Or let the architecture live and die as it is.

Summary #

Service-Oriented Architecture divides each of the integration, domain, and utility layers into shared services. The extensive fragmentation and reuse degrade performance and speed of development. Nevertheless, huge projects are known to survive with this architecture.