Orchestrator #

One ring to rule them all. Make a service to integrate other services.

Known as: Orchestrator [MP, FSA], Orchestrated Services, Service Layer [PEAA], Application Layer [DDD], Wrapper Facade [POSA4], Multi-Worker [DDS], Controller / Control, Workflow Owner [FSA] of Microservices, and Processing Grid [FSA] of Space-Based Architecture.

Aspects:

Variants:

By transparency:

- Closed or strict,

- Open or relaxed.

By structure (not exclusive):

- Monolithic,

- Sharded,

- Layered [FSA],

- A service per client type (Backends for Frontends),

- A service per subdomain [FSA] (Hierarchy),

- A service per use case [SAHP] (SOA-style).

By function:

- API Composer [MP] / Remote Facade [PEAA] / Gateway Aggregation / Composed Message Processor [EIP] / Scatter-Gather [EIP, DDS] / MapReduce [DDS],

- Process Manager [EIP, LDDD] / Orchestrator [FSA],

- (Orchestrated) Saga [LDDD] / Saga Orchestrator [MP] / Saga Execution Component / Transaction Script [PEAA, LDDD] / Coordinator [POSA3],

- Integration (Micro-)Service / Application Service,

- (with a Gateway) API Gateway [MP] / Microgateway,

- (with a Middleware) Event Mediator [FSA],

- (with a Middleware and Adapters) Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) [FSA].

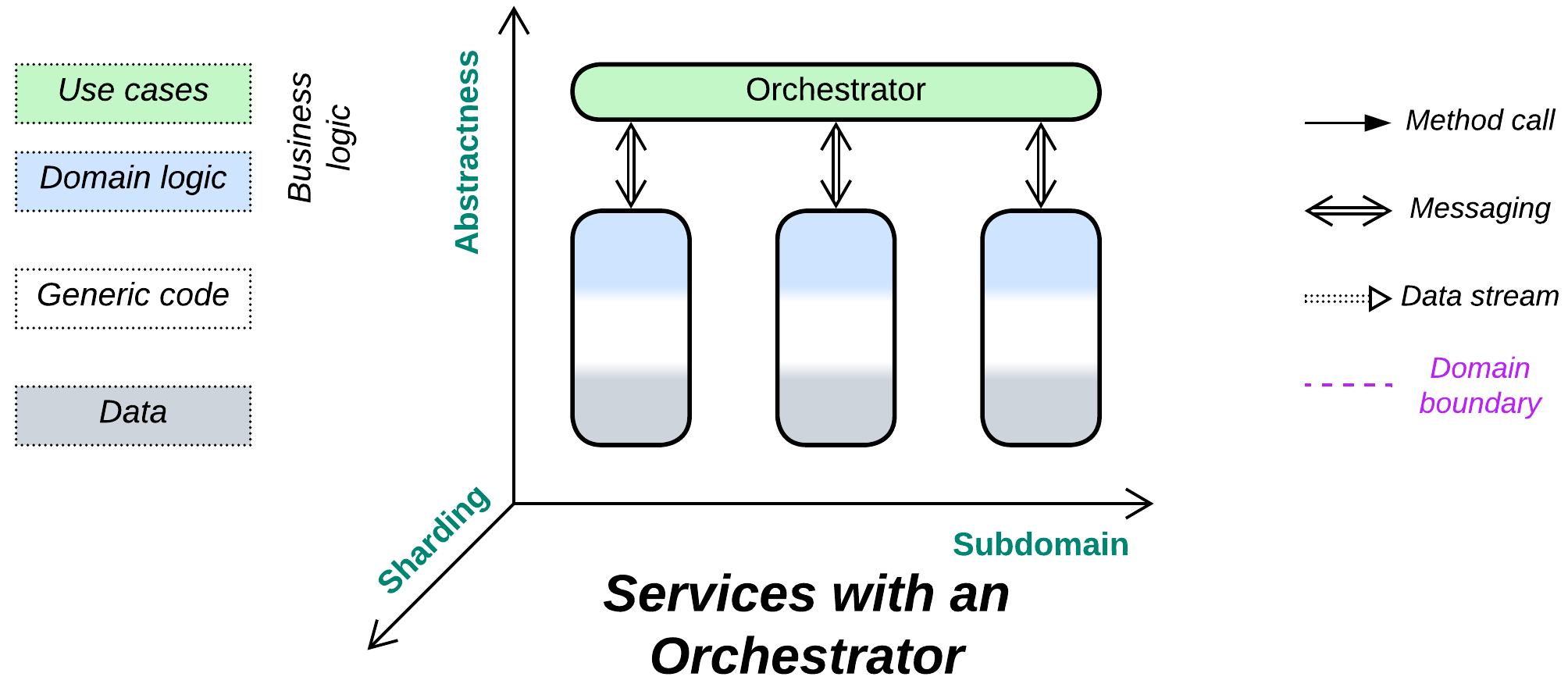

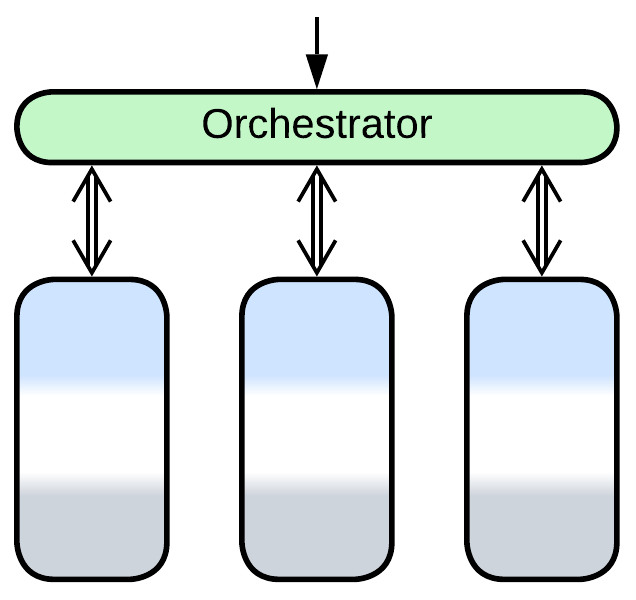

Structure: A layer of high-level business logic built on top of lower-level services.

Type: Extension.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Separates integration concerns from the services – decouples the services’ APIs | May increase latency for global use cases |

| Global use cases can be changed and deployed independently from the services | Qualities of the services become coupled to an extent |

| Decouples the services from the system’s clients | API design is an extra step before implementation |

References: [FSA] discusses orchestration in its chapters on Event-Driven Architecture, Service-Oriented Architecture, and Microservices. [MP] describes orchestration-based Sagas and its Order Service acts as an Application Service without explicitly naming the pattern. [POSA4] defines several variants of Facade.

An Orchestrator takes care of global use cases (those involving multiple services) thus allowing each service to specialize in its own subdomain and, ideally, forget about the existence of all the other services. This way the entire system’s high-level logic (which is subject to frequent changes) is kept (and deployed) together, isolated from usually more complex subdomain-specific services. Dedicating a layer to global scenarios makes them relatively easy to implement and debug, while the corresponding development team that communicates with clients shelters other narrow-focused teams from disruptions. The cost of employing an Orchestrator is both degraded performance when compared to basic Services that rely on choreography [FSA, MP] and some coupling of the properties of the orchestrated services as the Orchestrator usually treats every service in the same way.

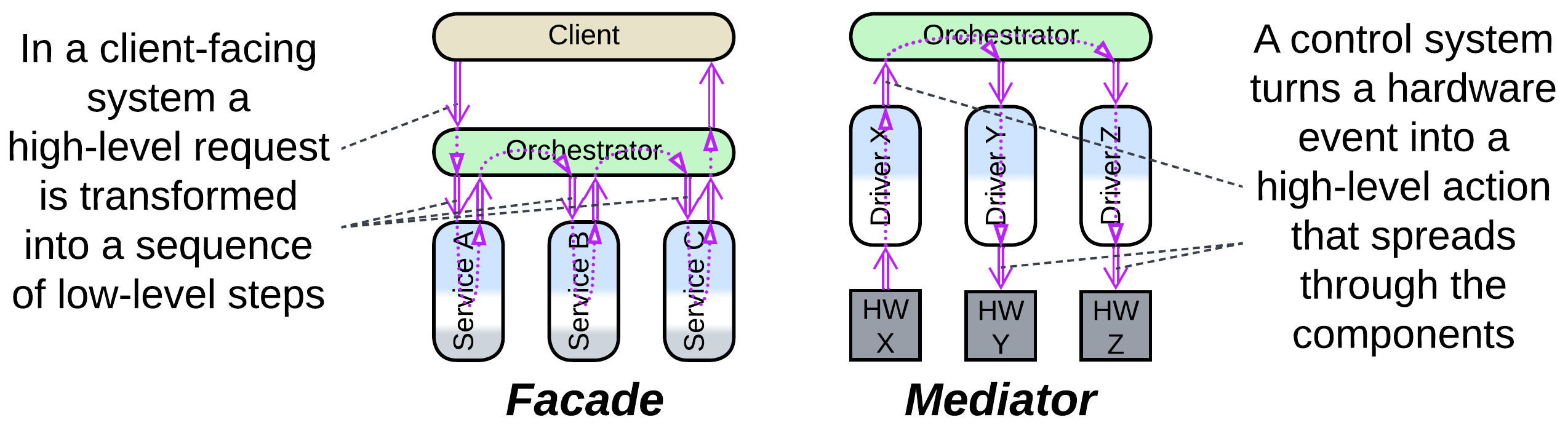

An Orchestrator fulfills two closely related roles:

- As a Mediator [GoF, SAHP] it keeps the states of the underlying components (services) consistent by propagating changes that originate in one component to the rest of the system. This role is prominent in control software, pervading automotive, aerospace, and IoT industries. The Mediator role also emerges as Saga [MP].

- As a Facade [GoF] it builds high-level scenarios out of smaller steps provided by the services or modules it controls. This role is obvious for processing systems where clients communicate with the Facade, but it is also featured in control software, because sometimes a simple event may trigger a complex multi-component scenario managed by the system’s Orchestrator.

Data processing systems, such as backends, may deploy multiple instances of stateless Orchestrators to improve stability and performance. In contrast, an Orchestrator in control software incorporates the highest-level view of the system’s state thus it cannot be easily replicated (as any replicated state must be kept synchronized, introducing delay or inconsistency in decision-making).

Performance #

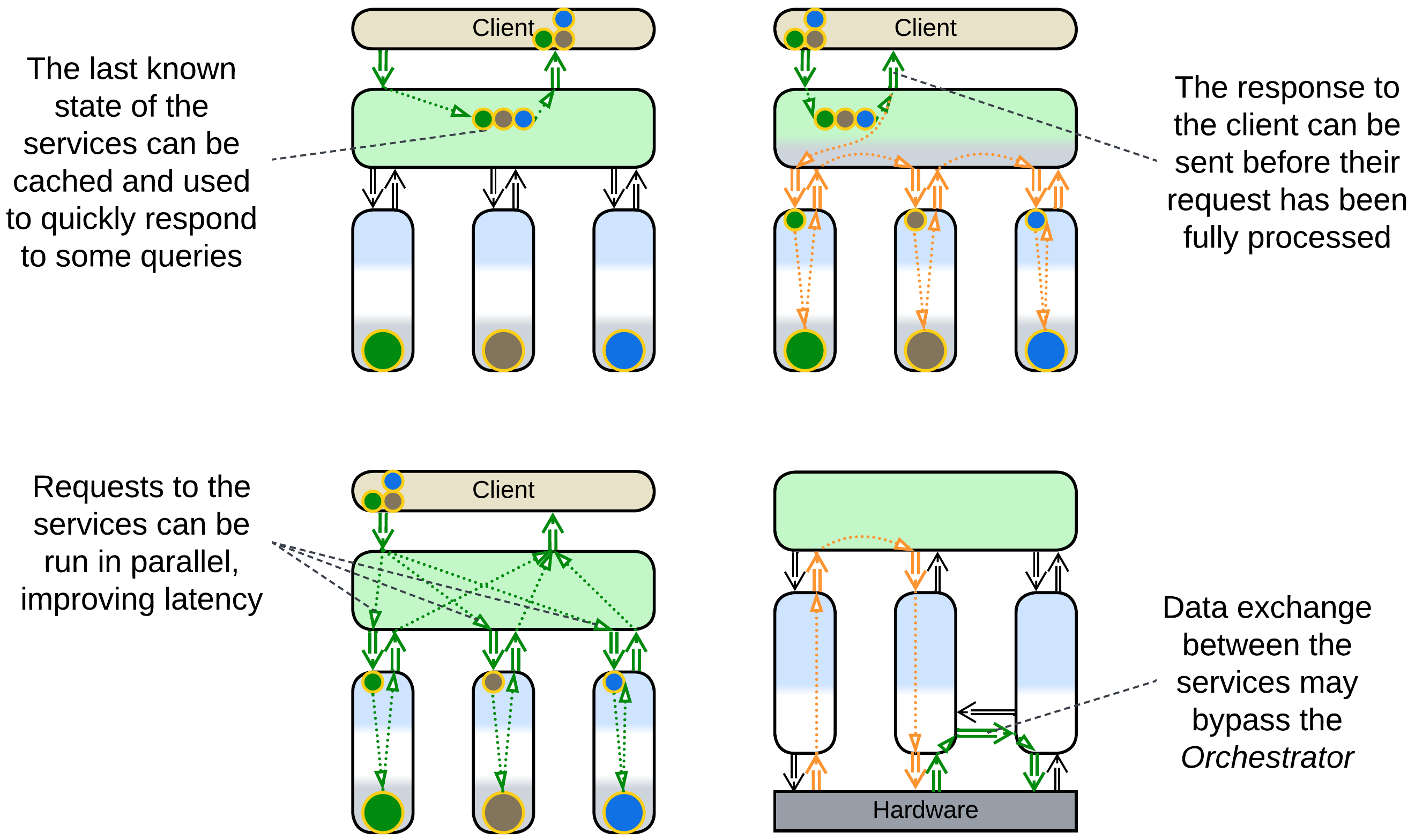

When compared to choreography, orchestration usually worsens latency as it involves extra steps of communication between the Orchestrator and orchestrated components. However, the effects should be estimated on case by case basis, as there are exceptions in at least the following cases:

- An Orchestrator may cache the state of the orchestrated system, gaining the ability to immediately respond to read requests with no need to query the underlying components. This is very common with control systems.

- An Orchestrator may persist a write request, respond to the client, and then start the actual processing. Persistence grants that the request will eventually be completed as it can be restarted.

- An Orchestrator may run multiple subrequests in parallel, reducing latency compared to a chain of choreographed events.

- In a highly loaded or latency-critical system, orchestrated services may establish direct data streams that bypass the Orchestrator. A classic example is VoIP where the call establishment logic (SIP) goes through an orchestrating server while the voice or video (RTP) is streaming directly between the clients.

I don’t see how orchestration can affect throughput as in most cases the Orchestrator can be scaled. However, scaling weakens consistency as then no instance of the Orchestrator has exclusive control over the system’s state.

Dependencies #

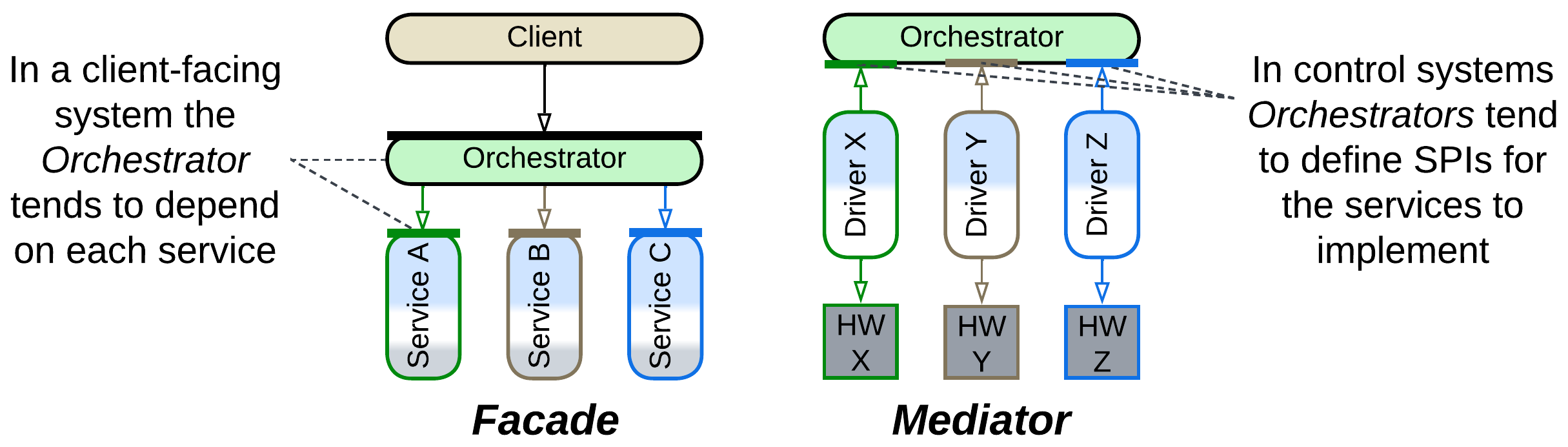

An Orchestrator may depend on the APIs of the services it orchestrates or define SPIs for them to implement, with the first mode being natural for its Facade [GoF] aspect and the second one for the Mediator [GoF]:

If an Orchestrator is added to integrate existing components, it will use their APIs.

In large projects, where each service gets a separate team, the APIs need to be negotiated beforehand, and will likely be owned by the orchestrated services.

Smaller (single-team) systems tend to be developed top-down, with the Orchestrator being the first component to implement, thus it defines the interfaces it uses.

Likewise, control systems tend to reverse the dependencies, with their services depending on the orchestrator’s SPI – either because their events originate with the services (so the services must have an easy way to contact the Orchestrator) or to provide for polymorphism between the low-level components. See the chapter on orchestration for more details.

Applicability #

Orchestrators shine with:

- Large projects. The partition of business logic into a high-level application (Orchestrator) and the multiple subdomain Services it relies on provides perfect code decoupling and team specialization.

- Specialized teams. As an improvement over Services, the teams which develop deep knowledge of subdomains will delegate communication with customers to the application team.

- Complex and unstable requirements. The integration layer (Orchestrator) should be high-level and simple enough to be easily extended or modified to cover most of the customer requests or marketing experiments without much help from the domain teams.

Orchestrators fail in:

- Huge projects. At least one aspect of complexity is going to hurt. Either the number of the subdomain services and the size of their APIs will make it impossible for an Orchestrator programmer to find the correct methods to call, or the Orchestrator itself will become unmanageable due to the number and length of its use cases. This can be addressed by dividing the Orchestrator into a layer of services (resulting in Backends for Frontends or Cell-Based Architecture) or multiple layers (often yielding Top-Down Hierarchy). It is also possible to go for the Service-Oriented Architecture as that has more fine-grained components.

- Small projects. The implementation overhead of defining and stabilizing service APIs and the performance penalty of the extra network hop may outweigh the extra flexibility of having the Orchestrator as a separate system component.

- Low latency. Any system-wide use case will make multiple calls between the application (Orchestrator) and services, with each interaction adding to the latency.

Relations #

Orchestrator:

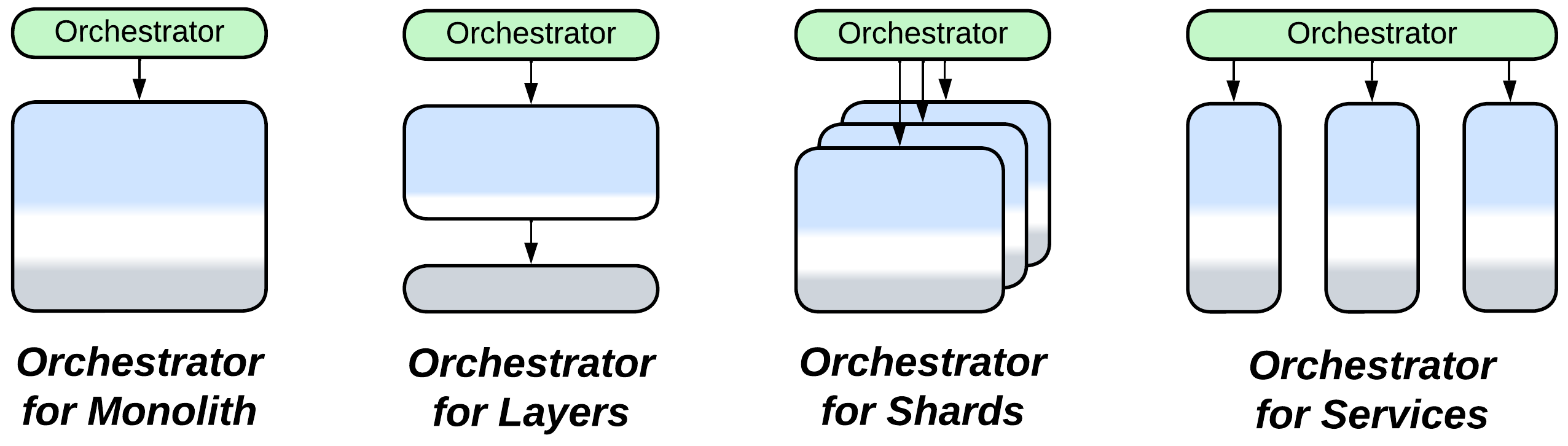

- Extends Services or, rarely, Monolith, Shards, or Layers (forming Layers).

- Can be merged with a Proxy into an API Gateway, with a Middleware into an Event Mediator, or with a Middleware and Adapters into an Enterprise Service Bus.

- Is a special case (single service) of Backends for Frontends, Service-Oriented Architecture or (2-layer) Hierarchy.

- Can be implemented by a Microkernel.

Variants by transparency #

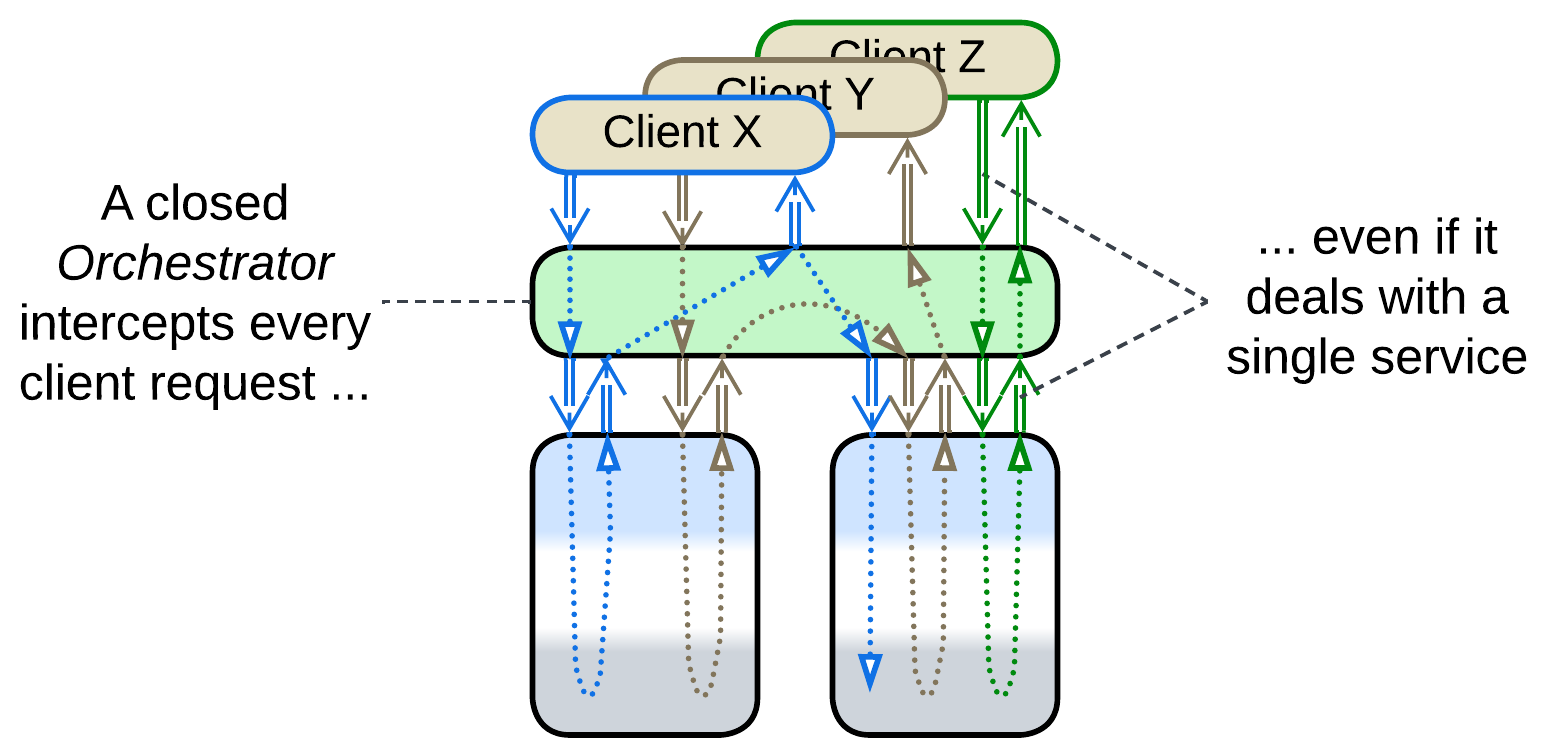

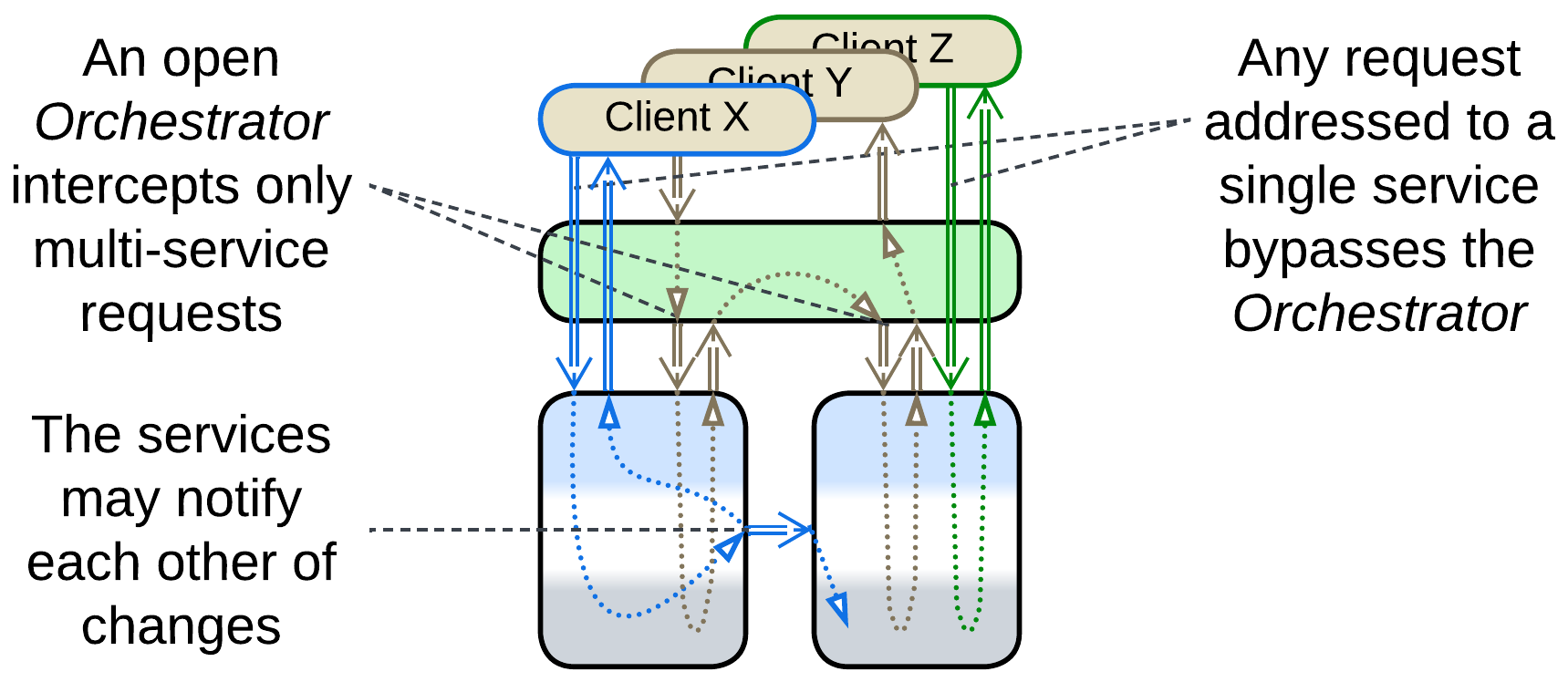

It seems that an Orchestrator, just like a layer, which it is, can be open (relaxed) or closed (strict):

Closed or strict #

A strict or closed Orchestrator isolates the orchestrated services from their users – all the requests go through the Orchestrator, and the services don’t need to intercommunicate.

Open or relaxed #

An open Orchestrator implements a subset of system-wide scenarios that require strict data consistency while less demanding requests go from the clients directly to the underlying services, which rely on choreography or shared data for communication. Such a system sacrifices the clarity of design to avoid some of the drawbacks of both choreography and orchestration:

- The orchestrator development team, which may be overloaded or slow to respond, is not involved in implementing the majority of use cases.

- Most of the use cases avoid the performance penalty caused by the orchestration.

- Failure of the Orchestrator does not disable the entire system.

- The relaxed Orchestrator still allows for synchronized changes of data in multiple services, which is rather hard to achieve with choreography.

Variants by structure (can be combined) #

The orchestration (application [DDD] / integration / composite) layer has several structural (implementation) options:

Monolithic #

A single Orchestrator is deployed. This option fits ordinary medium-sized projects.

Scaled #

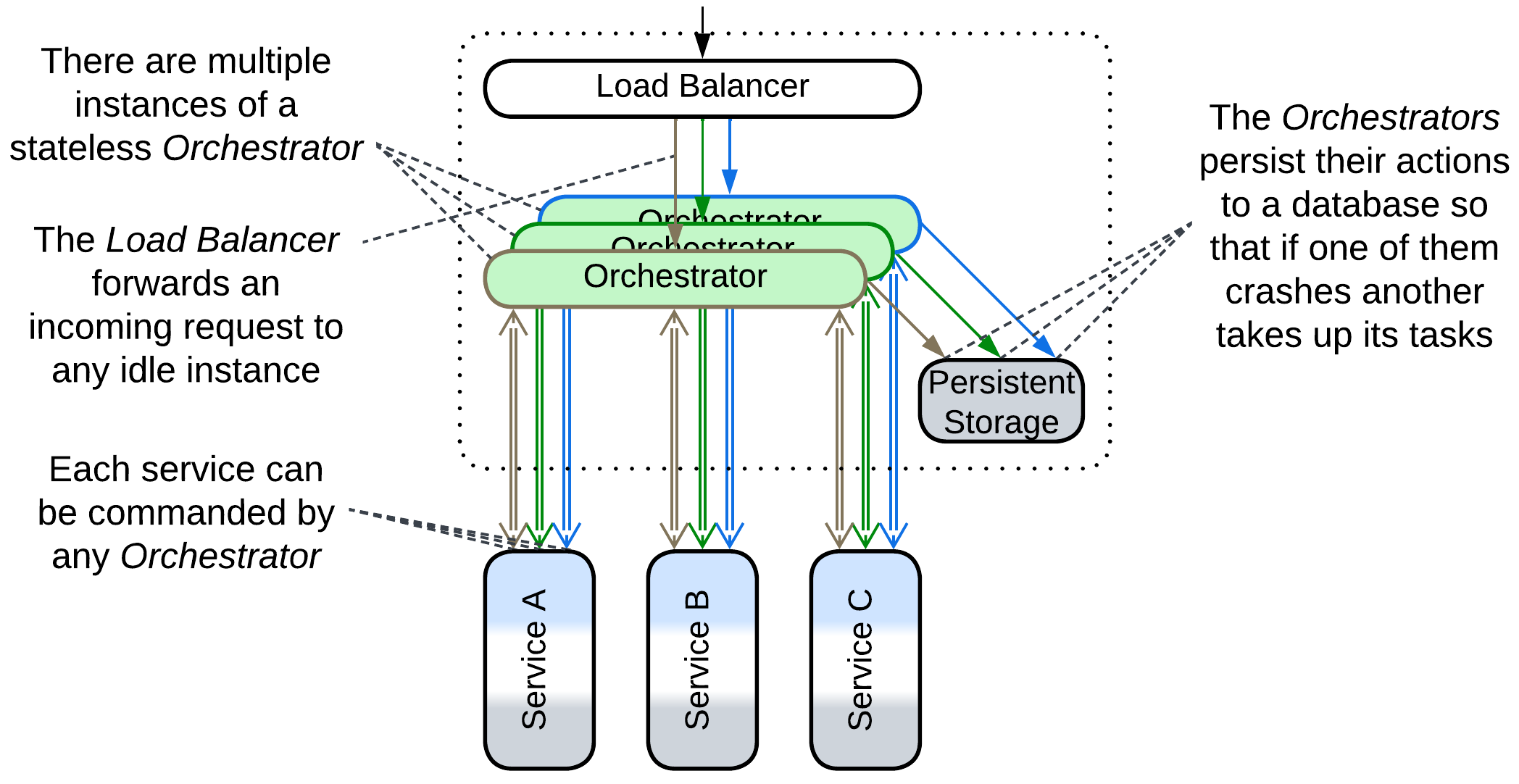

High availability requires multiple instances of a stateless Orchestrator to be deployed. A Mediator (Saga, writing Orchestrator) may store the current transaction’s state in a Shared Database to assure that if it crashes there is always another instance ready to take up its job.

High load systems also require multiple instances of Orchestrators because a single instance is not enough to handle the incoming traffic.

Not all data is made equal. For example, an online store has different requirements for reliability of its buyers’ cart contents and the payments. If the current buyers’ carts become empty when the store’s server crashes, that makes only a minor annoyance. However, any financial data loss or a corrupted money transfer is a real trouble. Therefore an online store may implement its cart with a simple in-memory Orchestrator, but should be very careful about the payments workflow, every step of which must be persisted to a reliable database.

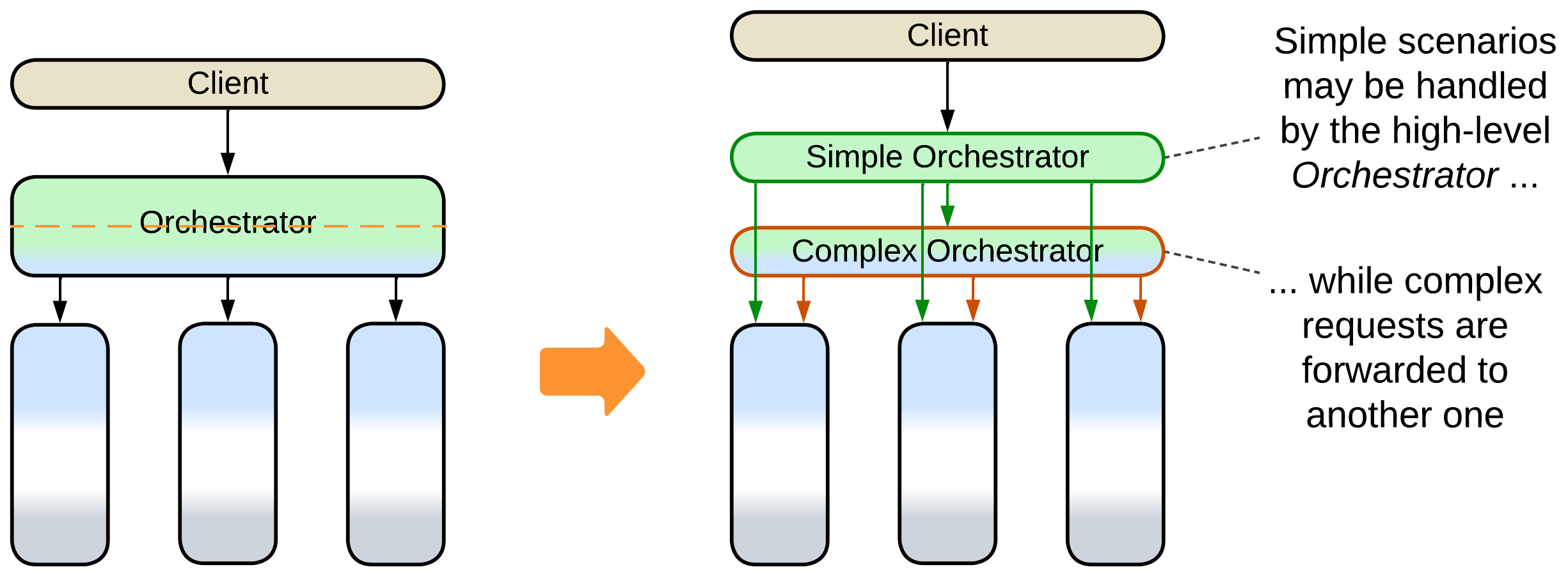

Layered #

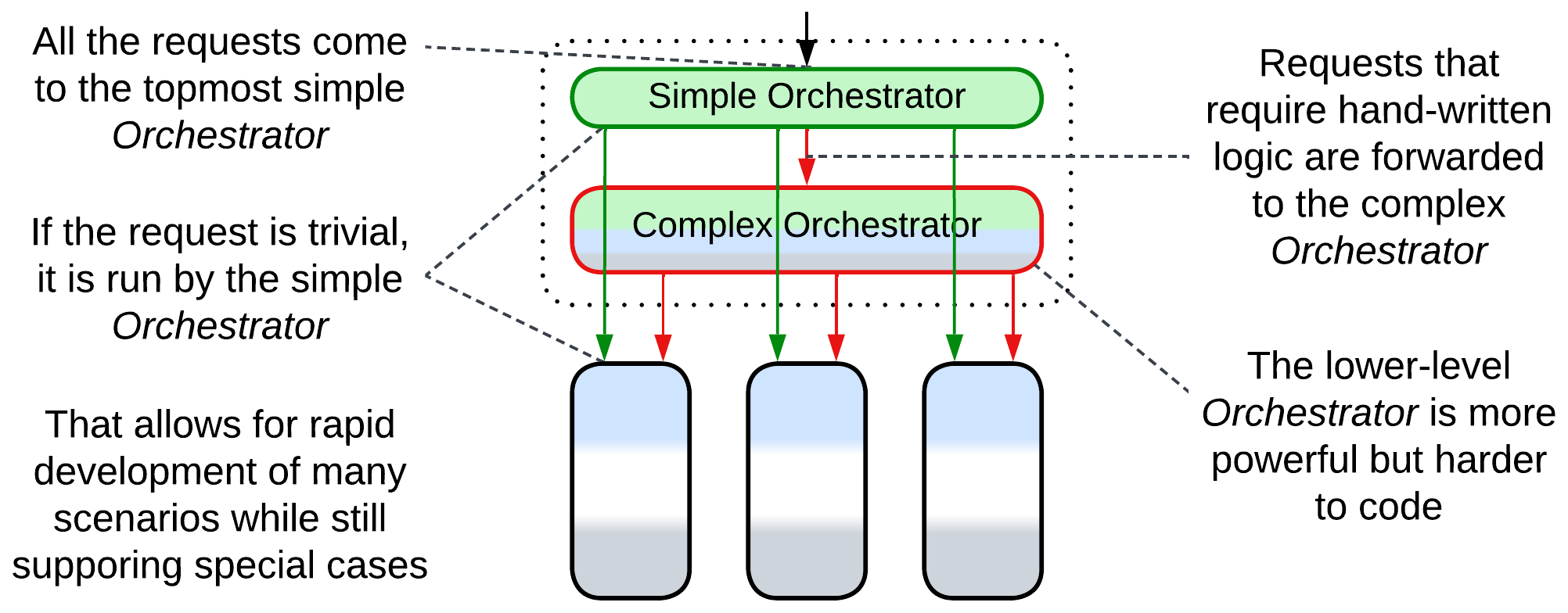

[FSA] describes an option of a layered Event Mediator. A client’s request comes to the topmost layer of the Orchestrator which uses the simplest (and least flexible) framework. If the request is found to be complex, it is forwarded to the second layer which is based on a more powerful technology. And if it fails or requires a human decision then it is forwarded again to the even more complex custom-tailored orchestration layer.

That allows the developers to gain the benefits of a high-level declarative language in a vast majority of scenarios while falling back to hand-written code for a few complicated cases. The choice is not free as programmers need to learn multiple technologies, interlayer debugging is anything but easy and performance is likely to be worse than that of a monolithic Orchestrator.

A similar example is using an API Composer for the top layer, followed by a Process Manager and a Saga Engine.

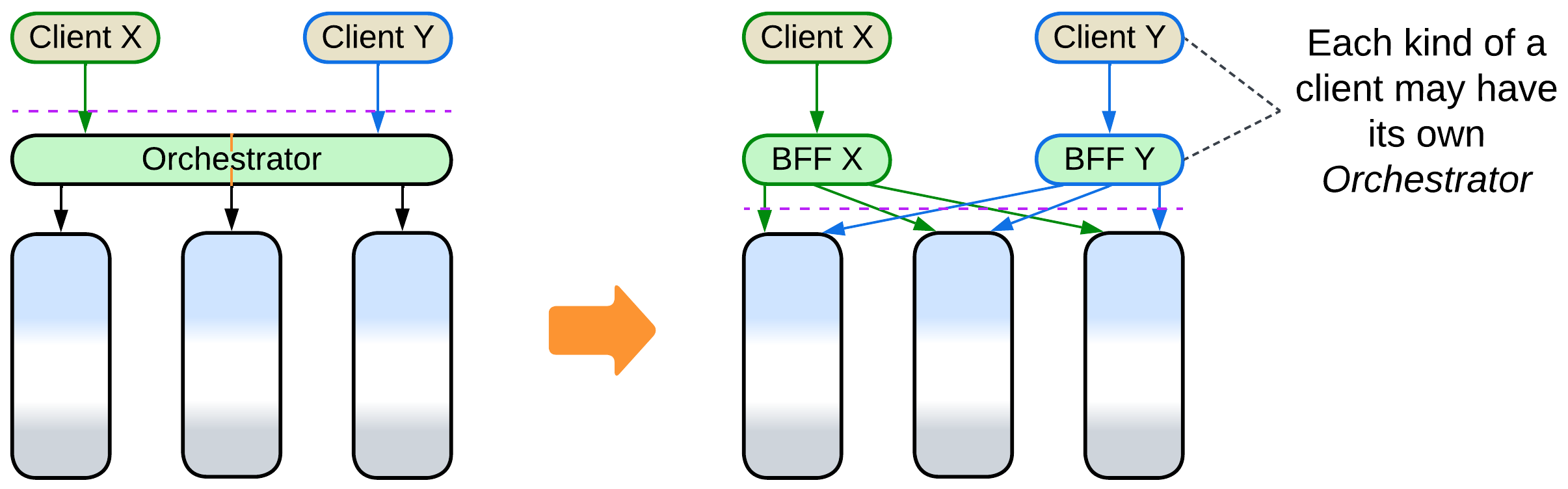

A service per client type (Backends for Frontends) #

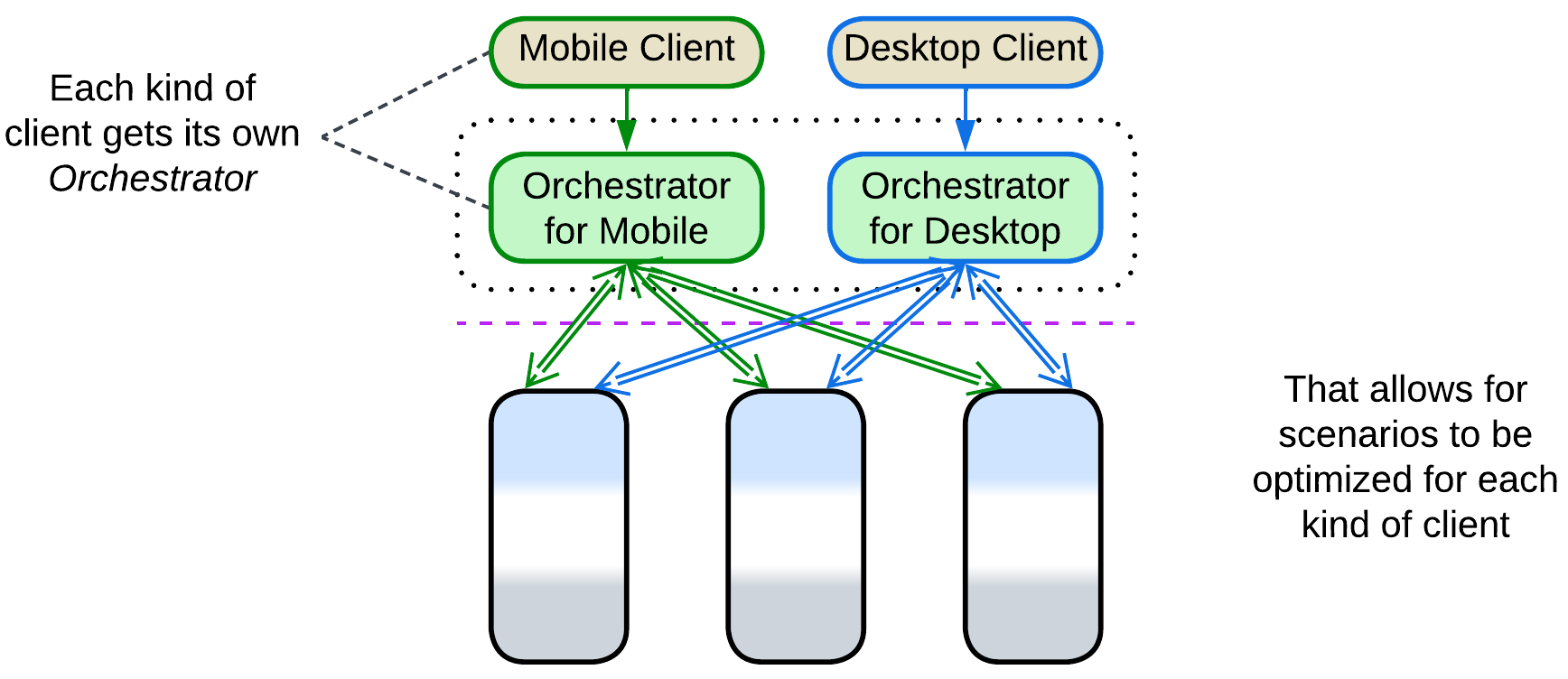

If your clients strongly differ in workflows (e.g. OLAP and OLTP, or user and admin interfaces), implementing dedicated Orchestrators is an option to consider. That makes each client-specific Orchestrator smaller and more cohesive than the unified implementation would be and gives more independence to the teams responsible for different kinds of clients.

This pattern is known as Backends for Frontends and has a chapter of its own.

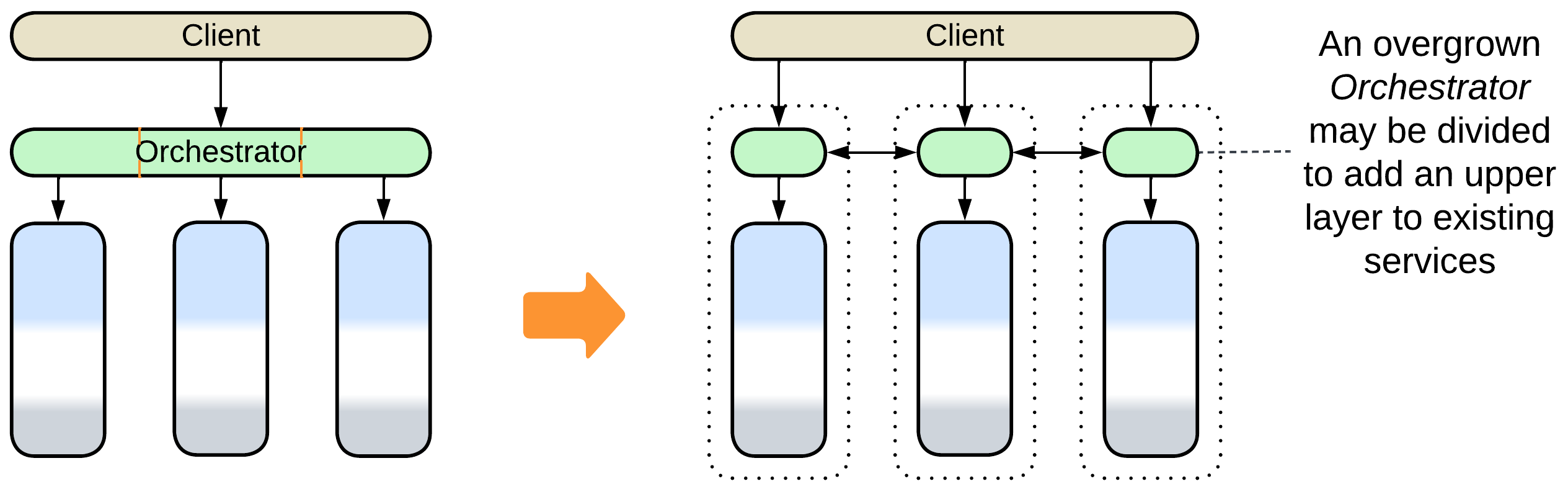

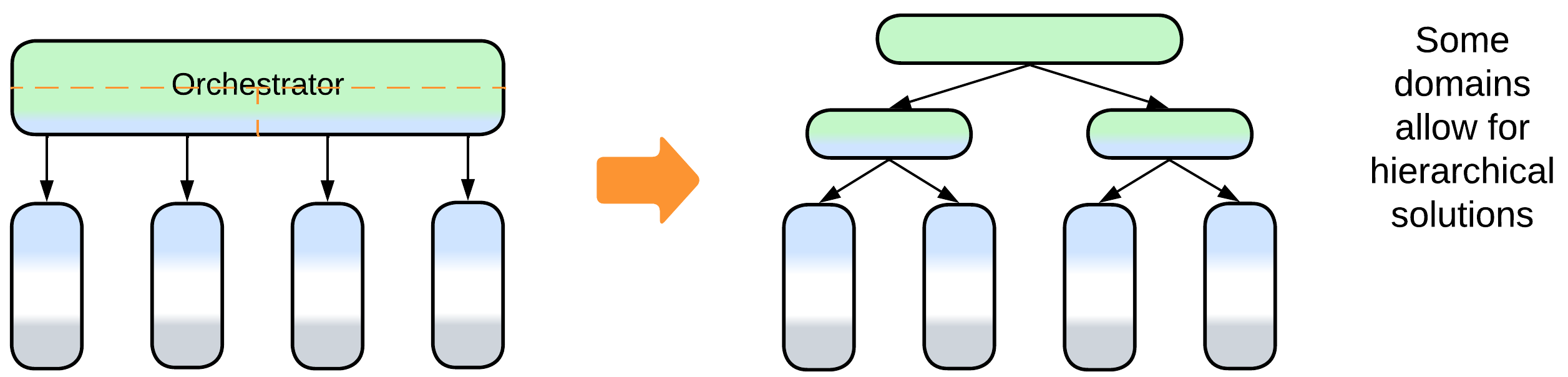

A service per subdomain (Hierarchy) #

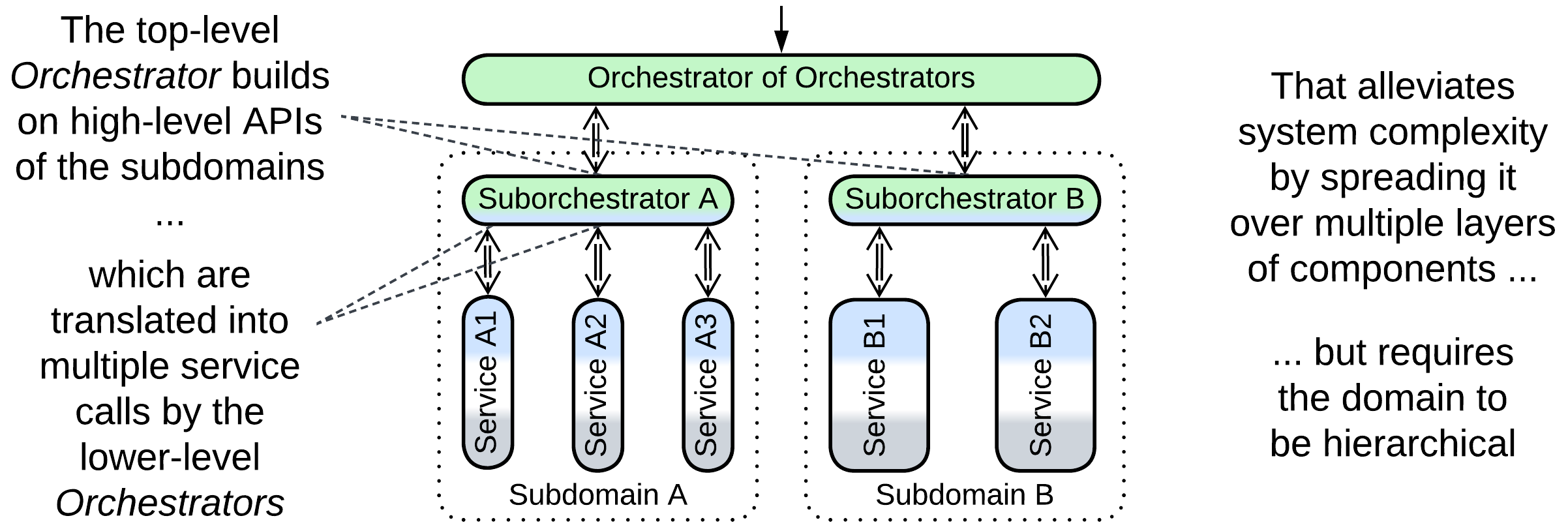

In large systems a single Orchestrator is very likely to become overgrown and turn into a development bottleneck (see Enterprise Service Bus). Building a hierarchy of Orchestrators may help [FSA], but only if the domain itself is hierarchical. The top-level component may even be a Reverse Proxy if no use cases cross subdomain borders or if the sub-orchestrators employ choreography, resulting in a flat Cell-Based Architecture. Otherwise it is a tree-like Orchestrator of Orchestrators.

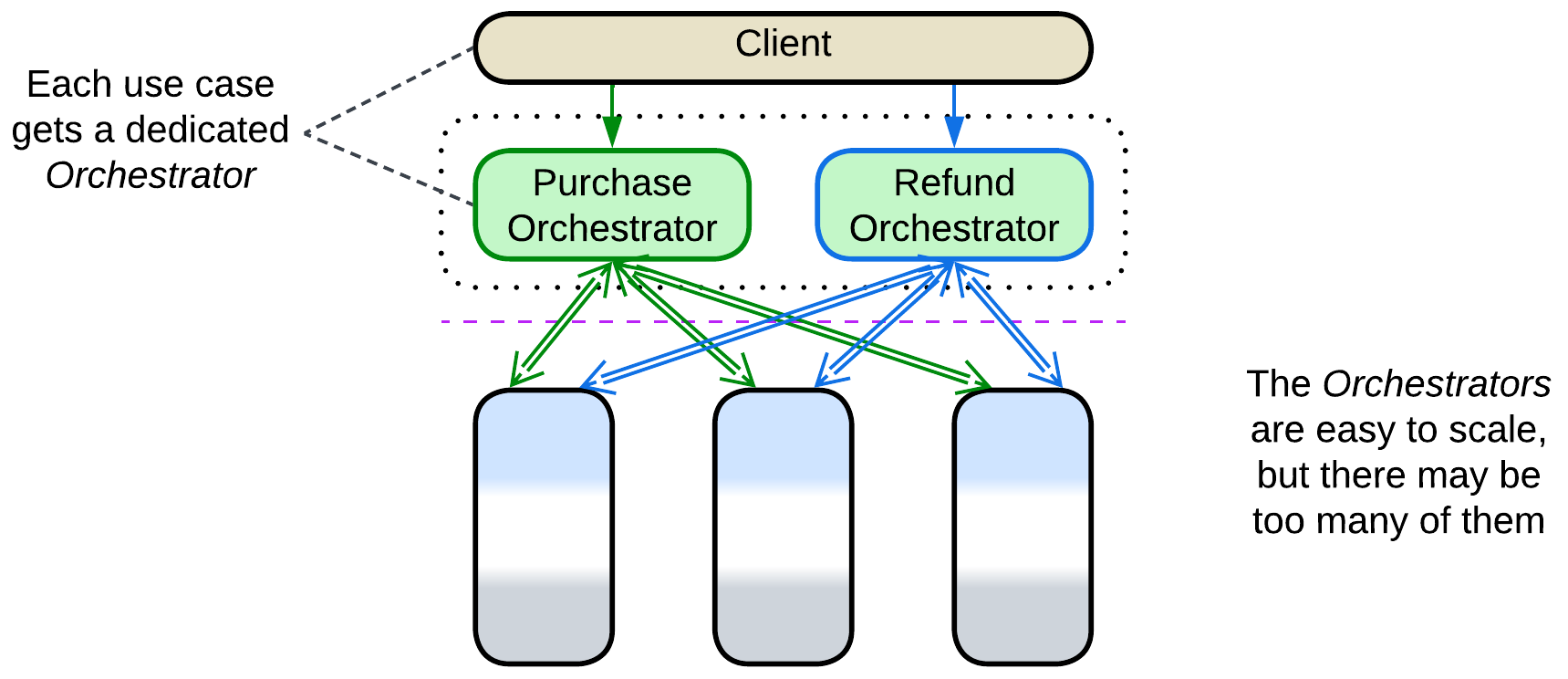

A service per use case (SOA-style) #

[SAHP] advises for single-purpose Orchestrators in Microservices: each Orchestrator manages one use case. This enables fine-grained scalability but will quickly lead to integration hell as new scenarios keep getting added to the system. Overall, such a use of Orchestrators resembles the task layer of SOA.

Variants by function #

Orchestrators may function in slightly different ways:

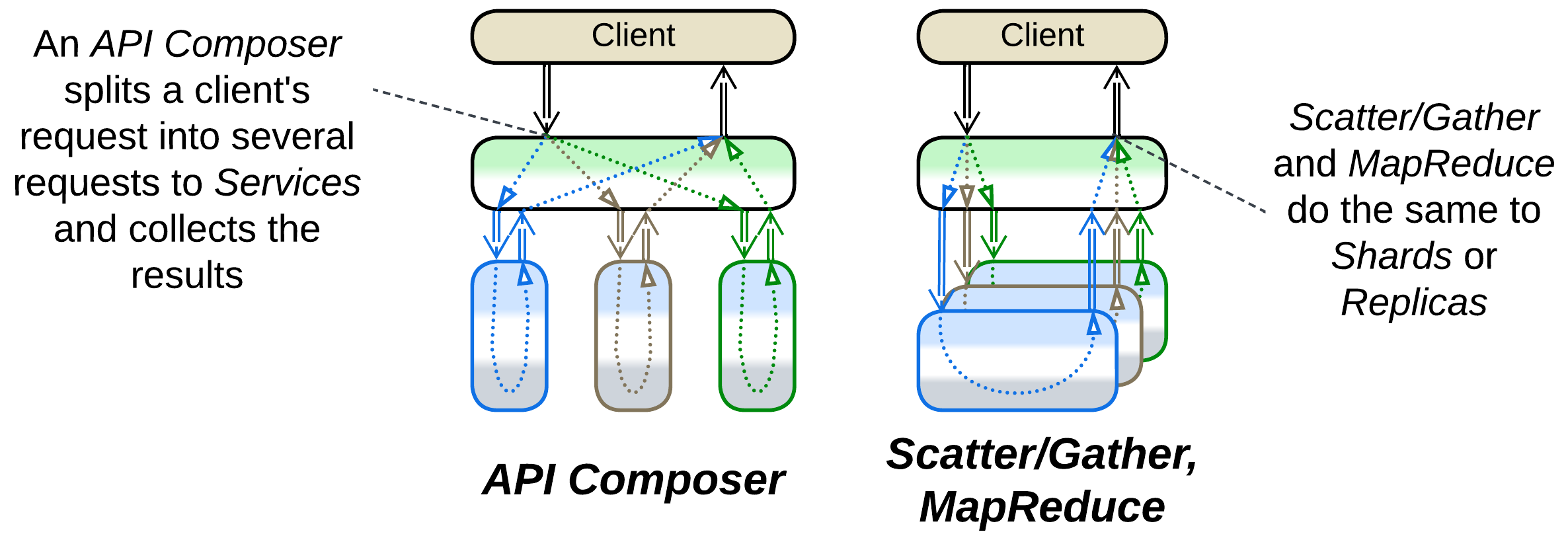

API Composer, Remote Facade, Gateway Aggregation, Composed Message Processor, Scatter-Gather, MapReduce #

API Composer [MP] is a kind of Facade [GoF] which decreases the system’s latency by translating a high-level incoming message into a set of lower-level internal messages, sending them to the corresponding services in parallel, waiting for results and collecting the latter into a response to the original message. Such a logic may often be defined declaratively in a third-party tool without writing any low-level code. Remote Facade [PEAA] is a similar pattern which makes synchronous calls to the underlying components – it exists to implement a coarse-grained protocol with the system’s clients, so that a client may achieve whatever it needs through a single request. Gateway Aggregation is a generalization of these patterns.

Composed Message Processor [EIP] disassembles API Composer into smaller components: it uses a Splitter [EIP] to subdivide the request into smaller parts, a Router [EIP] to send each part to its recipient, and an Aggregator [EIP] to collect the responses into a single message. Unlike API Composer, it can also address Shards or Replicas. A Scatter-Gather [EIP, DDS] broadcasts a copy of the incoming message to each recipient, thus it lacks a Splitter (though [DDS] seems to ignore this difference). MapReduce [DDS] is similar to Scatter-Gather except that it summarizes the results received in order to yield a single value instead of concatenating them.

If an API Composer needs to conduct sequential actions (e.g. first get user id by user name, then get user data by user id), it becomes a Process Manager which may require some coding.

An API Composer is usually deployed as a part of an API Gateway.

Example: Microsoft has an article on aggregation.

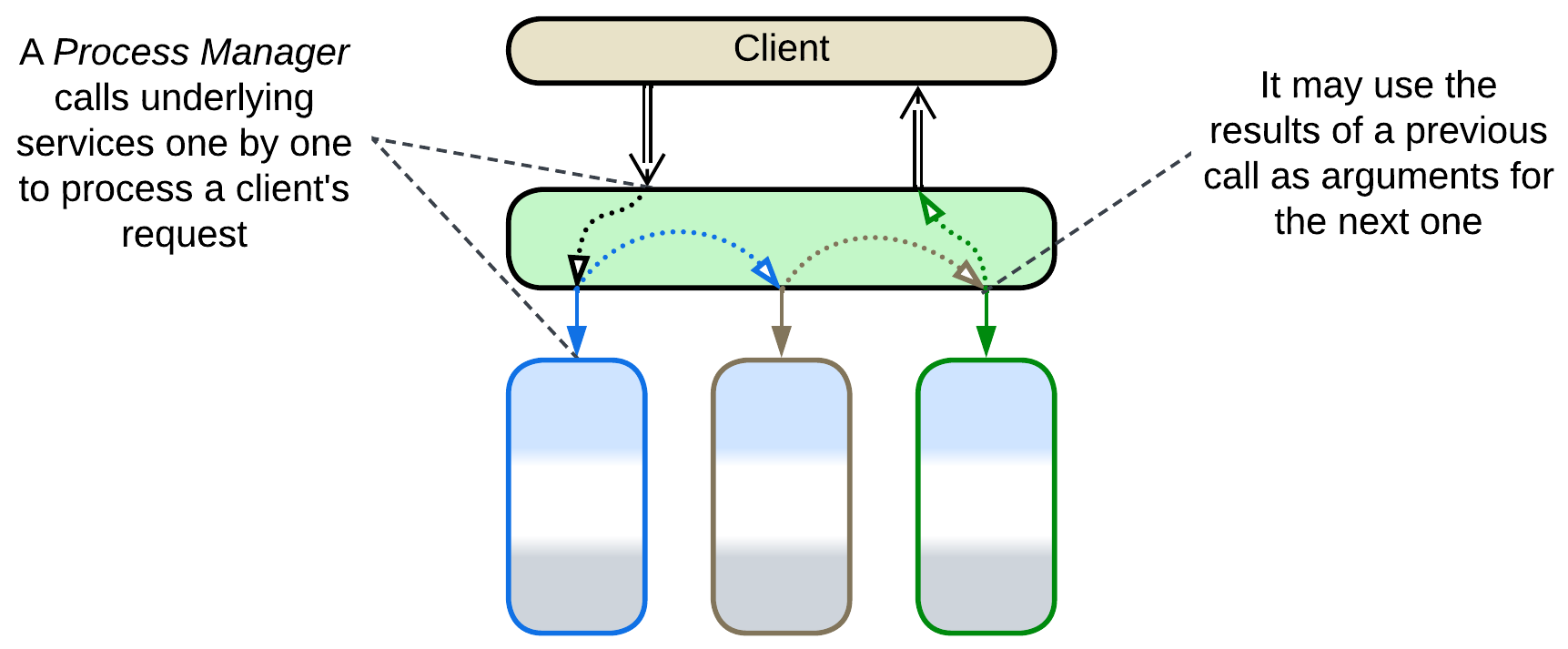

Process Manager, Orchestrator #

Process Manager [EIP, LDDD] (referred simply as Orchestrator in [FSA]) is a kind of Facade that translates high-level tasks into sequences of lower-level steps. This subtype of Orchestrator receives a client request, stores its state, runs pre-programmed request processing steps, and returns a response. Each of the steps of a Process Manager is similar to a whole task of an API Composer in that it generates a set of parallel requests to internal services, waits for the results and stores them for the future use in the following steps or final response. The scenarios it runs may branch on conditions.

A Process Manager may be implemented in a general-purpose programming language, a declarative description for a third-party tool, or a mixture thereof.

A Process Manager is usually a part of an API Gateway, Event Mediator or Enterprise Service Bus.

Example: [FSA] provides several examples.

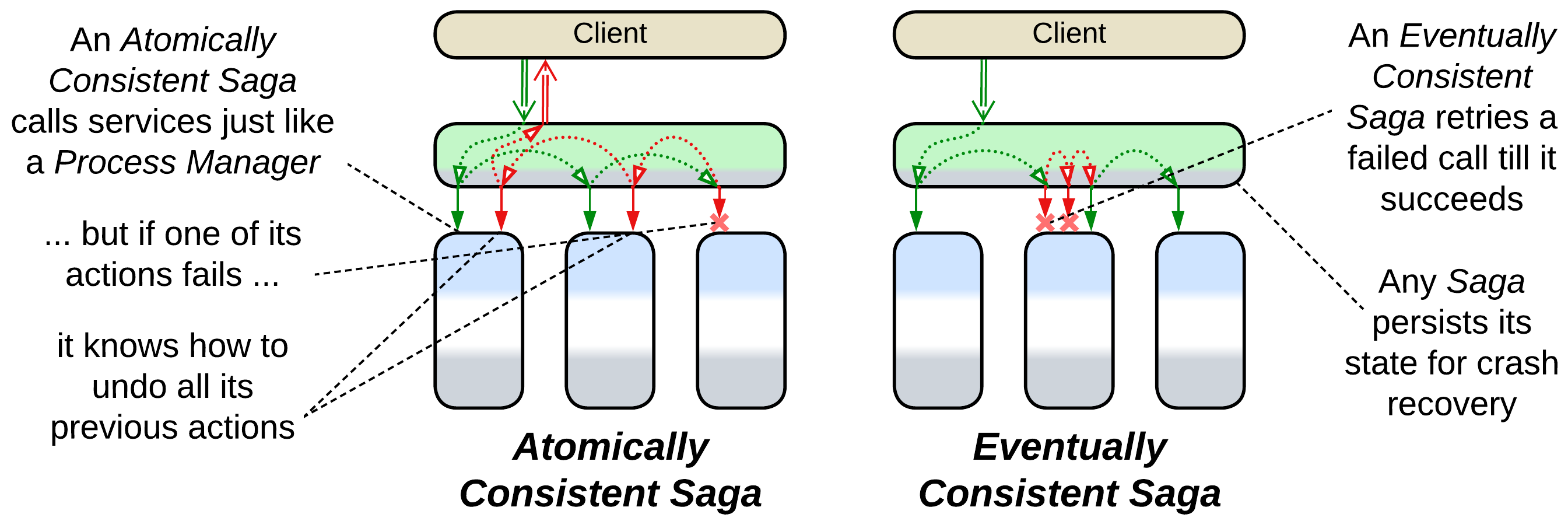

(Orchestrated) Saga, Saga Orchestrator, Saga Execution Component, Transaction Script, Coordinator #

(Orchestrated [SAHP]) Saga [LDDD], Saga Orchestrator [MP] or Saga Execution Component is a subtype of Process Manager which is specialized in distributed transactions.

An Atomically Consistent Saga [SAHP] (which is the default meaning of the term) comprises a pre-programmed sequence of {“do”, “undo”} action pairs. When it is run, it iterates through the “do” sequence till it either completes (meaning that the transaction succeeded) or fails. A failed Atomically Consistent Saga begins iterating through its “undo” sequence to roll back the changes that were already made. In contrast, an Eventually Consistent Saga [SAHP] always retries its writes till all of them succeed.

A Saga is often programmed declaratively in a third-party Saga Framework which can be integrated into any service that needs to run a distributed transaction. However, it is quite likely that such a service itself is an Integration Service as it seems to orchestrate other services.

A Saga plays the roles of both Facade by translating a single transaction request into a series of calls to the services’ APIs and Mediator by keeping the states of the services consistent (the transaction succeeds or fails as a whole). Sometimes a Saga may include requests to external services (which are not parts of the system you are developing).

A Transaction Script [PEAA, LDDD] is a procedure that executes a transaction, possibly over multiple databases [LDDD]. Unlike a Saga, it is synchronous, written in a general programming language, and does not require a dedicated framework to run. It operates database(s) directly while a Saga usually sends commands to services. A Transaction Script may return data to its caller.

Coordinator [POSA3] is a generalized pattern for a component which manages multiple tasks (e.g. software updates of multiple components) to achieve “all or nothing” results (if any update fails, other components are rolled back).

Example: [SAHP] investigates many kinds of Sagas while [MP] has a shorter description.

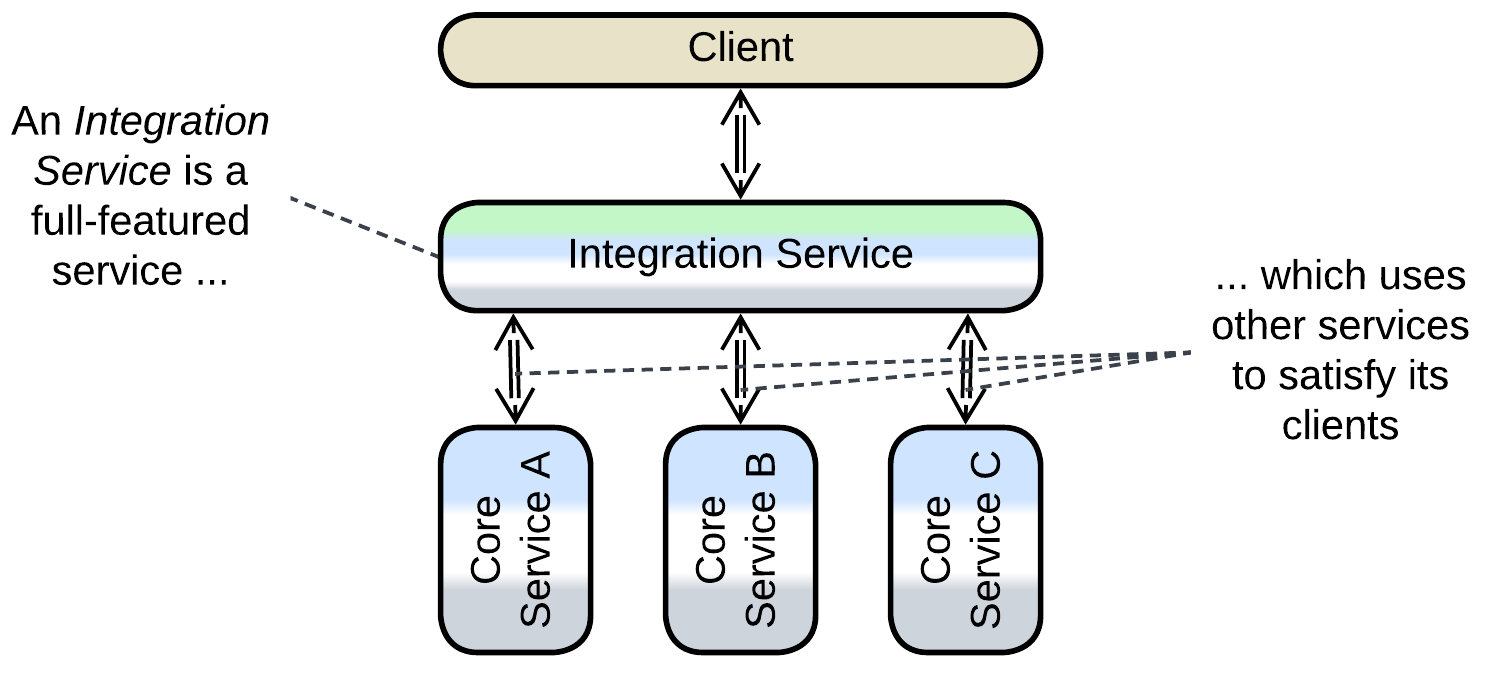

Integration (Micro-)Service, Application Service #

An Integration Service is a full-scale service (often with a dedicated database) that runs high-level scenarios while delegating the bulk of the work to several other services (remarkably, delegating to a single component forms Layers). Though an Integration Service usually features both functions of Orchestrator, in a control system its Mediator role is more prominent while in processing software it is going to behave more like the Facade. A system with an Integration Service often resembles a shallow Top-Down Hierarchy.

Example: Order Service in [MP] seems to fit the description.

Variants of composite patterns #

Several composite patterns involve an Orchestrator and are dominated by its behavior:

API Gateway #

An API Gateway [MP] is a component that processes client requests (and encapsulates an implementation of a client protocol(s)) as a Gateway (a kind of Proxy) but also splits every client request into multiple requests to internal services as an API Composer or Process Manager (which are Orchestrators). It is a common pattern for backend solutions as it provides all the means to isolate the stable core of the system’s implementation from its fickle clients. Usually a third-party framework implements and colocates both its aspects, namely Proxy and Orchestrator, thus simplifying deployment and improving latency.

Example: a thorough article from Microsoft.

Event Mediator #

Event Mediator [FSA] is an orchestrating Middleware. It not only receives requests from clients and turns each request into a multistep use case (as a Process Manager) but it also manages the deployed instances of services and acts as a medium which transports requests to the services and receives confirmations from them. Moreover, unlike an ordinary Middleware, it seems to be aware of all of the kinds of messages in the system and which service each message must be forwarded to, resulting in overwhelming complexity concentrated in a single component which does not even follow the principle of separation of concerns. [FSA] recommends building a hierarchy of Event Mediators from several vendors, further complicating the architecture.

Example: Mediator Topology in the chapter of [FSA] on Event-Driven Architecture.

Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) #

Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) [FSA] is an overgrown Event Mediator that incorporates lots of cross-cutting concerns, including protocol translation for which it utilizes at least one Adapter per service. The combination of a central role in organizations and its complexity was among the main reasons for the demise of Enterprise Service-Oriented Architecture.

Example: Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture in [FSA].

Evolutions #

Employing an Orchestrator has two pitfalls:

- The system becomes slower because too much communication is involved.

- A single Orchestrator may grow too large and rigid.

There is one way to counter the first point and more than one to solve the second:

- Subdivide the Orchestrator by the system’s subdomains, forming Layered Services and minimizing network communication.

- Subdivide the Orchestrator by the type of client, forming Backends for Frontends.

- Add another layer of orchestration.

- Build a Top-Down Hierarchy.

Summary #

An Orchestrator distills the high-level logic of your system and keeps it together in a layer which integrates other components. However, the separation of business logic into two layers results in much communication which impairs performance.