Shared Repository #

Knowledge itself is power. Sharing data is simple (& stupid).

Known as: Shared Repository [POSA4].

Aspects:

- Data storage,

- Data consistency,

- Data change notifications.

Variants:

- Shared Database [EIP] / Integration Database / Data Domain [SAHP] / Database of Service-Based Architecture [FSA],

- Blackboard [POSA1, POSA4],

- Data Grid of Space-Based Architecture [SAP, FSA] / Replicated Cache [SAHP] / Distributed Cache,

- Shared Memory,

- Shared File System,

- (with a Middleware) Persistent Event Log / Shared Event Store,

- (inexact) Stamp Coupling [SAHP].

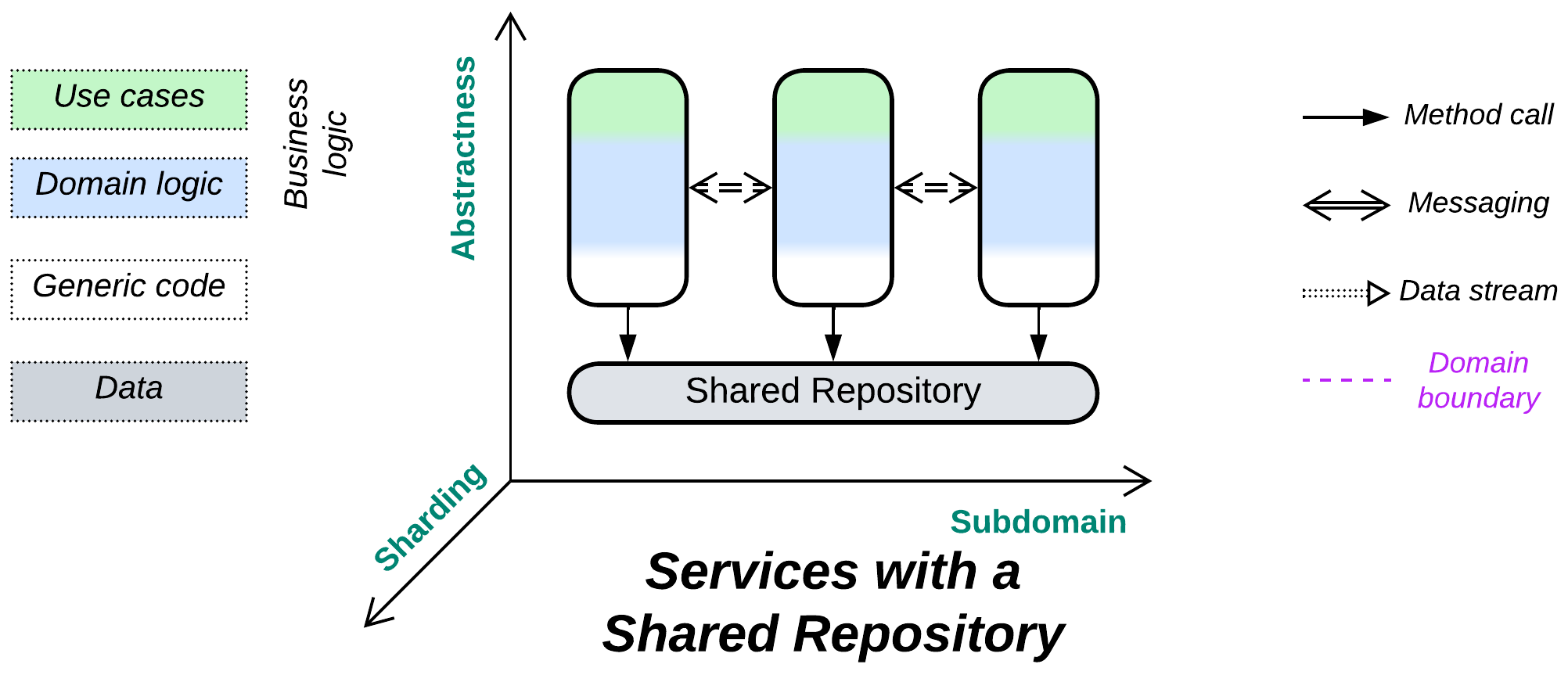

Structure: A layer of data shared among higher-level components.

Type: Extension for Services or Shards.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Supports domains with coupled data | A single point of failure |

| Implements data access and synchronization (consistency) concerns | All the services depend on the schema of the shared data |

| Helps saving on hardware, licenses, traffic, and administration | A single database technology may not fit the needs of all the services equally well |

| Quick start for a project | Limits scalability |

References: [DDIA] is all about databases; [FSA] has chapters on Service-Based Architecture and Space-Based Architecture; [DEDS] deals with Shared Event Store.

A Shared Repository builds communication in the system around its data, which is natural for data-centric domains and multiple instances of a stateless service and may often simplify development of a system of Services that need to exchange data. It covers the following concerns:

- Storage of the entire domain data.

- Keeping the data self-consistent by providing atomic transactions for use by the application code.

- Communication between the services (if the repository supports notifications on data change).

The drawbacks are extensive coupling (it’s hard to alter a thing which is used in many places throughout the entire system) and limited scalability (even distributed databases struggle against distributed locks and the need to keep their nodes’ data in sync).

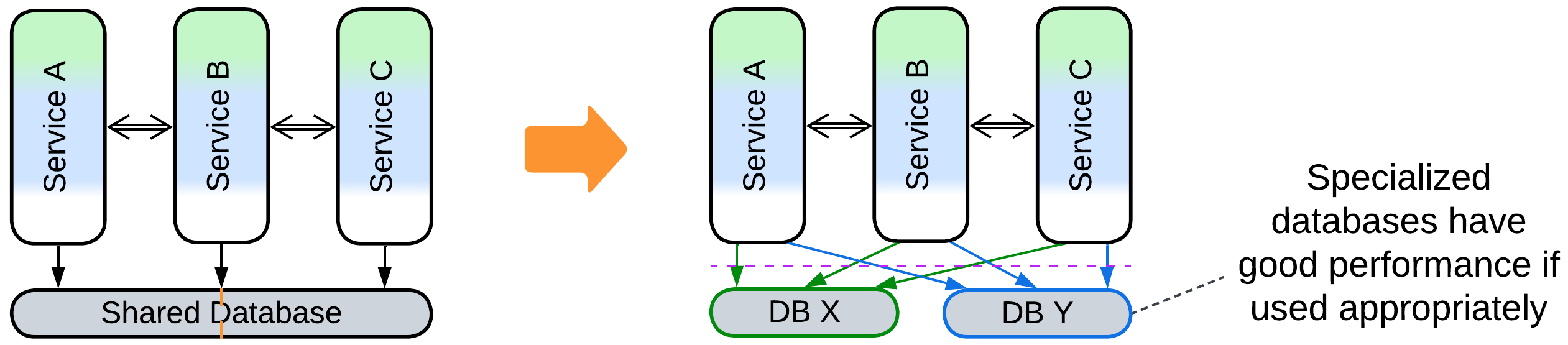

Performance #

A shared database with consistency guarantees (ACID) is likely to lower the total resource consumption compared to one database per service (as the services don’t need to implement and keep updated CQRS views [DDIA, MP] of other services’ data) but it increases latency and it may become the system’s performance bottleneck. Moreover, by using a shared database services lose the ability to choose the database technologies which best fit their tasks and data.

Another danger lies with locking records inside the database. Different services may use different order of tables in transactions, hitting deadlocks in the database engine which show up as transaction timeouts.

Non-transactional distributed databases may be very fast when colocated with the services (see Space-Based Architecture) but the resource consumption becomes very high because of the associated data duplication (as every instance of each service gets a copy of the entire dataset) and simultaneous writes may corrupt the data (cause inconsistencies or merge conflicts).

Dependencies #

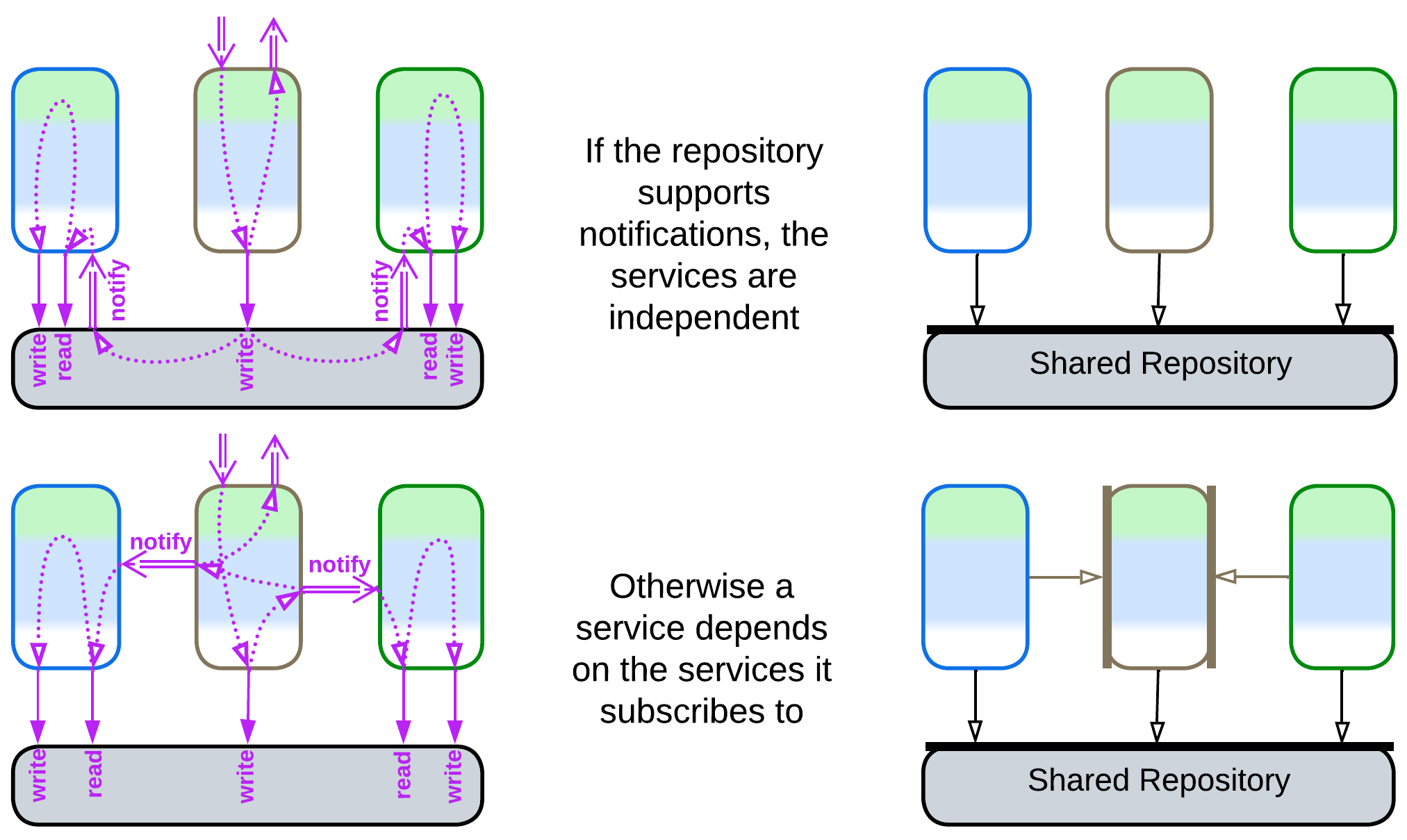

Normally, every service depends on the repository. If the repository does not provide notifications on changes to the data, the services may need to communicate directly, in which case they will also depend on each other through choreography or mutual orchestration.

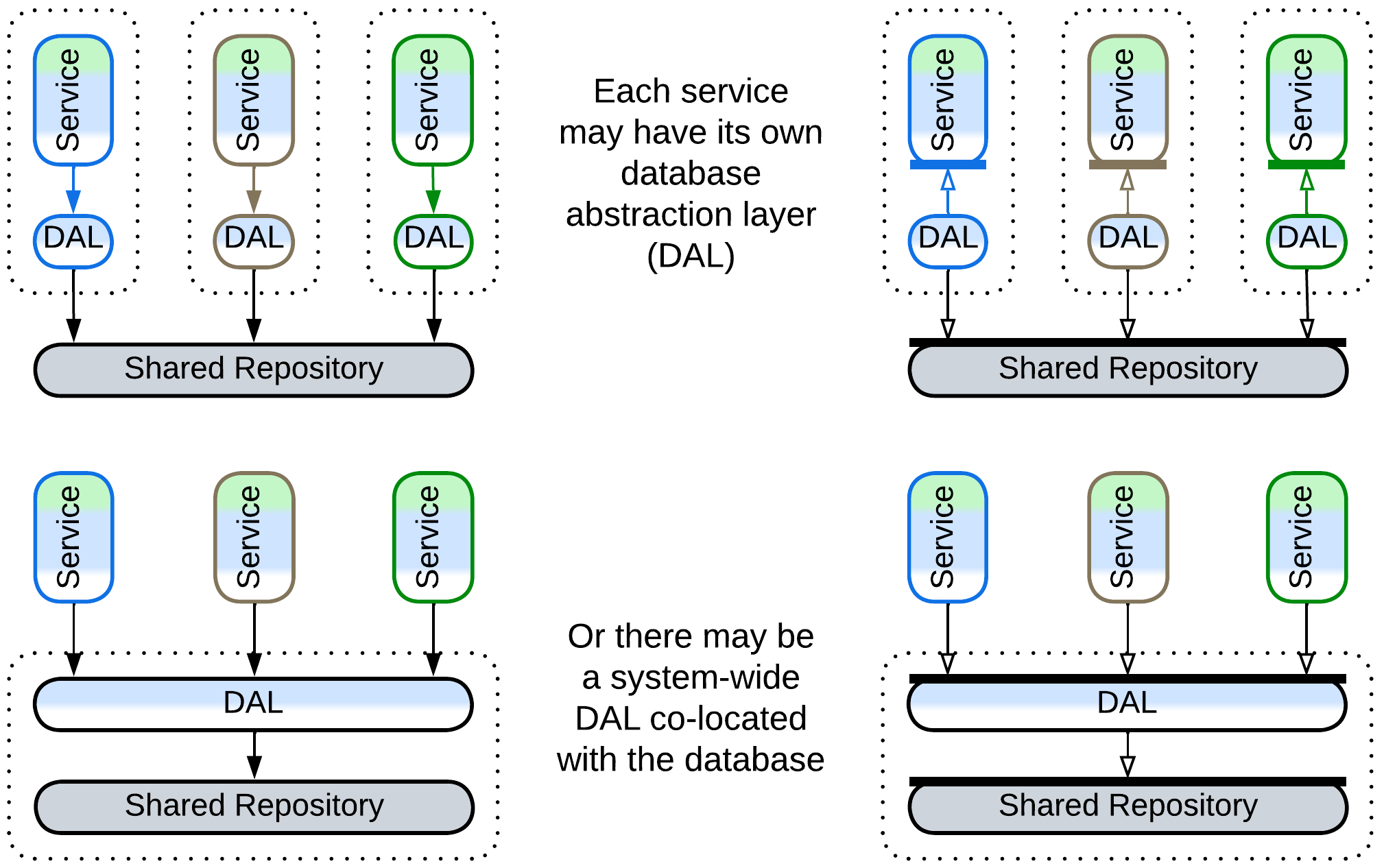

The dependency on repository technology and a data schema is dangerous for long-running projects as both of them may need to change sooner or later. Decoupling the code from the data storage is done with yet another layer of indirection which is called a Database Abstraction Layer (DAL), a Database Access Layer [POSA4], or a Data Mapper [PEAA]. The DAL, which translates between the data schema and database’s API on one side and the business logic’s SPI on the other side, may reside inside each service or wrap the database:

Still, the DAL does not remove shared dependencies and only adds some flexibility. It seems that there is a peculiar kind of coupling through shared components: if one of the services needs to change the database schema or technology to better suit its needs, it is unable to do so because other components rely on (and exploit) the old schema and technology. Even deploying a second database, private to the service, is often not an option, as there is no convenient way to keep the databases in sync.

Applicability #

Shared Repository is good for:

- Data-centric domains. If most of your domain’s data is used in every subdomain, keeping any part of it private to a single service will be a pain in the system design. Examples include a ticket reservation system and even the minesweeper game.

- A scalable service. When you run several instances of a service, like in Microservices, the instances are likely to be identical and stateless, with the service’s data pushed out to a database shared among the instances.

- Huge datasets. Sometimes you may need to deal with a lot of data. It is unwise (meaning expensive) to stream and replicate it between your services just for the sake of ensuring their isolation. Share it instead. If the data does not fit in an ordinary database, some kind of Space-Based Architecture (which was invented to this end) may become your friend.

- Quick simple projects. Don’t over-engineer if the project won’t live long enough to benefit from its flexibility. You may also save a buck or two on the storage.

Shared Repository is bad for:

- Quickly evolving, complex projects. As everything changes, you just cannot devise a stable schema, while every change of the database schema breaks all the services.

- Varied forces and algorithms. Different services may require different kinds of databases to work efficiently.

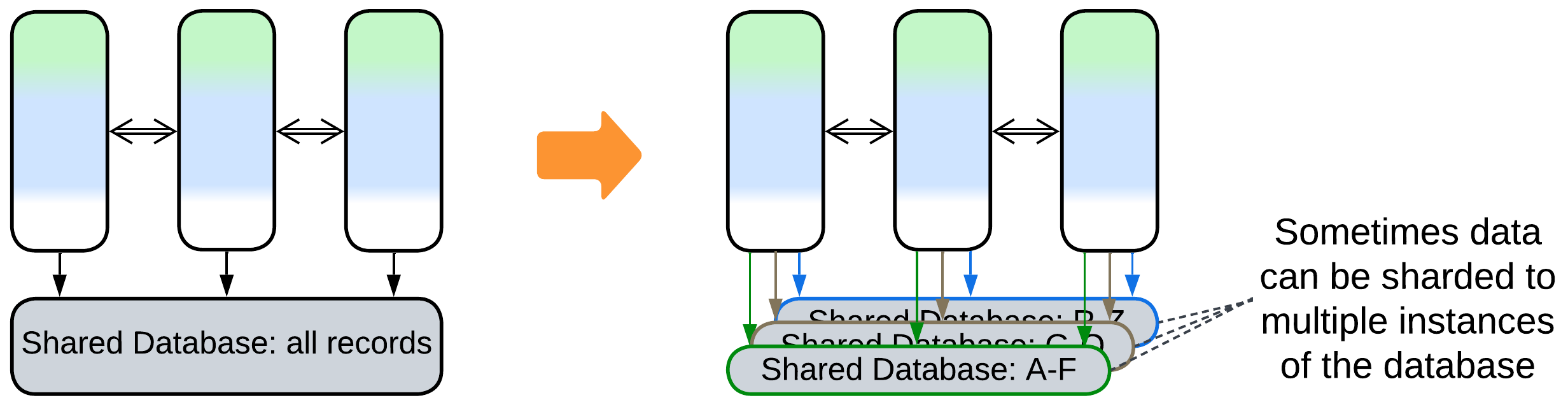

- Big data with random writes. Your data does not fit on a single server. If you want to avoid write conflicts, you must keep all the database nodes synchronized, which kills performance. If you let them all broadcast their changes asynchronously, you get collisions. You may want to first decouple and shard the data as much as possible, and then turn your attention to esoteric databases, specialized caches, and even tailor-made Middleware to get out of the trouble.

Relations #

Shared Repository:

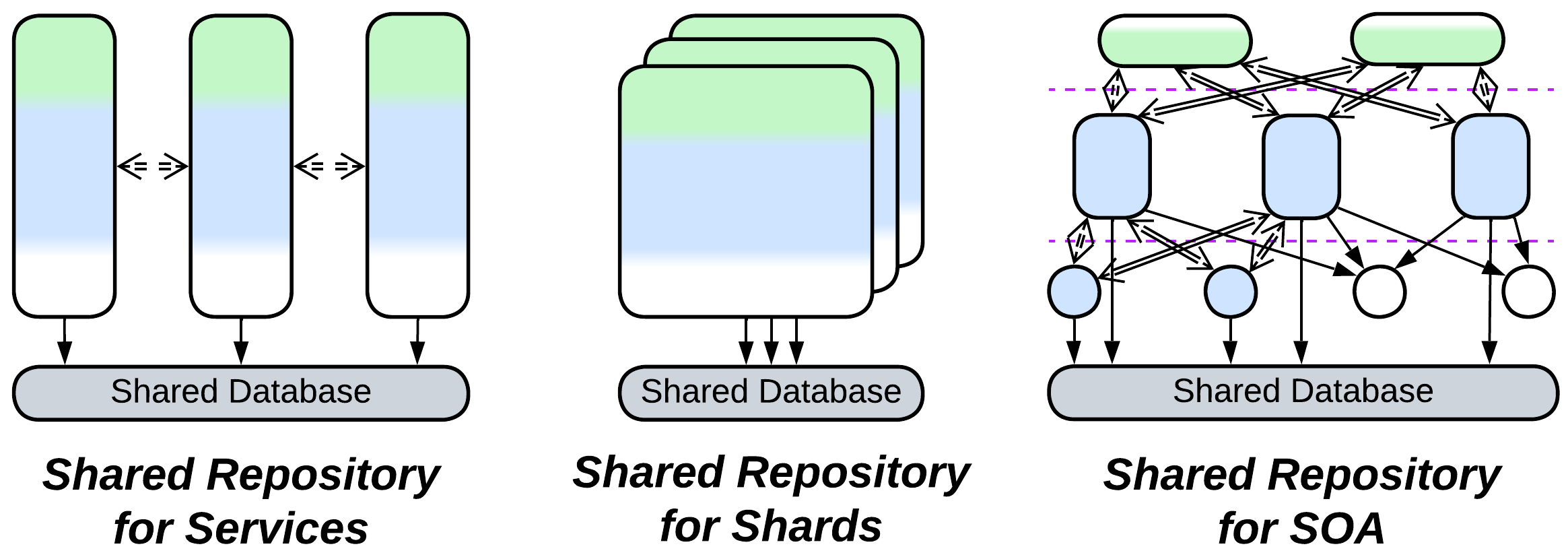

- Extends Services, Service-Oriented Architecture, Shards, or occasionally Layers.

- Is a part of a persistent Middleware or Nanoservices.

- Is closely related to Middleware.

- May be implemented by a Mesh.

Variants #

Shared Repository is a sibling of Middleware. While a Middleware assists direct communication between services (shared-nothing messaging), a Shared Repository grants them indirect communication through access to an external state (similar to shared memory) which usually stores all the data for the domain.

A Shared Repository may provide a generic interface (e.g. SQL) or a custom API (with a domain-aware Adapter / ORM for the database). The repository can be anything ranging from a trivial OS file system or a memory block accessible from all the components to an ordinary database to a Mesh-based, distributed tuple space:

Shared Database, Integration Database, Data Domain, Database of Service-Based Architecture #

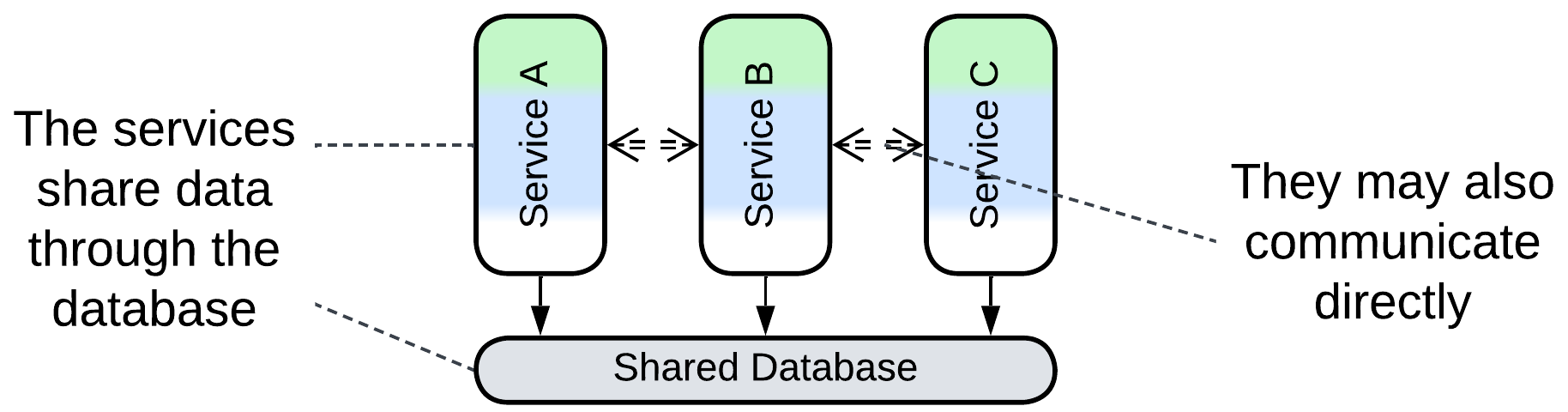

Shared Database [EIP], Integration Database, or Data Domain [SAHP] is a single database available to several services. The services may subscribe to data change triggers in the database itself or notify each other directly about domain events. The latter is often the case with Service-Based Architecture [FSA] which consists of large services dedicated to subdomains.

Blackboard #

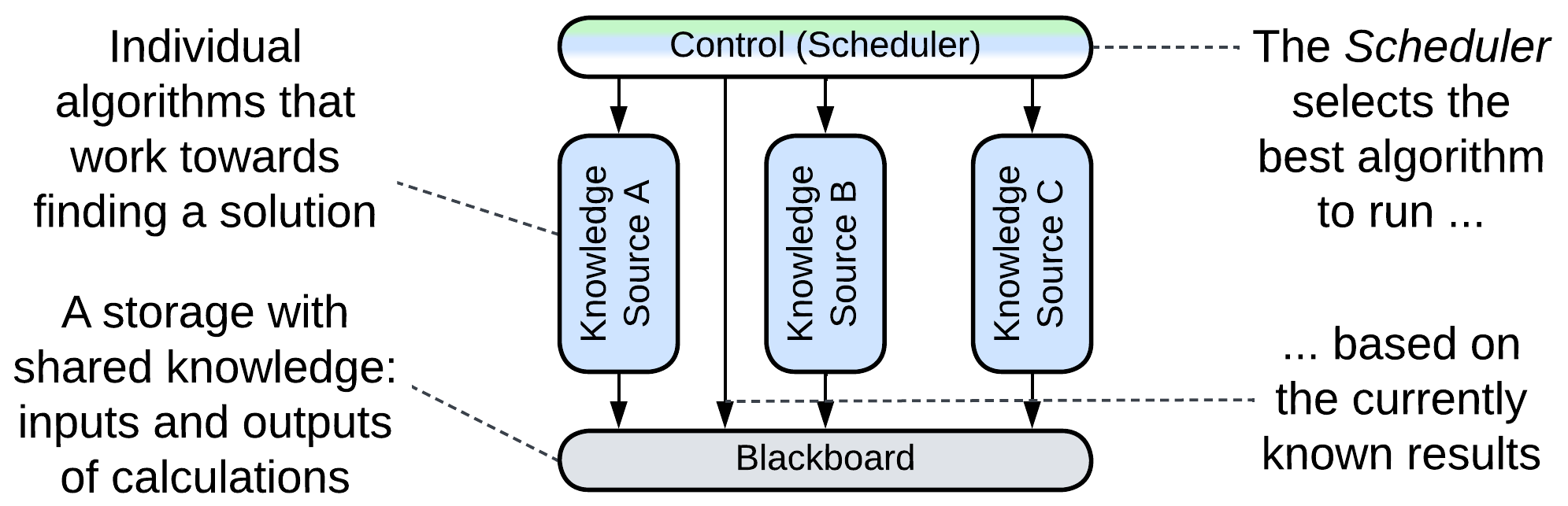

Blackboard [POSA1, POSA4] was used for non-deterministic calculations where several algorithms were concurring and collaborating to gradually build a solution from incomplete inputs. The control (Orchestrator) component schedules the work of several knowledge sources (Services) which encapsulate algorithms for processing the data stored in the blackboard (Shared Repository). This approach has likely been superseded by convolutional neural networks.

Examples: several use cases are mentioned on Wikipedia.

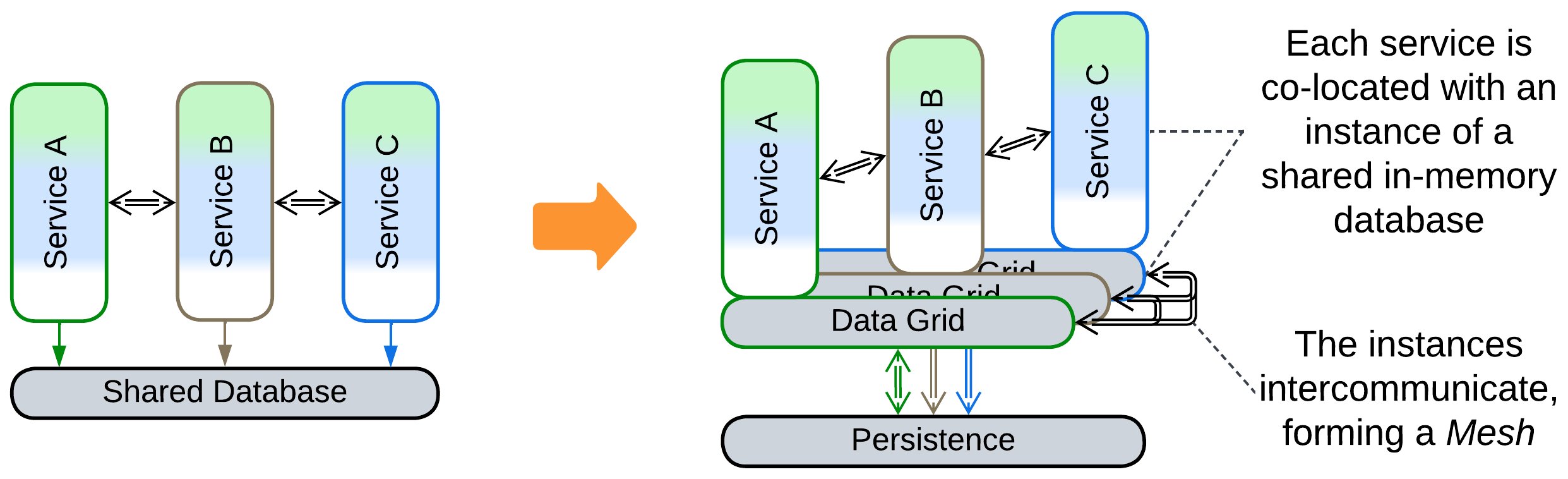

Data Grid of Space-Based Architecture (SBA), Replicated Cache, Distributed Cache #

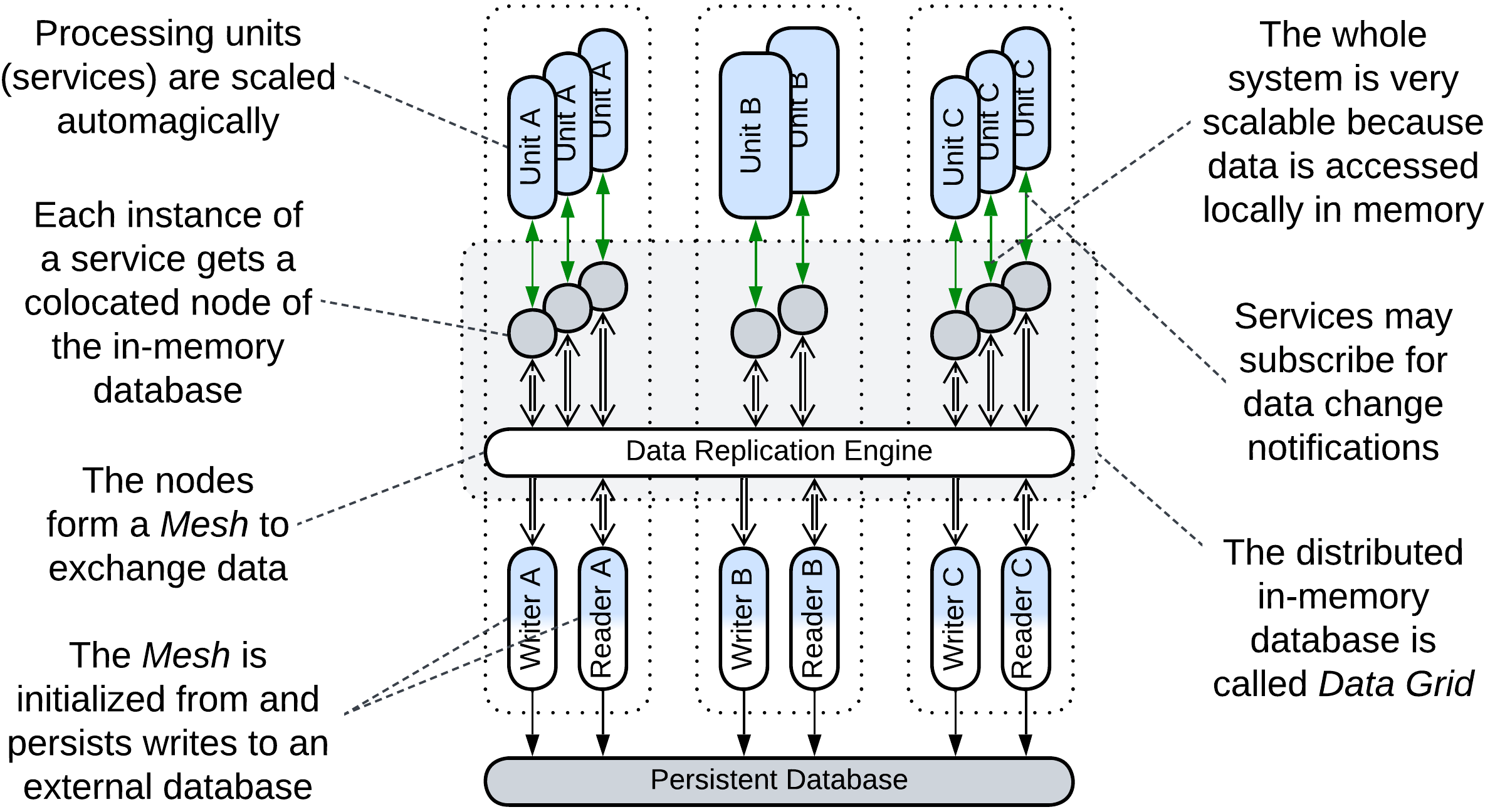

The Space-Based Architecture (SBA) [SAP, FSA] is a Service Mesh (a Mesh-based Middleware with at least one Proxy per service instance) which also implements an in-memory tuple space (shared dictionary). Although it does not provide a full-featured database interface it has very good performance, elasticity, and fault tolerance, while some implementations allow for dealing with datasets which are much larger than anything digestible by ordinary databases. Its drawbacks include write collisions and high operating costs (huge traffic for data replication and lots of RAM to store the replicas).

The main components of the architecture are:

- Processing Units – the Services with the business logic. There may be one class of Processing Units, making SBA look like Pool (Shards), or multiple classes, in which case the architecture becomes similar to Microservices with a Shared Database.

- Data Grid (Replicated Cache [SAHP]) – a Mesh-based in-memory database. Each node of the Data Grid is co-located with a single instance of a Processing Unit, providing the latter with very fast access to the data. Changes to the data are replicated across the grid by its virtual Data Replication Engine which is usually implemented by every node of the grid.

- Persistent Database – an external database which the Data Grid replicates (caches). Its schema is encapsulated in the Readers and Writers.

- Data Readers – components that read any data unavailable in the Data Grid from the Persistent Database. Most cases see Readers employed upon starting the system to upload the entire contents of the database into the memory of the nodes.

- Data Writers – components that replicate the changes done in the Data Grid to the persistent storage to assure that no updates are lost if the system is shut down. There can be a pair of Reader and Writer per class of Processing Units (subdomain) or a global pair that processes all read and write requests.

SBA provides nearly perfect scalability (high read and write throughput as all the data is cached) and elasticity (new instances of Processing Units are created and initialized very quickly as they copy their data from already running units with no need to access the Persistent Database). Though for smaller datasets the entire database is replicated to every node of the grid (Replicated Cache mode), Space-Based Architecture also allows the processing of datasets that don’t fit into the memory of a single node by assigning each node a shard of the dataset (Distributed Cache mode).

The drawbacks of this architecture include:

- Structural and operational complexity.

- Very basic dictionary-like interface of the tuple space (no joins or other complex operations).

- High traffic for data replication among the nodes.

- Data collisions if multiple clients change the same piece of data simultaneously.

Shared Memory #

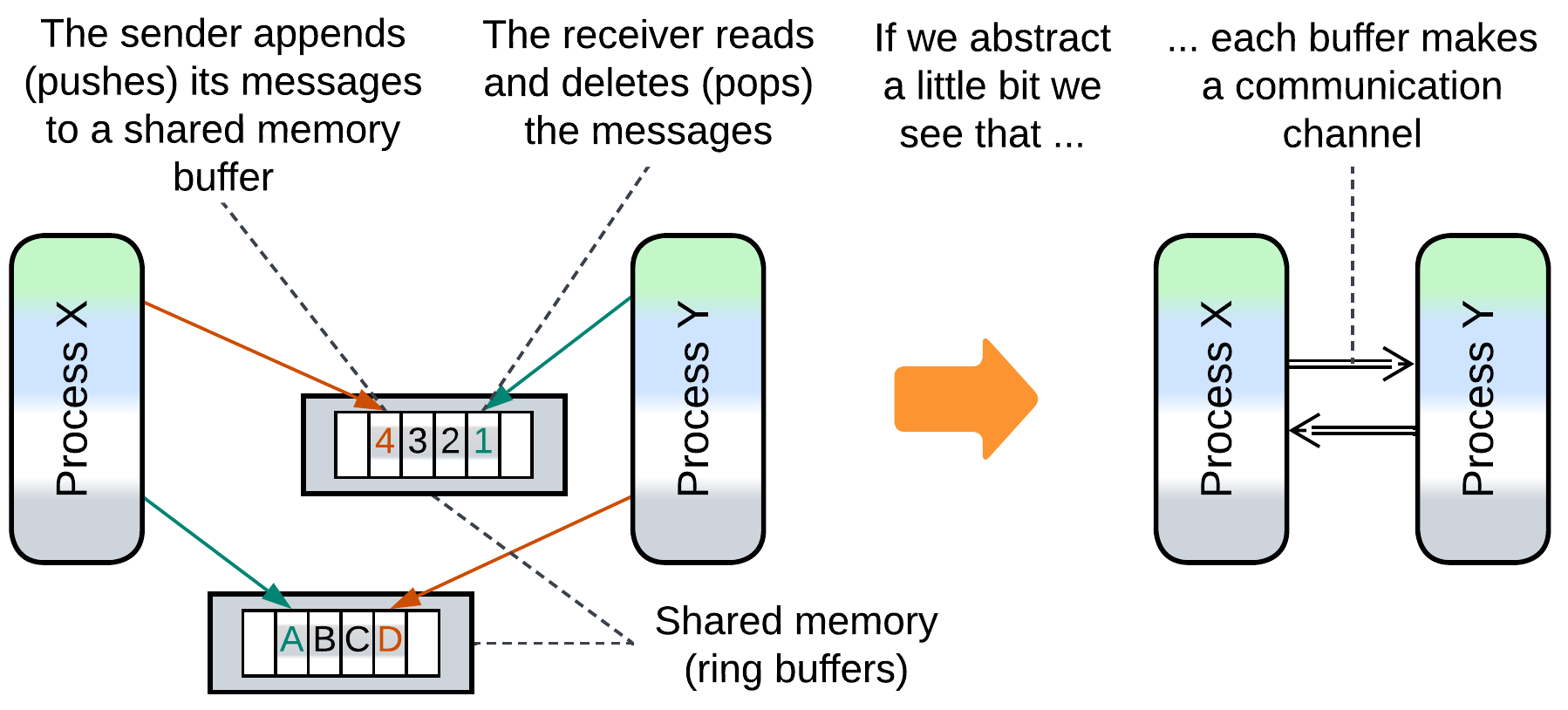

Several actors (processes, modules, device drivers) communicate through one or more mutually accessible data structures (arrays, trees, or dictionaries). Accessing a shared object may require some kind of synchronization (e.g. taking a mutex) or employ atomic variables. Notwithstanding that communication via shared memory is the archenemy of (shared-nothing) messaging it is actually used to implement messaging: high-load multi-process systems (web browsers and high-frequency trading) rely on shared memory mailboxes for messaging between their constituent processes.

Shared File System #

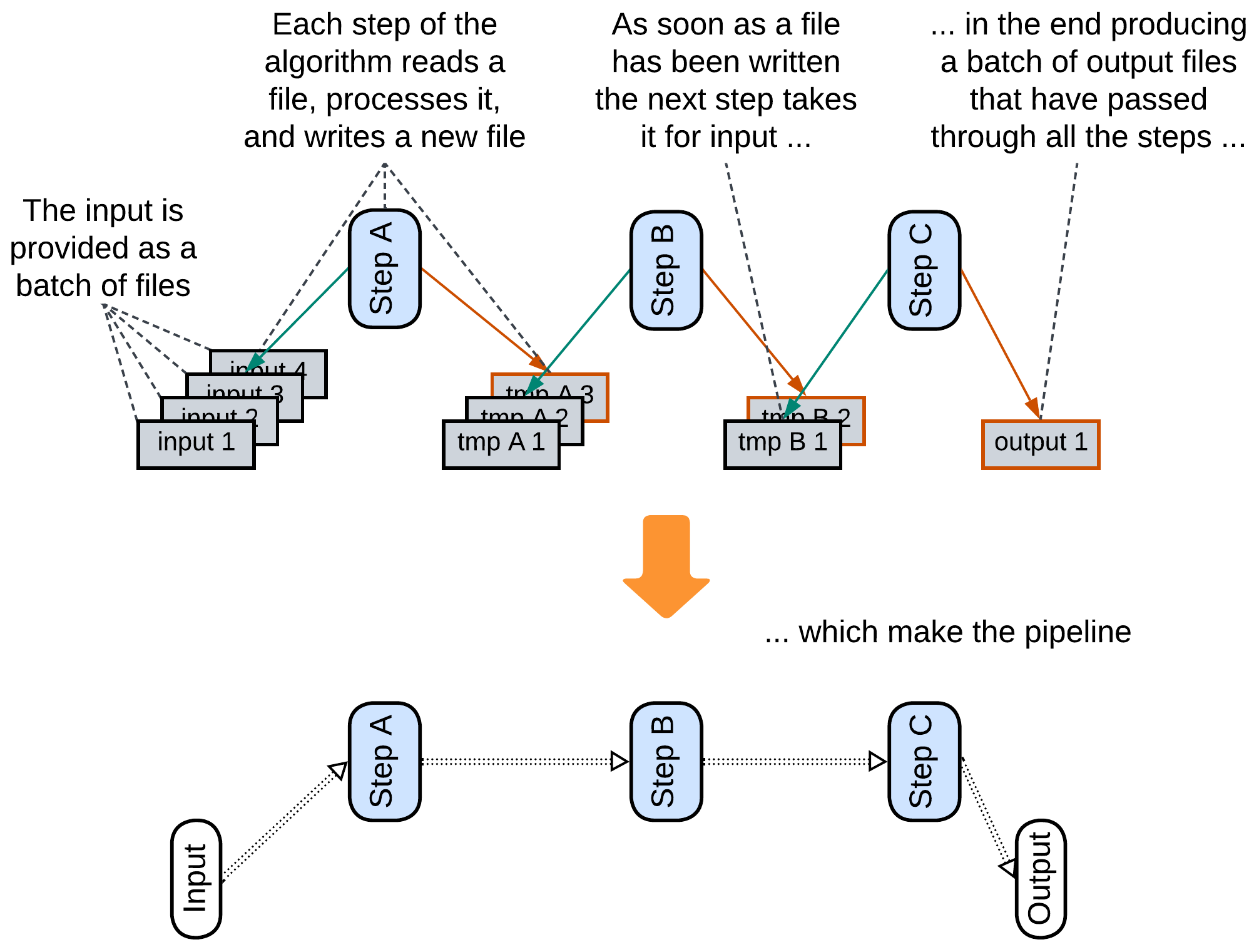

As a file system is a kind of shared dictionary, writing and reading files can be used to transfer data between applications. A data processing Pipeline which stores intermediate results in files benefits from the ability to restart its calculation from the last successful step because files are persistent [DDIA].

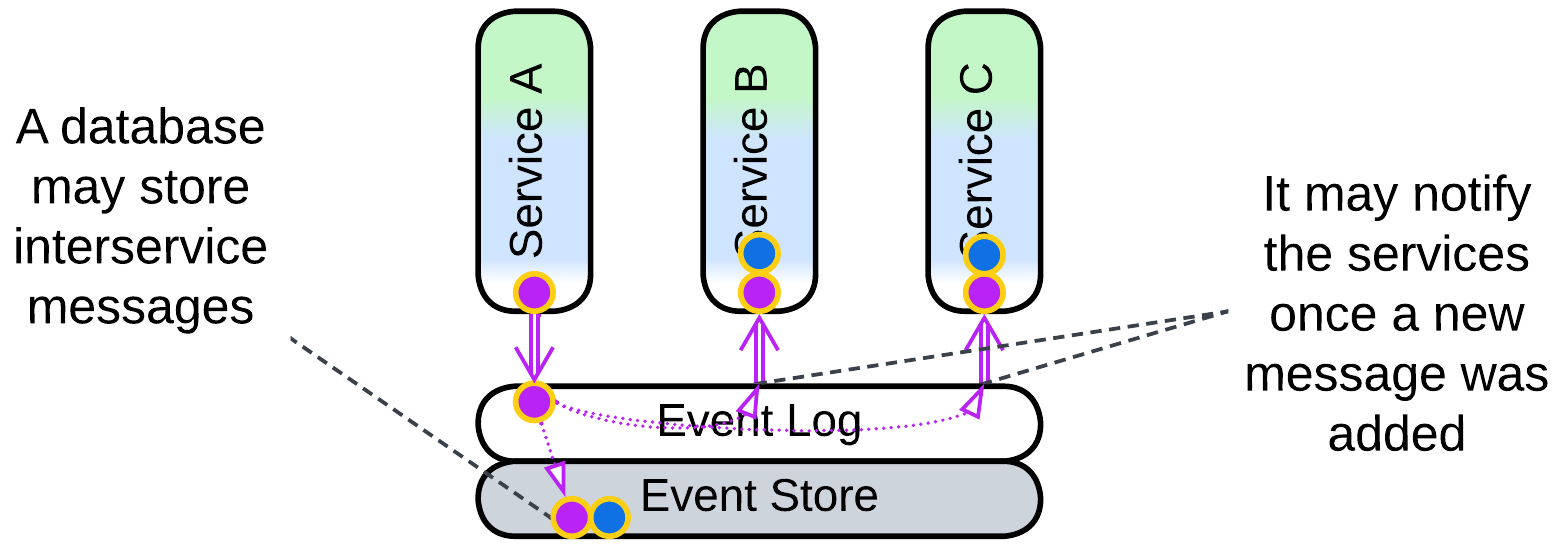

Persistent Event Log, Shared Event Store #

A database which stores events (event log for interservice events, event store for internal state changes) can be used as a Middleware: an event producer writes its events to a topic in the repository while event consumers get notified as soon as a new record appears.

More details are available in the Combined Component chapter.

(inexact) Stamp Coupling #

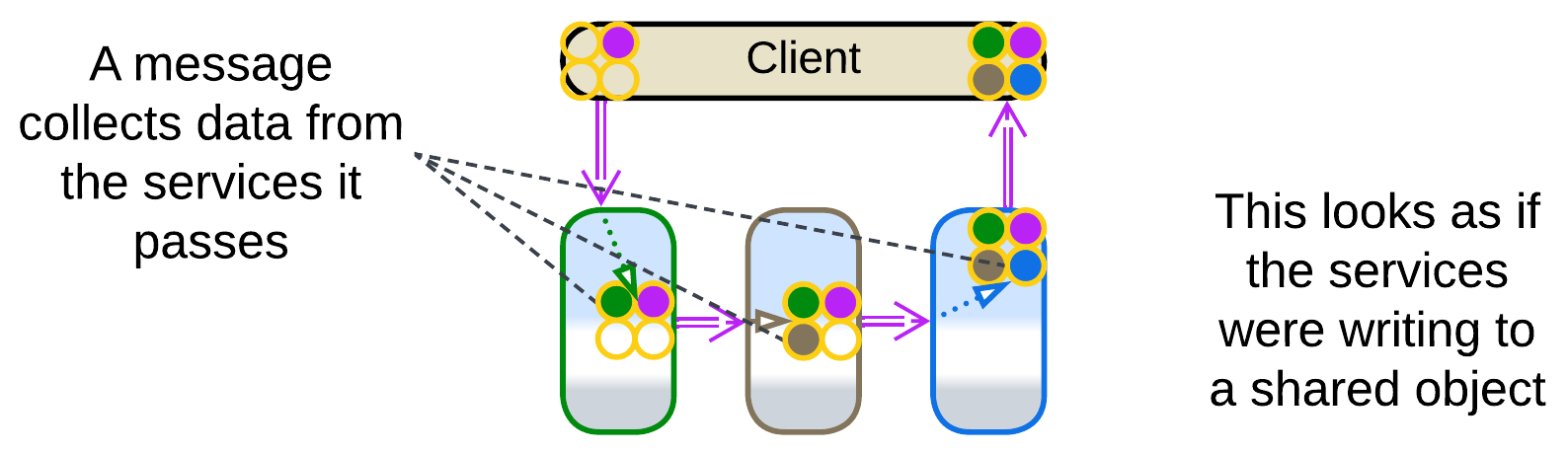

Stamp Coupling [SAHP] happens when a single data structure passes through an entire Pipeline, with separate fields of the data structure targeting individual processing steps.

A choreographed system with no shared databases does not provide any way to aggregate the data spread over its multiple services. If we need to collect everything known about a user or purchase, we pass a query message through the system, and every service appends to it whatever it knows of the subject (just like post offices add their stamps to a letter). The unified message becomes a kind of virtual (temporary) Shared Repository which the services (Content Enrichers according to [EIP]) write to. This also manifests in the dependencies: all the services depend on the format of the query message as they would on the schema of a Shared Repository, instead of depending on each other, as is usual with Pipelines.

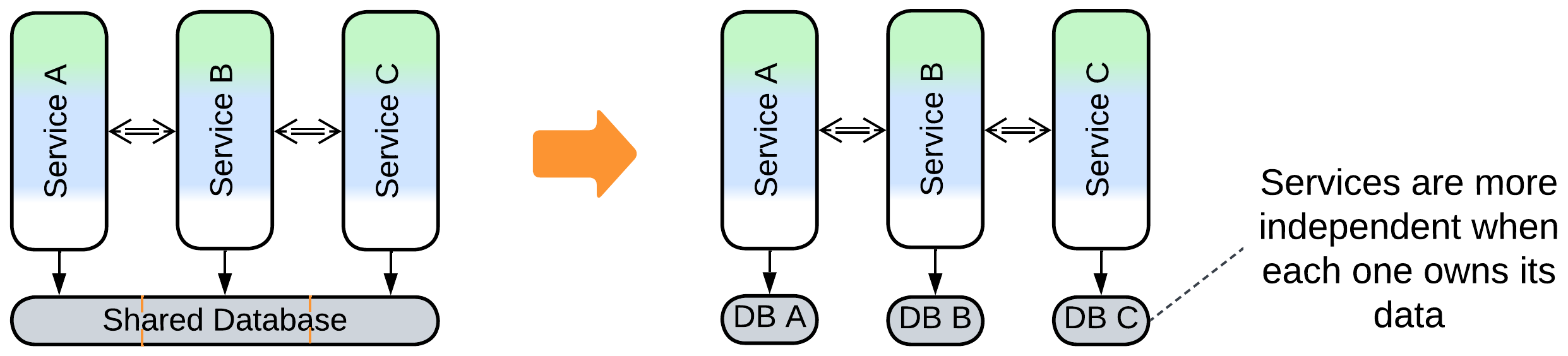

Evolutions #

Once a database appears, it is unlikely to go away. I see the following evolutions to improve performance of the data layer:

- Shard the database.

- Use Space-Based Architecture for dynamic scalability.

- Divide the data into private databases.

- Deploy specialized databases (Polyglot Persistence).

Summary #

A Shared Repository encapsulates a system’s data, allowing for data-centric development and kickstarting Service-Based architectures through simplifying interservice interactions. Its downsides are a frozen data schema and limited performance.