Services #

Divide and conquer. Gain flexibility through decoupling subdomains.

Known as: Services, Domain Services [FSA and SAHP, but not DDD].

Variants: Pipeline has a dedicated chapter. Many modifications are listed in the Evolutions section.

By isolation:

- Synchronous modules: Modular Monolith [FSA] (Modulith),

- Asynchronous modules: Modular Monolith (Modulith) / Embedded Actors,

- Multiple processes,

- Distributed runtime: Function as a Service (FaaS) (including Nanoservices) / Backend Actors,

- Distributed services: Service-Based Architecture [FSA] / Space-Based Architecture [FSA] / Microservices.

By communication:

- Direct method calls,

- RPCs and commands (request/confirm pairs),

- Notifications (pub/sub) and shared data,

- (inexact) No communication.

By size:

- Whole subdomain: Domain Services [FSA],

- Part of a subdomain: Microservices,

- Class-like: Actors,

- Single function: FaaS [DDS] / Nanoservices.

By internal structure:

- Monolithic service,

- Layered service,

- Hexagonal service,

- Scaled service,

- Cell (WSO2 definition) (service of services) / Domain (Uber definition) / Cluster [DEDS].

Examples:

- Service-Based Architecture [FSA but not DEDS],

- Microservices [MP, FSA],

- Actors,

- (inexact) Nanoservices (API layer),

- (inexact) Device Drivers.

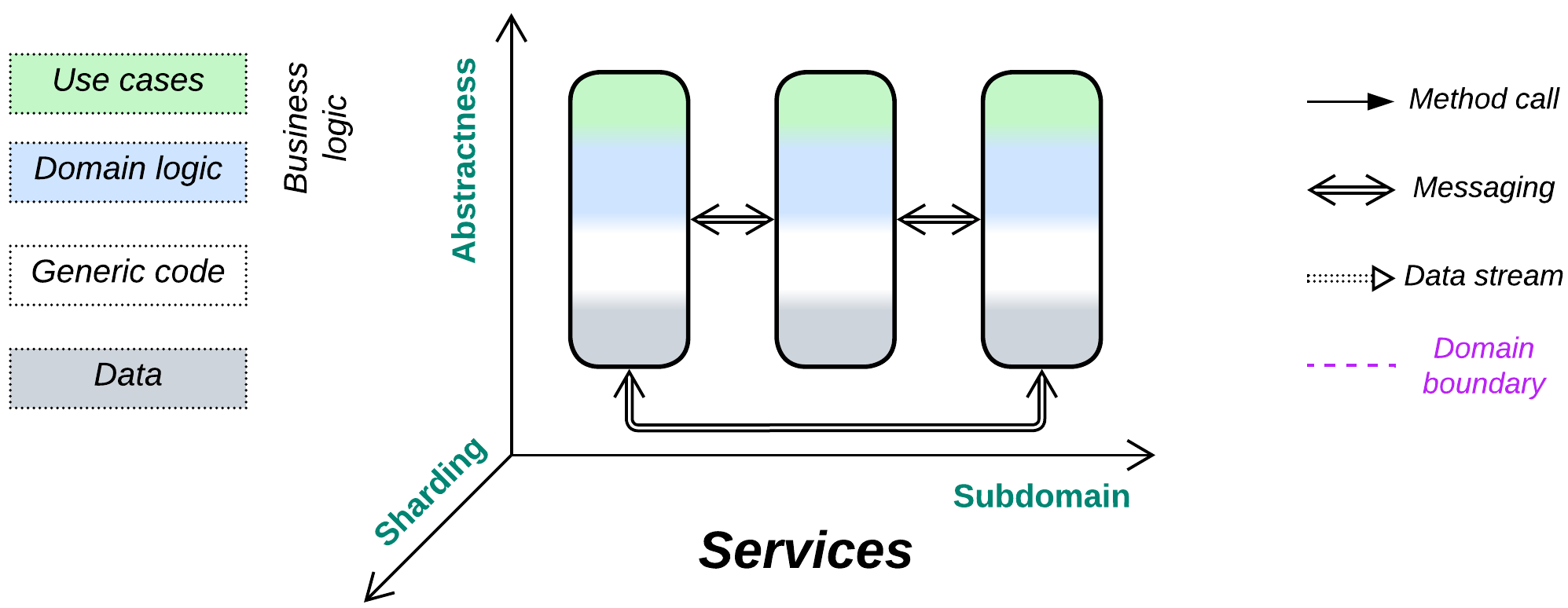

Structure: A component per subdomain.

Type: Main.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Supports large codebases | Global use cases are hard to debug |

| Multiple development teams and technologies | Poor latency in global use cases |

| Forces may vary by subdomain | No good way to share state between services |

| The domain structure should never change | |

| Operational complexity |

References: [FSA] has a chapter on Service-Based Architecture; [MP] is dedicated to Microservices.

Splitting a Monolith by subdomain allows for mostly independent properties, development, and deployment of the resulting components. However, for the system to benefit from the division, the subdomains must be loosely coupled and, ideally, of comparable size. In that case the partitioning can reduce complexity of the project’s code by cutting accidental dependencies between the subdomains. Moreover, if one of the resulting services grows unmanageably large, it can often be further partitioned by sub-subdomains to form a Cell. This flexibility is paid for through the complexity and performance of use cases which involve multiple subdomains. Another issue to remember is that boundaries between services are nearly impossible to move at later project stages as the services grow to vary in technologies and implementation styles, thus separation into services assumes perfect practical knowledge of the domain and relatively stable requirements.

Research shows that when more than five programmers work on the same subject, their performance degrades. Therefore, if we want our employees to be efficient, they should be grouped into small teams and each team should be given ownership of a dedicated component.

Performance #

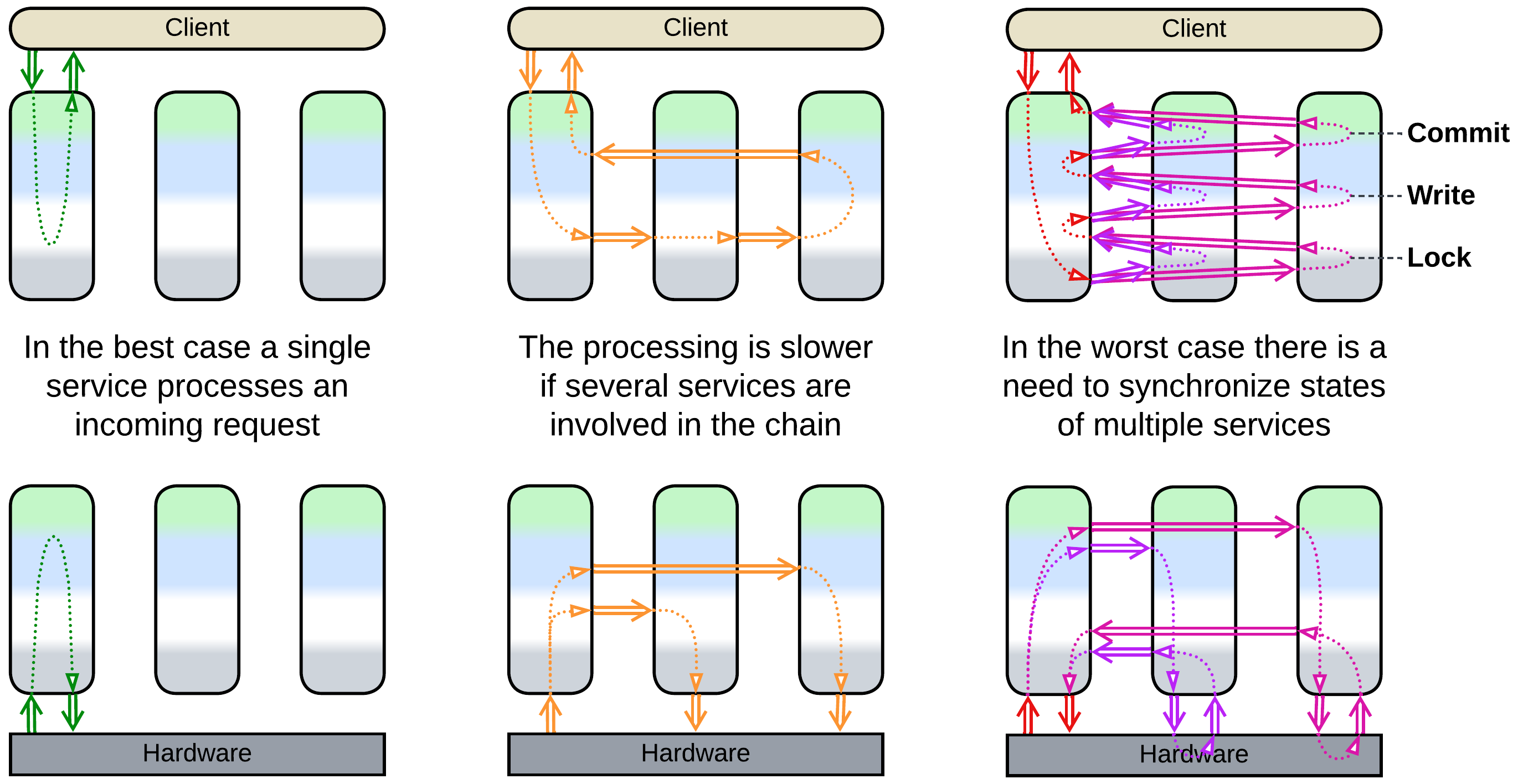

Interservice communication is relatively slow and resource-consuming, therefore it should be kept to a minimum.

The perfect case is when a single service has enough authority to answer a client’s request or process an event. That case should not be that rare as a service covers a whole subdomain while subdomains are expected to be loosely coupled (by definition).

Worse is when an event starts a chain reaction throughout the system, likely looping back a response to the original service or changing the target state of another controlled subsystem.

In the slowest scenario a service needs to synchronize its state with multiple other services, usually via locks and distributed transactions.

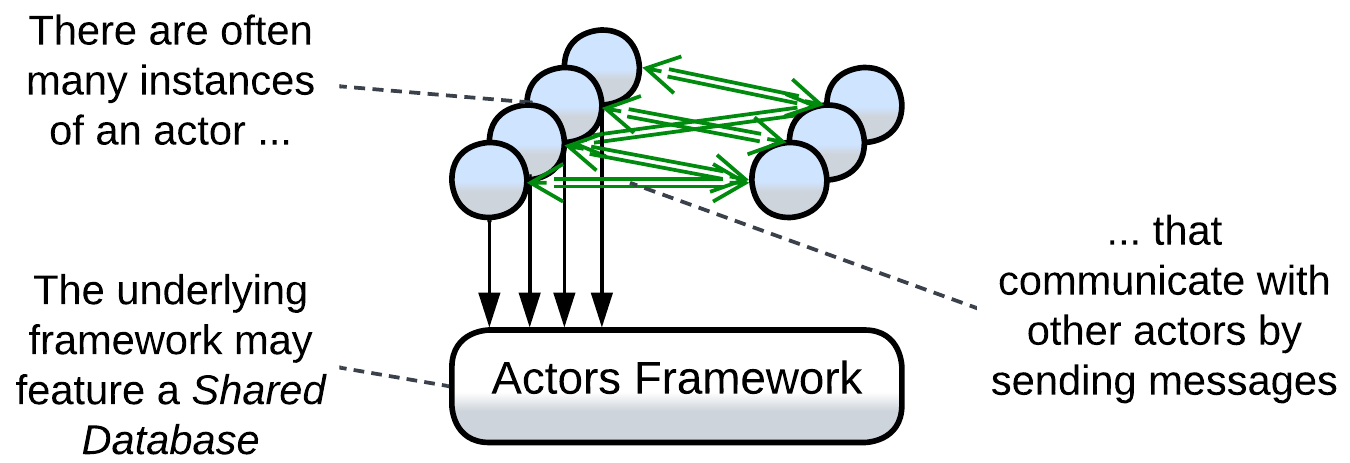

Multiple instances of an individual service may be deployed to improve throughput of the system. However, such a case will likely need a Middleware or Load Balancer to distribute interservice requests among the instances and a Shared Repository to store and synchronize any non-shardable (accessed by several instances) state.

Dependencies #

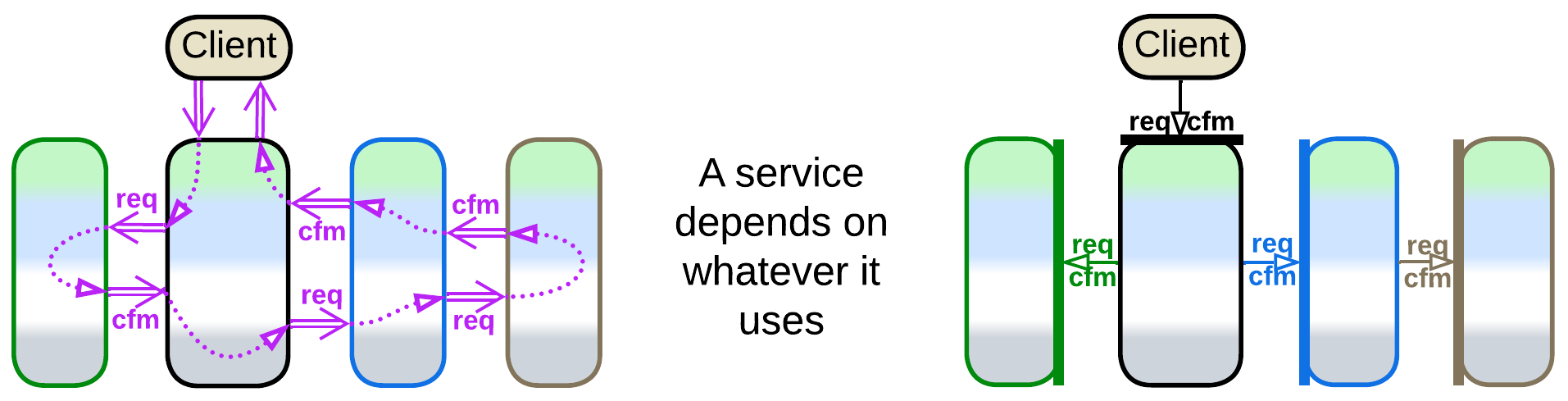

When we see a service to request help from other services and then receive the results (in a confirmation message), that service orchestrates the services it uses. Services often orchestrate each other because the subdomain a service is dedicated to is not independent of other subdomains.

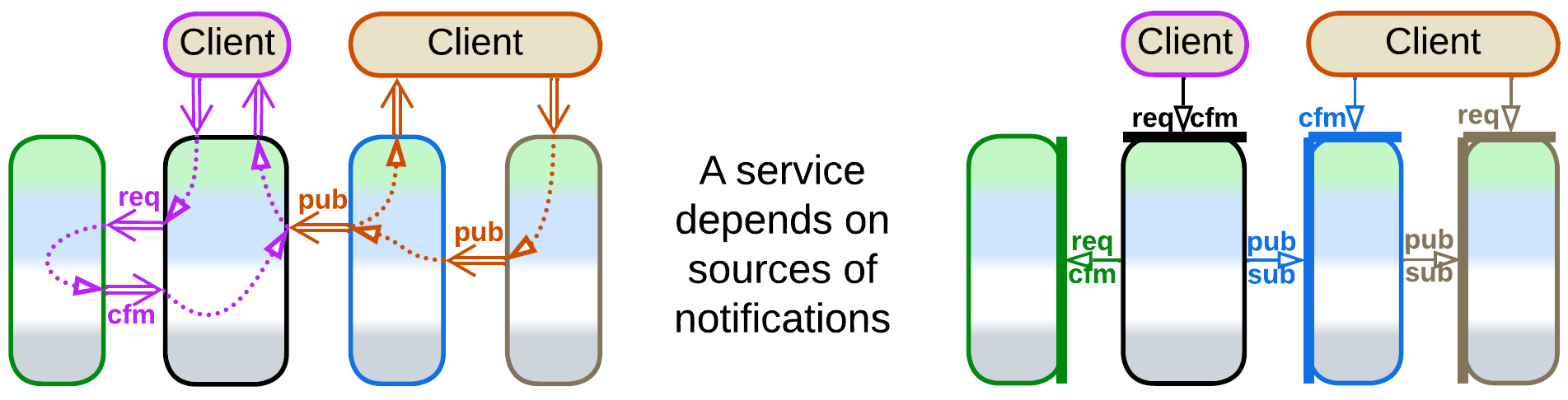

Another way for services to communicate is choreography – when a service sends a command or publishes a notification and does not expect any response. This is characteristic of Pipelines which are covered in the next chapter. Right now we should note that orchestration and choreography may be intermixed, in which case a service depends on all the services it uses or subscribes to.

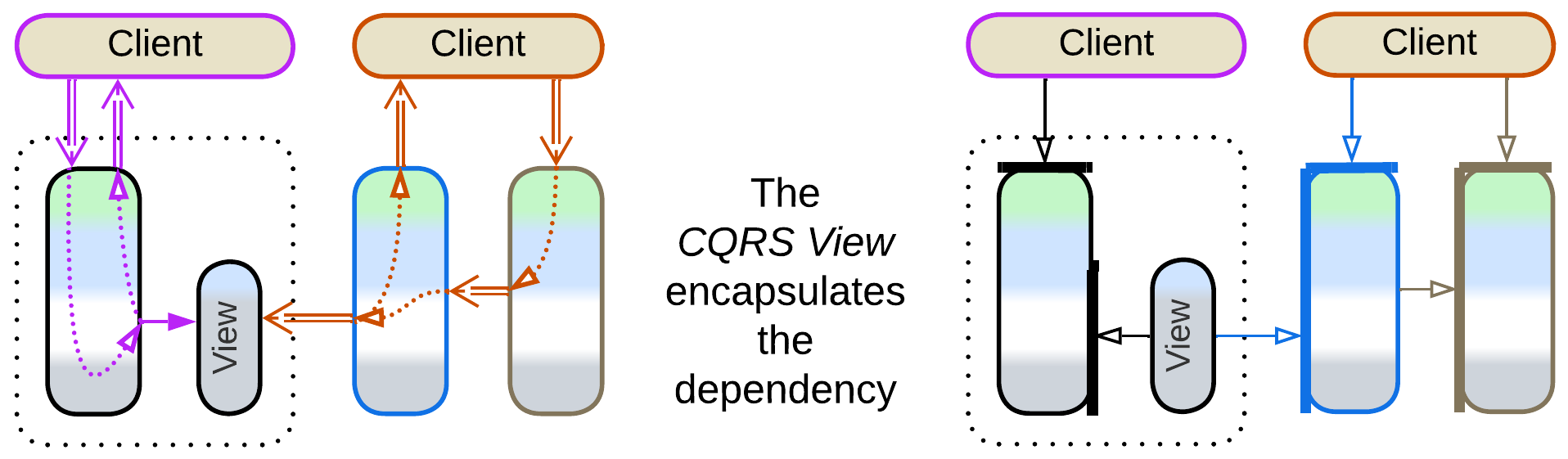

If the system relies on notifications (services publish domain events), it is possible to avoid interservice queries (pairs of a read request and confirmation with the data retrieved) by aggregating data from notifications in a CQRS (or materialized) View [MP], which can reside in memory or in a database. Views can be planted inside every service that needs data owned by other services or can be gathered into a dedicated Query Service [MP]. Though the main goal of CQRS Views is to resolve distributed joins from databases of multiple services, they also help remove dependencies in the code of services and optimize out interservice queries, simplifying APIs and improving performance. Further examples will be discussed in the chapter on Polyglot Persistence.

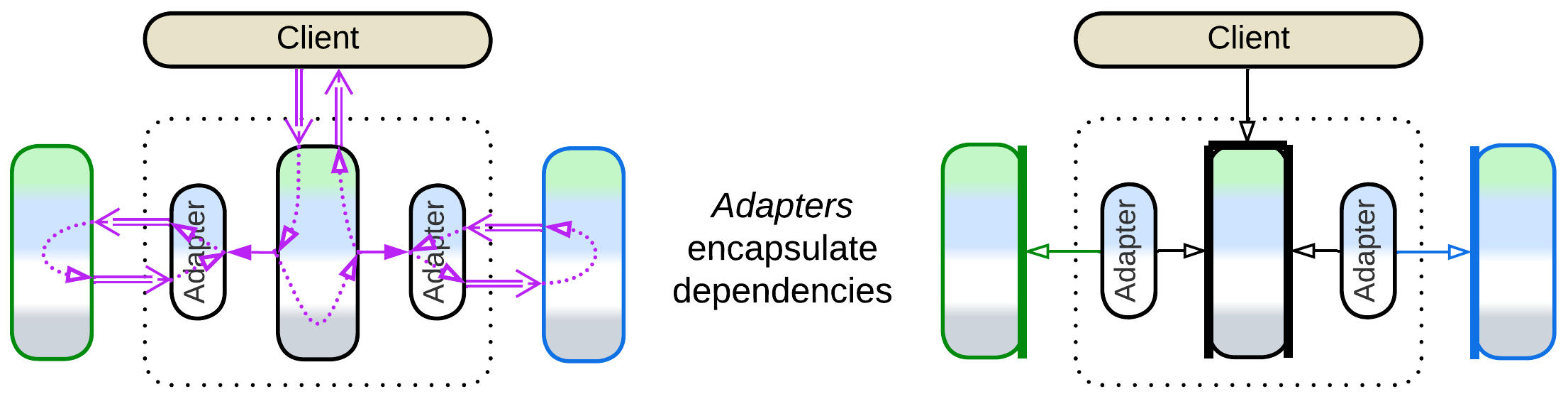

In general, a large service should wrap its dependencies with an Anticorruption Layer [DDD], following the ideas of Hexagonal Architecture. The layer consists of Adapters [GoF] between the internal domain model of the service and the APIs of the components it uses. The Adapters isolate the business logic from the external environment, granting that no change in the interface of an external service or library may ever take much work to support on the side of the team that writes our business logic as all the ensuing updates are limited to a small adapter.

Applicability #

Services are good for:

- Large projects. With multiple services developed independently, a project may grow well above 1 000 000 lines of code and still be comfortable to work on as every team needs to know only the medium-sized component it owns.

- Specialized teams. Each service would often be written and supported by a dedicated team that invests its time in learning its subdomain. This way no one needs to have a detailed knowledge of the full set of requirements, which is next to impossible in large domains.

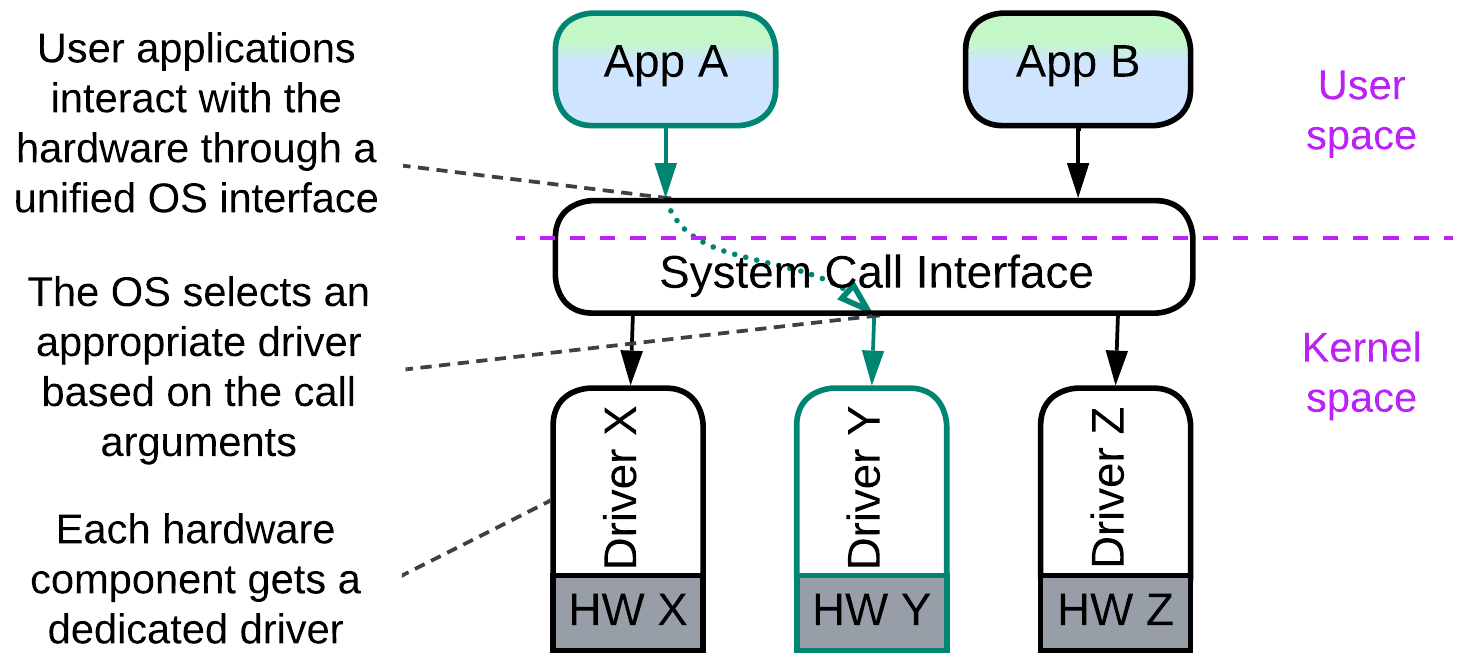

- Varied forces. In system and embedded programming, components of wildly varying behaviors need to be managed. Each of them is controlled by a dedicated service (called driver) which adapts to the specifics of the managed subsystem.

- Flexible scaling. Some services may be under more load than others. It makes sense to deploy multiple instances of heavily loaded services.

Services should be avoided in:

- Cohesive domains. If everything strongly depends on everything, any attempt to cut the knot with interfaces is going to make things worse unless the project is already dying because of its huge codebase, in which case you have nothing to lose.

- Unfamiliar domains. If you don’t understand the intricacies of the system you are going to build, you may misalign the interfaces and, by the time that the mistakes come to light, the architecture will be too hard to change [LDDD]. The coupled Services you get may actually be worse than a Monolith.

- Quick start. It takes effort to design good interfaces and contracts for Services and managing multiple deployment units is not free of trouble. Debugging will be an issue.

- Low latency. If the system as a whole needs to react to events in real time, complex services should be avoided. Nevertheless, an individual service can provide low latency for local use cases (when a single service has enough authority to react to the incoming event), wherefore simple non-blocking actors are widely used in control software.

Relations #

- Division by subdomain can be applied to Layers to form Service-Oriented Architecture (layers of services); to Proxy, Orchestrator, or API Gateway to make Backends for Frontends; to a (shared) database resulting in Polyglot Persistence.

- Services can be extended with a Proxy, Orchestrator, Middleware, or Shared Repository.

- Each service can be implemented by Layers (making a layered service), Hexagonal Architecture, or a Cell.

Variants by isolation #

Division by subdomain is so commonplace and varied that no universal terminology emerged over the years. Below is my summary, in no way complete, of several ways such systems vary. Each section lists the well-known architectures it applies to.

First and foremost, there are multiple grades between a cohesive Monolith and distributed Services. You should choose incrementally when to stop because the benefits of these next stages (color-coded below) may not outweigh their drawbacks for your project.

I review here only the most common options while a few more esoteric architectures are found in Volodymyr Pavlyshyn’s overview.

Synchronous modules: Modular Monolith (Modulith) #

The first stage to take when designing a large project is the division of the codebase into loosely coupled modules that match subdomains (bounded contexts [DDD]). If successful, that parallelizes development to a team per module while the entire application still runs in a single process, thus it stays easy to debug, the modules can share data, and any crash kills the whole system (you don’t need to take care of partial failures). You pay by establishing boundaries which will not be easy to move in the future.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Multi-team development | Subdomain boundaries are settled |

Asynchronous modules: Modular Monolith (Modulith), Embedded Actors #

The next stage is separating the modules’ execution threads and data. Each module becomes a kind of actor that communicates with other components through messaging. Now your modules don’t block each other’s execution and you can replay events at the cost of nightmarish debugging and no clean way to share data between or synchronize the state of the components.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Multi-team development | Subdomain boundaries are settled |

| Event replay | No good way to share data or synchronize state |

| Some independence of module qualities | Hard to debug |

Multiple processes #

There is also the option of running system components as separate binaries which lets them vary in technologies, allows for granular updates, and addresses stability (a web browser does not stop when one of its tabs crashes). But it adds a whole dimension of error recovery and partially executed scenarios. Moreover, divergency of technologies makes moving pieces of code between the services impossible.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Multi-team development | Subdomain boundaries are frozen |

| Event replay | No good way to share data or synchronize state |

| Independence of component qualities and technologies | Hard to debug |

| Single-component updates | Needs error recovery routines |

| Software fault isolation | Data inconsistencies after partial crashes |

| Limited granular scalability |

Distributed runtime: Function as a Service (FaaS) (including Nanoservices), Backend Actors #

Modern distributed runtimes create a virtual namespace that may be deployed on a single machine or over a network. They may redistribute running components over servers in a way to minimize network communication and may offer distributed debugging. With Actors, if one of them crashes, that generates a message to another actor which may decide on how to handle the error. The convenience of using a runtime has the dark side of vendor lock-in.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Multi-team development | Subdomain boundaries are frozen |

| Event replay | No good way to share data or synchronize state |

| Independence of component qualities |

Hard to debug |

| Single-component updates | Needs error recovery routines |

| Full fault isolation | |

| Full dynamic granular scalability | Vendor lock-in |

| Moderate communication overhead | |

| Moderate performance overhead caused by the framework |

Distributed services: Service-Based Architecture, Space-Based Architecture, Microservices #

Fully autonomous services run on dedicated servers or virtual machines. This way you employ resources of multiple servers, but the communication between them is both unstable (requests may be lost, reordered or duplicated) and slow and debugging tends to be very hard. Mesh-based (Microservices and Space-Based) architectures provide dynamic scaling under load.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Multi-team development | Subdomain boundaries are frozen |

| Event replay | No |

| Independence of component qualities and technologies | Very hard to debug |

| Single-component updates | Needs error recovery routines |

| Full fault isolation | Data inconsistencies after partial crashes |

| Full (dynamic for Mesh) granular scalability | High communication overhead |

Variants by communication #

Services also differ in the way they communicate which influences some of their properties:

Direct method calls #

When components run inside the same process and share execution threads, one component can call another. That is blazingly fast and efficient, but you should take care to protect the module’s state from simultaneous access by multiple threads (and yes, deadlocks do happen in practice). Moreover, it is hard to know what the module you call is going to call in its turn, while you are waiting on it – thus no matter how much you optimize your code, its performance depends on that of other components, often in subtle ways.

RPCs and commands (request/confirm pairs) #

If a service calls into another service or requests it to act and return results (this is how method calls are implemented in distributed systems) it has to store the state of the scenario it is executing for the duration of the call (until the confirmation message is received). That uses resources: the stored state is kept in RAM and the interruption and resumption of the execution wastes CPU cycles on context switch and on the resulting cache misses. Blocked threads are especially heavy while coroutines or fibers are more lightweight but are still not free.

Another trouble with distributed systems comes from error recovery: if your component did not receive a timely response, you don’t know if your request was (or is being, or will be) executed by its target – and you need to be really careful about possible data corruption if you retry it and it is executed twice [MP].

If a request is duplicated (as a slow network, overloaded service, or lost confirmation may cause a retry), it is important to make sure that the second (or parallel) execution of the request does not change the system’s data. This is achieved either by using idempotent logic (which is based on assignment instead of increasing or decreasing values in place), or by writing the id of the last processed message to the database (and checking that the incoming message’s id is greater than the one found in the database) [MP].

On the bright side, orchestration is human- and debugger-friendly as it keeps consecutive actions close together in the code. Therefore, synchronous interaction is the default mode of communication in many projects.

Notifications (pub/sub) and shared data #

A service may do something, publish a notification or write results to a shared datastore for other services to process, and forget about the task as it has completed its role. Choreography is resource-efficient, but you need to find and read multiple pieces of code which are spread out over several services to understand or debug the whole use case.

(inexact) No communication #

Finally, some kinds of services, namely device drivers and Nanoservices, never communicate with each other. Strictly speaking, such services don’t make a system – instead, they are isolated Monoliths which are managed by a higher-level component (OS kernel for drivers, client for Nanoservices).

Nevertheless, it is a fun fact that if the services don’t intercommunicate, the main drawbacks of the Services architecture disappear:

- There is no slow and error-prone interservice communication (they never communicate!).

- It’s not hard to debug multi-service use cases (there are no such scenarios!).

- The services don’t corrupt data on crash (there are no distributed transactions).

Variants by size #

Last but not least, the simplest classification of subdomain-separated components is by their size:

Whole subdomain: (Sub-)Domain Services #

Each Domain Service [FSA] of Service-Based Architecture [FSA] implements a whole subdomain. It is the product of the full-time work of a dedicated team. A project is unlikely to have more than 10 of such services (in part because the number of top-level subdomains in any domain is usually limited).

Part of a subdomain: Microservices #

Microservices enthusiasts estimate the best size of a component of their architecture to be below a month of development by a single team. That allows for a complete rewrite instead of refactoring in case the requirements change. When a team completes one microservice it can start working on another, probably related, one while still maintaining its previous work. A project is likely to contain from tens to few hundreds of microservices.

Class-like: Actors #

An actor is an object with a message-based interface. They are used correspondingly. Though the size of an actor may vary, as does the size of an OOP class, it is still very likely to be written by a single programmer.

Single function: FaaS, Nanoservices #

A nanoservice is a single function (FaaS [DDS]) usually deployed to a serverless provider. Nanoservices are used as API method handlers or as building blocks for Pipelines.

Variants by internal structure #

A service is not necessarily monolithic inside. Because a service is encapsulated from its users by its interface, it can have any kind of internal structure. The most common cases, which can be intermixed together, are:

Monolithic service #

A monolithic service is a service with no definite internal structure, probably small enough to allow for complete rewrite instead of refactoring – the ideal of proponents of Microservices. It is simple & stupid to implement but relies on external sources of persistent data. For example, device drivers and Actors usually get their (persisted) configuration during initialization. A monolithic backend service may receive all the data it needs in incoming requests, via a query to another service, or by reading it from a Shared Database.

Layered service #

A layered service is divided into layers. This approach is very common both with backend (micro-)services, where at least the database is separated from the business logic, and with device drivers in system programming, where hardware-specific low-level interrupt handlers and register access are separated from the main logic and high-level OS interface.

Layering provides all of the benefits from the Layers pattern, including support for conflicting forces, which may manifest, for example, as the ability to deploy the database to a dedicated server in backend or as a very low latency in the hardware-facing layer of a device driver.

Another benefit comes from the existence of the upper integration layer which may orchestrate interactions with other services, isolating the lower layers from external dependencies.

Hexagonal service #

A hexagonal service has its external dependencies isolated behind vendor-agnostic interfaces.

This is a real-world application of Hexagonal Architecture which both ensures that the business logic does not depend on specific technologies and protects from vendor lock-in. It is highly recommended for long-lived projects.

Scaled service #

With scaled services there are multiple instances of a service. In most cases they share a database (though sometimes the database may be sharded or replicated together with the service that uses it) and get their requests through a Load Balancer or Sharding Proxy.

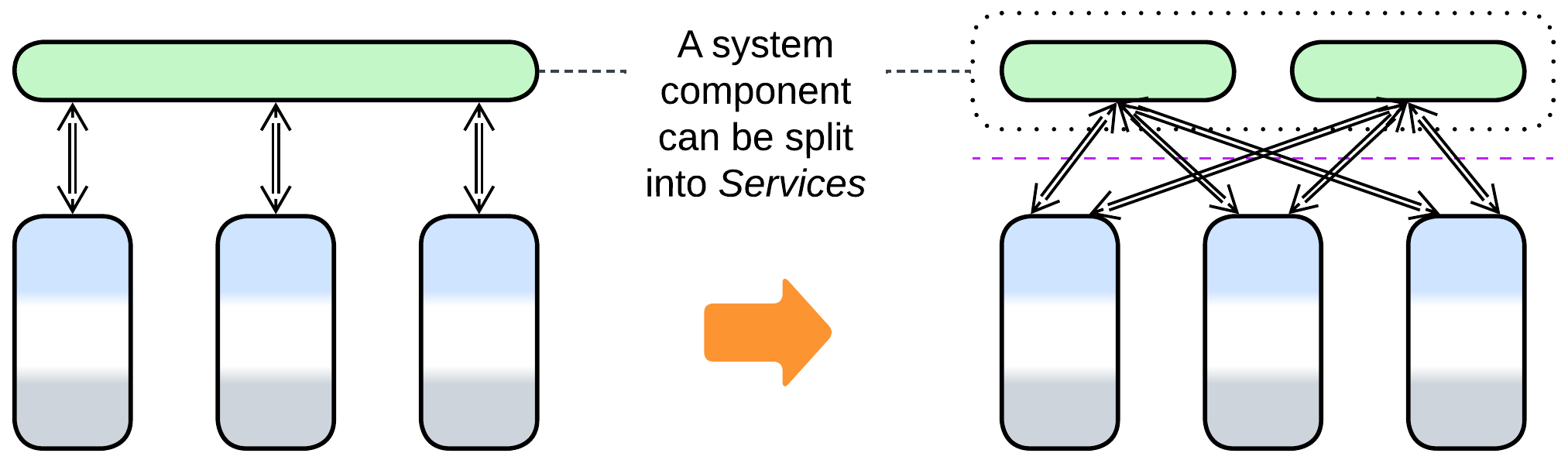

Cell (WSO2 definition) (service of services), Domain (Uber definition), Cluster #

When a service is split into a set of subservices, it makes a Cell (WSO2 name), Domain (Uber name), or Cluster [DEDS]. All the incoming communication passes through a Cell Gateway which encapsulates the Cell from its environment. Outgoing communication may involve the Cell Gateway or dedicated Adapters (Anticorruption Layer [DDD]) A Cell may deploy its own Middleware and/or share a database among its components.

Cell-Based Architecture (according to WSO2, as opposed to Amazon’s alias for Shards) appears when there is a need to recursively split a service, either because it grew too large or because it makes sense to use several incompatible technologies for its parts. It may also be applied to group services if there are too many of them in the system.

Domain-Oriented Microservice Architecture (DOMA) is a SOA-style layered system of Cells.

Examples #

Services are pervasive among advanced architectures which either build around a layer of services that contains the bulk of the business logic (Proxy, Orchestrator, Middleware and Shared Repository) or use small services as an extension of the main monolithic component (PlugIns and Hexagonal Architecture). Polyglot Persistence, Backends for Frontends and Service-Oriented Architecture go all out partitioning the system into interconnected layers of services. Hierarchy and Mesh require the services to implement or use a polymorphic interface to simplify the components that manage them.

Examples of Services include:

Service-Based Architecture #

This is the simplest use of Services where each subdomain gets a dedicated component. A Service-Based Architecture [FSA] tends to consist of a few coarse-grained services, some of which may share a database and have little direct communication. An API Gateway is often present as well.

Microservices #

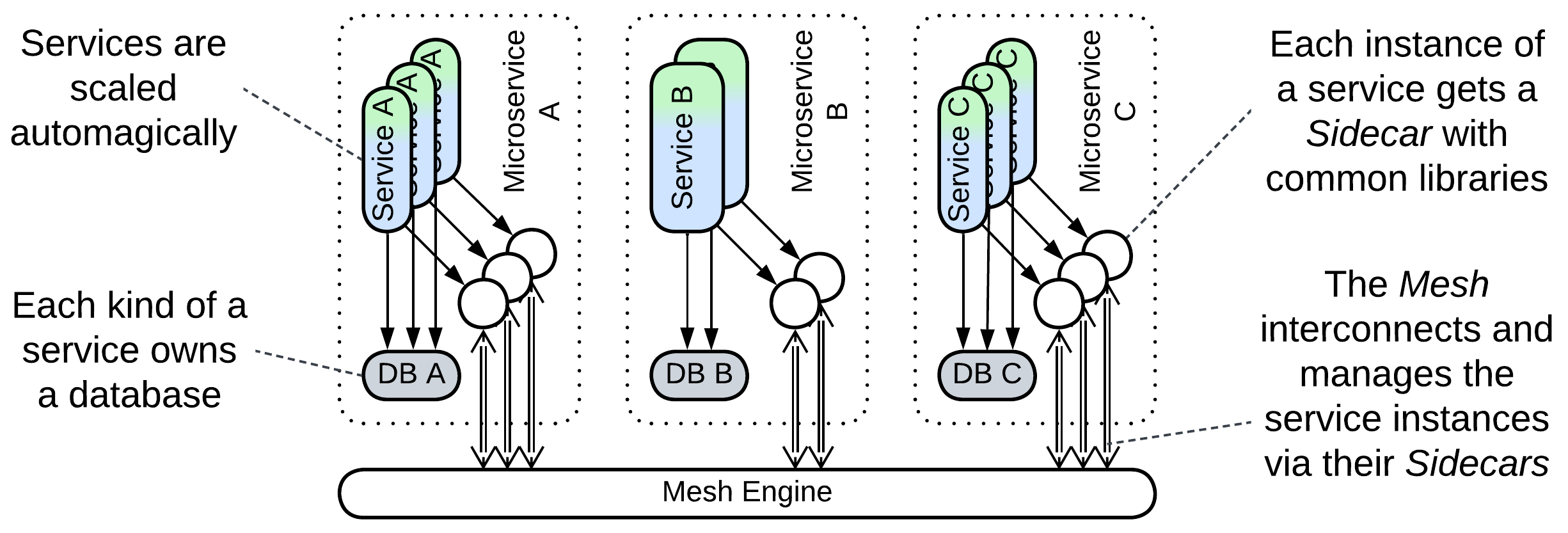

Microservices [MP, FSA] are usually smaller than components of Service-Based Architecture and feature multiple services per subdomain with strict decoupling: no Shared Database, independent (and often dynamic) scaling and deployment. Even orchestration and distributed transactions (Sagas) are considered to be a smell of bad design.

Microservices fit loosely coupled domains with parts which vary drastically in both forces and technologies. Any attempt to use them for an unfamiliar domain is calling for trouble. Some authors insist that the “micro-” means that a microservice should not be larger in scope than a couple of weeks of work for a programming team. That allows rewriting one from scratch instead of refactoring. Others assert that too high a granularity makes everything overcomplicated. Such a diversity of opinions may mean that the applicability and the very definition of Microservices varies from domain to domain.

This architecture usually relies on a Service Mesh for Middleware where common functionality, like logging, is implemented in co-located Sidecars [DDS]. A layer of Orchestrators (called Integration Microservices) may be present, resulting in Cell-Based Architecture or Backends for Frontends.

Dynamically scaled Pools of service instances are common thanks to the elasticity of hosting in a cloud. Extreme elasticity requires Space-Based Architecture, which puts a distributed in-memory database node in each Sidecar.

Some authors distinguish between architectural patterns and architecture styles (architectures) [FSA, MP]. The difference is similar to that between libraries and frameworks: you use a library or pattern (e.g. division of a component into Layers or Services) when you think that it will help your needs, but you build your entire system according to the rules of a framework or style (such as Microservices or Enterprise SOA). This book does not accent that difference – instead, it boils down styles to combinations of patterns.

Actors #

An actor is an entity with private data and a public message queue. They are like objects with the difference that actors communicate only by sending each other asynchronous messages. The fact that a single execution thread may serve thousands of actors makes actor systems an extremely lightweight approach to asynchronous programming. As an actor is usually single-threaded, there is no place for mutexes and deadlocks in the code and it is possible to replay events. Non-blocking Proactors are often used in real-time systems.

Actors have long been used in telephony (which is the domain where real-time communication meets complex logic and low resources) and with the invention of distributed runtime environments (e.g. Erlang/OTP or Akka) they found their place in messengers and banking which need to interconnect millions of users while providing personalized experience and history for everyone. Every user gets an actor that represents them in the system by communicating both with other actors (forming a kind of Mesh) and with the user’s client application(s).

If we apply a bit of generalization, we can deduce that any server or backend service is an actor because its data cannot be accessed from outside and asynchronous IP packets are its only means of communication. Services of Event-Driven Architecture closely match this definition.

A deadlock happens when several threads in a system wait for each other to release unique resources they have each taken. As no thread involved in the deadlock can continue its operation, the system cannot complete its task. A single-threaded actor cannot deadlock because it does not contain multiple threads in the first place.

(inexact) Nanoservices (API layer) #

Though Nanoservices are defined by their size (a single function), not system topology, I want to mention a specific application from Diego Zanon’s book Building Serverless Web Applications. That example is interesting because it comprises a single layer of isolated functions (each providing a single API method) which may share functionality by including code from a common repository. As nanoservices of this kind never interact, the common drawbacks of Services (poor debugging and high latency) don’t apply to them.

(inexact) Device Drivers #

An operating system must run efficiently with an unpredictable combination of hardware components, any of which can come from different manufacturers. It is impossible to know all the combinations beforehand. Thus it employs one service (called driver) per hardware device. A driver adapts a manufacturer- and model-specific hardware interface to the generic interface of the OS kernel, allowing for the kernel to operate the hardware it controls without the detailed knowledge of the model. Internally, a driver is usually layered:

- The lowest layer, called the Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL), provides a model-independent interface for a whole family of devices from a manufacturer.

- The next layer of a driver is likely to contain manufacturer-specific algorithms for efficient use of the hardware.

- The third layer, if present, is probably busy with high-level tasks which are common for all devices of the given type and may be implemented by the kernel programmers.

The whole system of kernel, drivers, and user applications comprises the Microkernel architecture which bridges resource consumers and resource providers. As the drivers don’t need to coordinate themselves (this is done by the kernel), they don’t really make a system of Services and thus don’t have the corresponding drawbacks.

Evolutions #

Services are subject to a wide array of evolutions, just like the other basic metapatterns. These are summarized below and detailed in Appendix E.

Evolutions that add or remove services #

Services work well when each service matches a subdomain and is developed by a single team. If those premises change, you’ll need to restructure the services:

- A new feature request may emerge outside of any of the existing subdomains, creating a new service, or a service may grow too large to be developed by a single team, calling for division.

- Two services may become so strongly coupled that they fare better if merged together, or the entire system may need to be glued back into a Monolith if the domain knowledge changes or if interservice communication strongly degrades performance.

Evolutions that add layers #

The most common modifications of a system of Services involve supplementary system-wide layers which compensate for the inability of the services to share anything among themselves:

- A Middleware tracks all the deployed service instances. It mediates the communication between them and may manage their scaling and failure recovery.

- Sidecars [DDS] of a Service Mesh make a virtual layer of shared libraries for the Microservices it hosts.

- A Shared Database simplifies the initial phases of development and interservice communication and enables the use of Services in data-centric domains.

- Proxies stand between the system and its clients and take care of shared aspects that otherwise would need to be implemented by every service.

- An Orchestrator is the single place where the high-level logic of all use cases resides.

Those layers may also be consolidated into Combined Components:

- Message Bus is a type of Middleware that supports multiple protocols.

- API Gateway combines Gateway (a kind of Proxy) and Orchestrator.

- Event Mediator is an orchestrating Middleware.

- Shared Event Store combines Middleware and Shared Repository.

- Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) is an orchestrating Message Bus.

- Space-Based Architecture employs all four layers: Gateway, Orchestrator, Shared Repository, and Middleware.

Evolutions of individual services #

Each service starts as either a Monolith or as Layers and may undergo the corresponding evolutions:

- Layers help to reuse third-party components (e.g. a database), organize the code, support conflicting forces and the upper layer of the service may orchestrate other services.

- A Cell is a service which is subdivided into several services that share an API Gateway and may share a database and/or a Middleware. All of the components of a Cell are usually deployed together. That helps when dealing with overgrown services without increasing the operational complexity of the system – but only if the Cell’s components are loosely coupled.

- A service may use a Load Balancer or a load balancing Middleware to scale. Its instances usually rely on a Shared Database for persistence.

- Polyglot Persistence or CQRS may be used inside a service to improve the performance of its data layer.

- CQRS Views [MP] or a Query Service [MP] help reconstruct the state of other services from event sourcing.

- Hexagonal Architecture isolates the business logic of the service from external dependencies.

- In rare cases Plugins or Scripts help to vary the behavior of a service.

Summary #

Services deal with large projects by dividing them into subdomain-aligned components of smaller sizes which can be handled by dedicated teams. These may vary in technologies and quality attributes. However, services have a hard time cooperating in anything, from sharing data to debugging, and come with an innate performance penalty. There are a few options halfway between Monolith and Distributed Services that have milder benefits and drawbacks.