Monolith #

Let’s take a look at the simplest possible metapattern – Monolith – and see what it can teach us.

Keep it simple, stupid! If you don’t need a modular design, why bother?

Known as: Monolith.

Variants:

By internal structure:

- True Monolith / Big Ball of Mud,

- (misapplied) Layered Monolith [FSA],

- (misapplied) Modular Monolith [FSA] (Modulith),

- (inexact) Plugins [FSA] and Hexagonal Architecture.

By mode of action:

- Reactor [POSA2],

- Proactor [POSA2],

- (inexact) Half-Sync/Half-Async [POSA2],

- (inexact) (Re)Actor-with-Extractors.

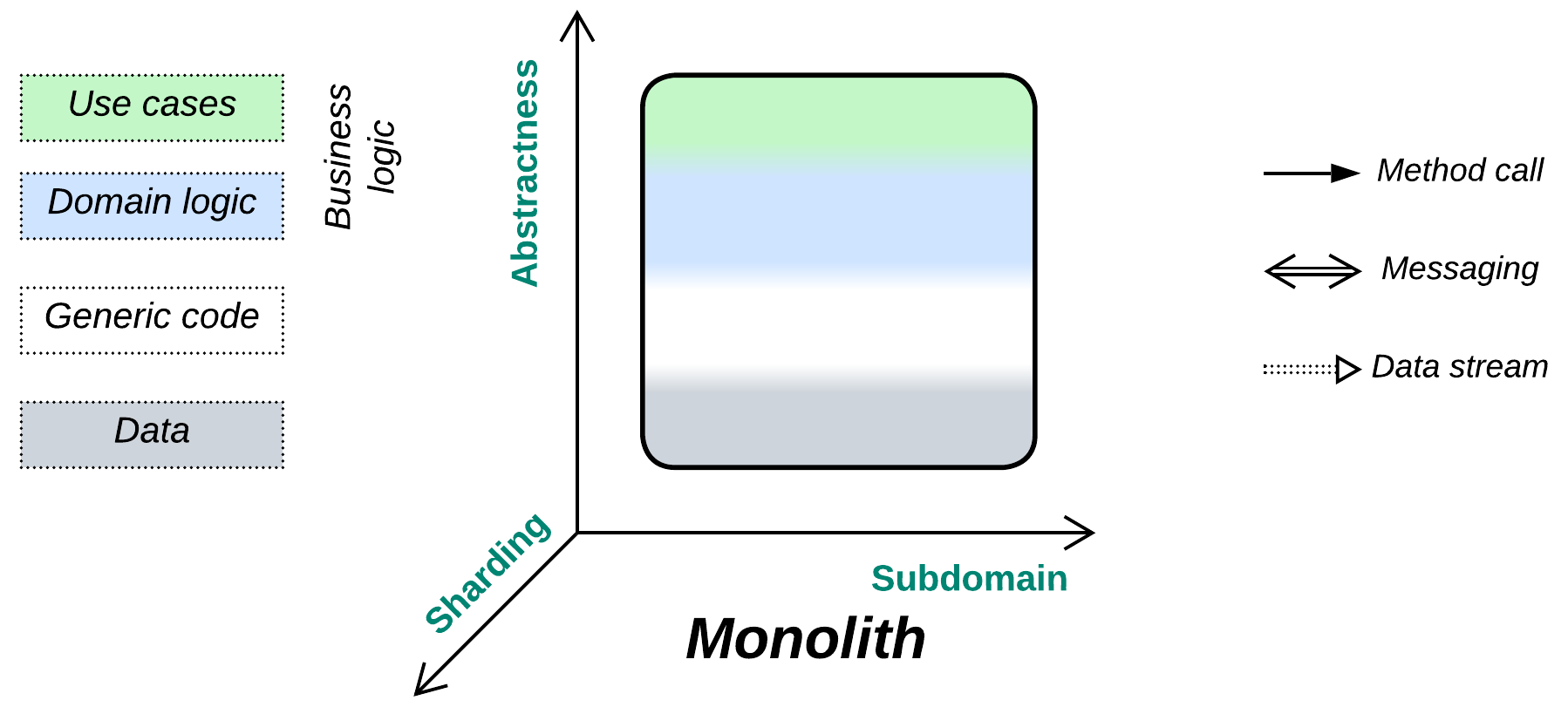

Structure: A monoblock with no strong internal modularity.

Type: Main, root of the hierarchy of metapatterns.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Rapid start of development | Quickly deteriorates with project growth |

| Easy debugging | Hard to develop with multiple teams |

| Best latency | Does not scale |

| Low resource consumption | Lacks support for conflicting forces |

| The system’s state is self-consistent | Any failure crashes the entire system |

References: Big Ball of Mud for a philosophical discussion, my article and [POSA2] for subtypes of Monolith, Martin Fowler’s discussion on starting development with Monolith, [MP] for the definition of monolithic hell and a post describing the first-hand experience of it.

We distance ourselves from the systems architecture’s definition of Monolith as a single unit of deployment because our main focus lies with the internal structure of systems. Instead, we will use the old definition of a monolithic application as a cohesive lump of code containing no discernible components [GoF, POSA1].

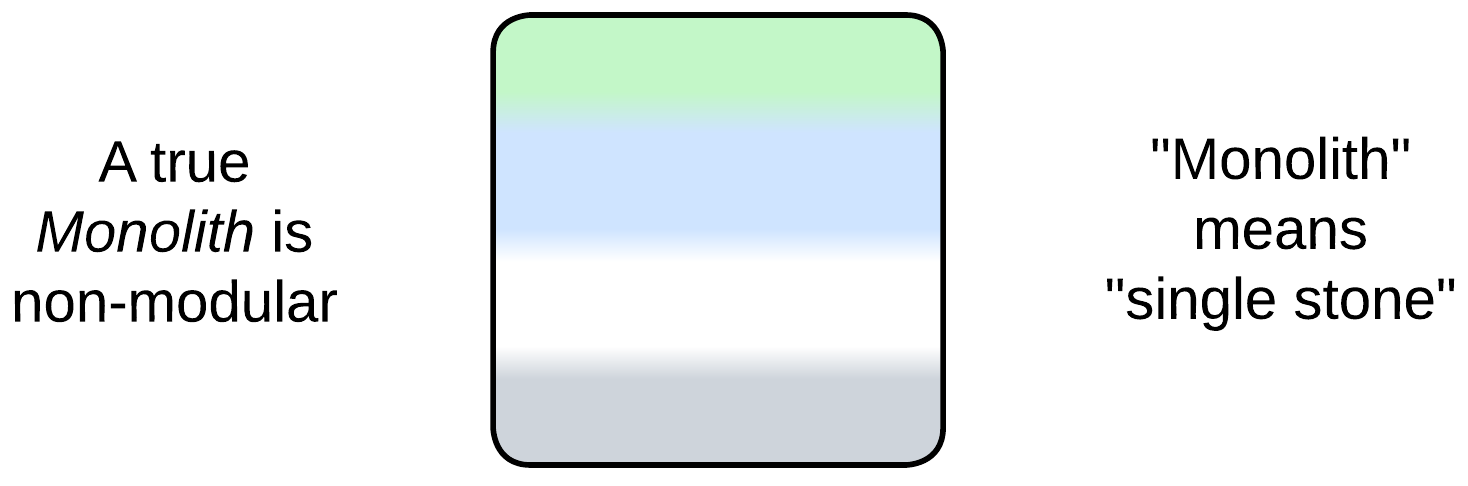

A Monolith is non-modular (not divided by interfaces) along all the structural dimensions. Its thorough cohesiveness is both its blessing (single-step debugging, system-wide optimizations) and its curse (messy code, no scalability of development and deployment, zero flexibility).

Performance #

On one hand, monolithic applications provide perfect opportunities for performance optimizations as every piece of code is readily accessible from any other. On the other hand, if the application is stateful, access to the state may limit the performance benefit of using multiple CPU cores. Furthermore, large Monoliths may become too messy for programmers to identify and too complicated and fragile to implement any non-local optimizations that could drastically improve performance.

There are many kinds of bottlenecks which limit an application’s performance. As soon as you change your code to use multiple CPU cores you may find that the program’s throughput is constrained by the speed of your hard drive or network interface. And when you upgrade those two, you may well hit something more subtle, like OS interrupts or CPU cache coherence.

Overall, tiny Monoliths provide the best latency and throughput per CPU core. Larger performance-critical projects may need to partition the code into Layers or Services so that any manually optimized part remains small enough to be manageable. Higher throughput is attainable through distributing the software over multiple computers: Shards employ several copies of the whole system while a Pipeline may run each step of data processing on a separate server.

Dependencies #

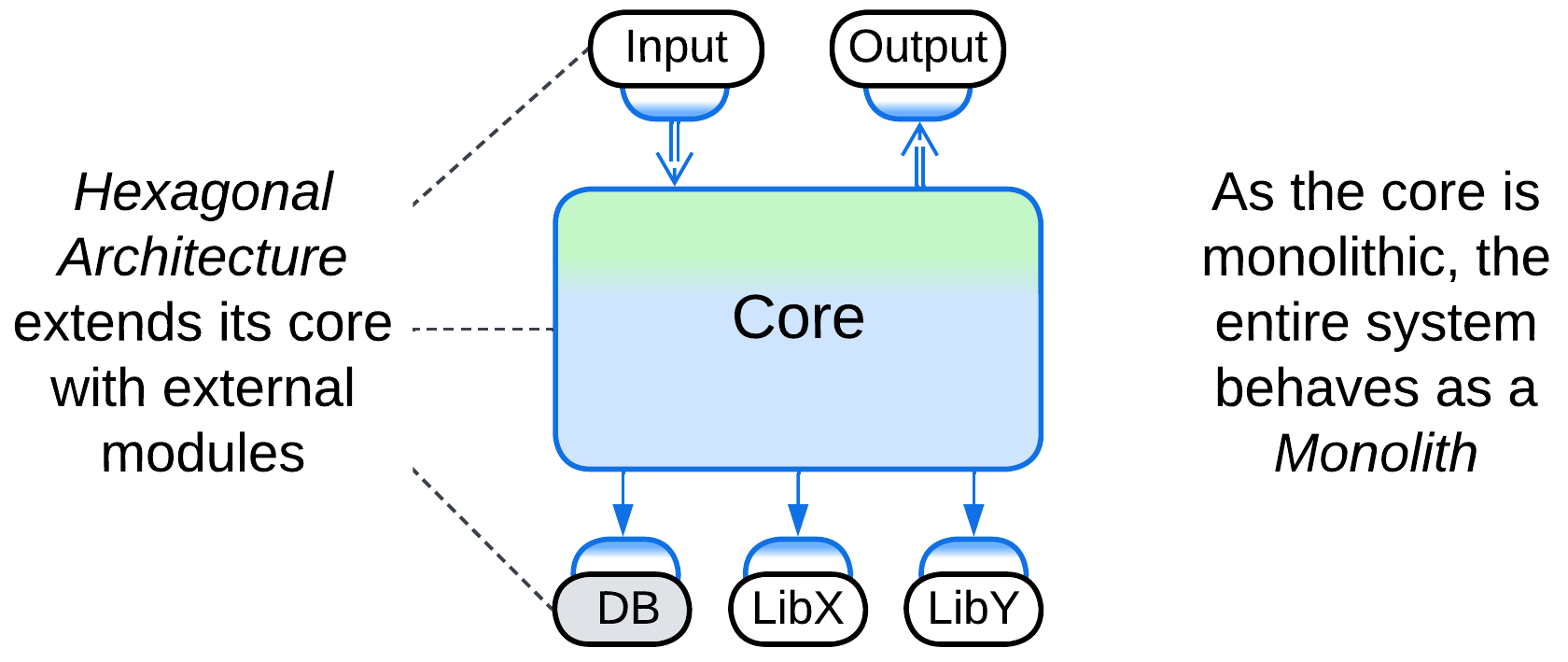

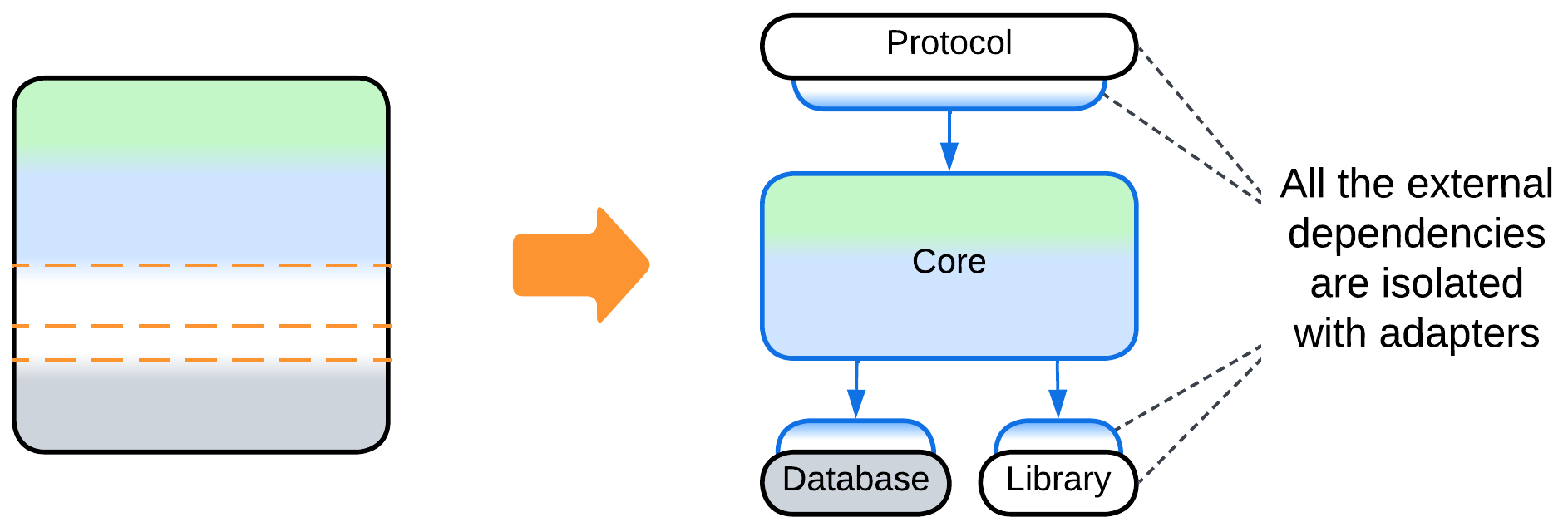

Even though a Monolith is a single module, meaning that there are no dependencies among its parts (in fact, everything depends on everything), it still may depend on some external components or services which it uses. Those dependencies tend to cause vendor lock-in or make the software OS- or hardware-dependent. Hexagonal Architecture (including MVP and MVC) decouples a monolithic implementation from its dependencies by isolating the latter behind Adapters.

Applicability #

Monolith is good for cases which are harmed by the introduction of modularity:

- Tiny projects. The project is relatively small (below 10 000 lines) and the requirements will never change (e.g. you need to implement an application for running a specific mathematical calculation or a library supporting a well-established communication protocol).

- Ultra optimization. You already have a working and thoroughly optimized system, but you still need that extra 5% performance improvement achievable through merging all the components together.

- Low latency. If you need ultra low latency for the entire application, any asynchronous communication between its modules is not a viable option. Example: high-frequency trading.

- Prototyping. You are writing a prototype in a domain you are not familiar with, gathering requirements in the process. Chances for a correct initial identification of weakly coupled subdomains (to become modules or services) are quite low and it is worse to have wrong module boundaries than to use no modules at all. At the later stages of the project, when you will know the domain much better and your users will have approved the initial implementation, you will be able to split the system into components in a much better way, if and when that will be needed. Nevertheless, you may already know enough to apply Layers or Hexagonal Architecture which keep the business logic monolithic while isolating it from the periphery and third-party libraries.

- Quick and dirty. You are out of time and money and need to show your customers something right now. There is no time to think, no money to perfect the code, and no day after tomorrow.

Monolith should be avoided when we need modules:

- Incompatible forces. There are conflicting forces (non-functional requirements) for different subsets of functionality. They require splitting the system into (usually asynchronous) components each of which is specifically designed to satisfy its own subset of forces. Your main tool is the careful selection of appropriate technologies and architectures on a per component basis which may allow the project to satisfy all the non-functional requirements even if the task looks impossible during the initial analysis.

- Long-running projects. The project is going to evolve over time and you believe you can predict the general direction of the future changes. Modularity brings flexibility which you will need for sure.

- Larger codebases. The project grows above average size (100 000 lines of code). If you don’t split it into smaller components it will grow into a monolithic hell with development and debugging slowing down year after year till it reaches terminal stage. Slow development is a waste of money, both in salary and in time to market.

- Multiple teams. You have multiple teams to work on the project. Inter-team communication is hard and error-prone whereas merging several teams together is known to greatly reduce the programmers’ productivity (which peaks with teams of 5 or less members). Explicit interfaces between components will formalize interdependencies between the teams, lowering communication overhead.

- Fault tolerance. Your domain requires fault tolerance which is next to impossible for large monolithic applications.

- Resource-limited. Your project is too resource-hungry for commodity hardware. Even if you buy the best server for its needs right now, it is going to crave more tomorrow (or on the next Black Friday).

- Distributed setup. Your project needs to run on multiple hardware devices. One of common examples is a web service containing frontend and backend.

Relations #

Monolith:

- Can be extended with a Proxy, or turned into a Hexagonal Architecture or Plugins.

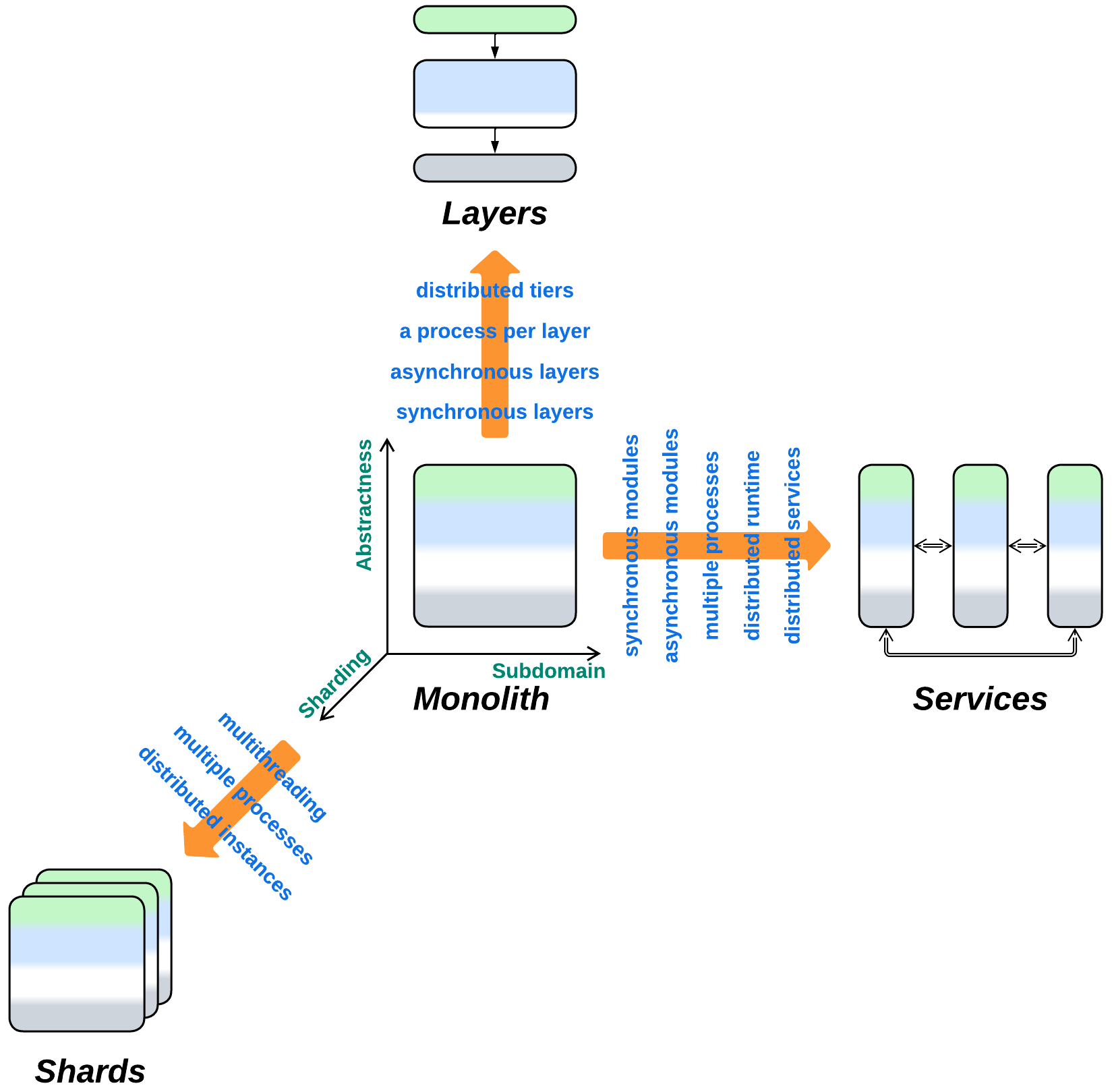

- Yields Layers, Services, or Shards if divided along the abstractness, subdomain, or sharding dimensions, correspondingly. All the known architectures are combinations of those three metapatterns.

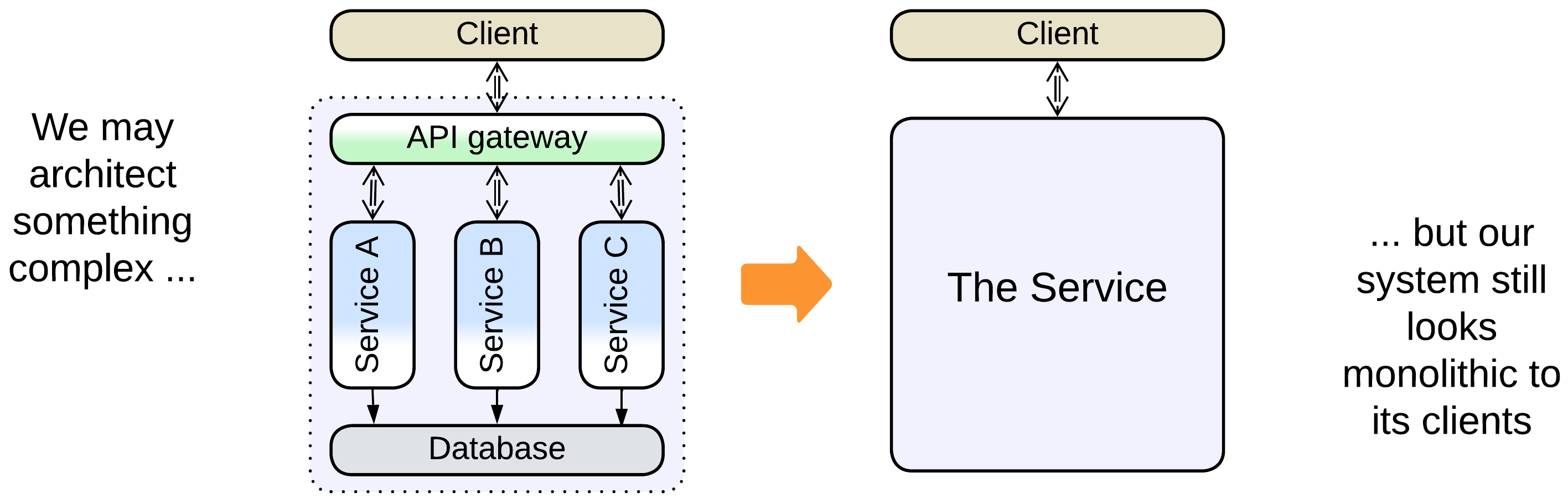

- Is the bird’s-eye view of any architecture.

Variants by the internal structure #

Monoliths are the atoms to create more complex architectures from, the opaque building blocks, each of which satisfies a consistent set of forces. Any individual component of a more complex architecture either is monolithic or encapsulates another architectural pattern, decomposable into Monoliths, and any architecture looks monolithic to its clients.

There is a misunderstanding because software architecture inspects the internals of applications at the level of modules or even classes while systems architecture deals with distributed systems and operates deployment units which tend to incorporate multiple modules or even applications. Each branch of the architecture calls its atomic unit a Monolith, leading to the term sticking both to a module that cannot be subdivided, as in [GoF] and [POSA1], and to a (sub)system which must be deployed together, as in present-day literature.

As we aspire to build a unified classification for both distributed and local systems, we must treat both kinds of components in the same way, whether they are distributed services, co-located Actors, or in-process modules. Thus, for the scope of the current book, we will follow the definition of Monolith from [GoF]: “Tight coupling leads to monolithic systems, where you can’t change or remove a class without understanding and changing many other classes”. Still, we need to account for a couple of misnomers from system architecture.

True Monolith, Big Ball of Mud #

A true Monolith features no clear internal structure. If it has any components, they are so tightly coupled that the entire thing behaves as a single cohesive module. This is what we explore in the current chapter.

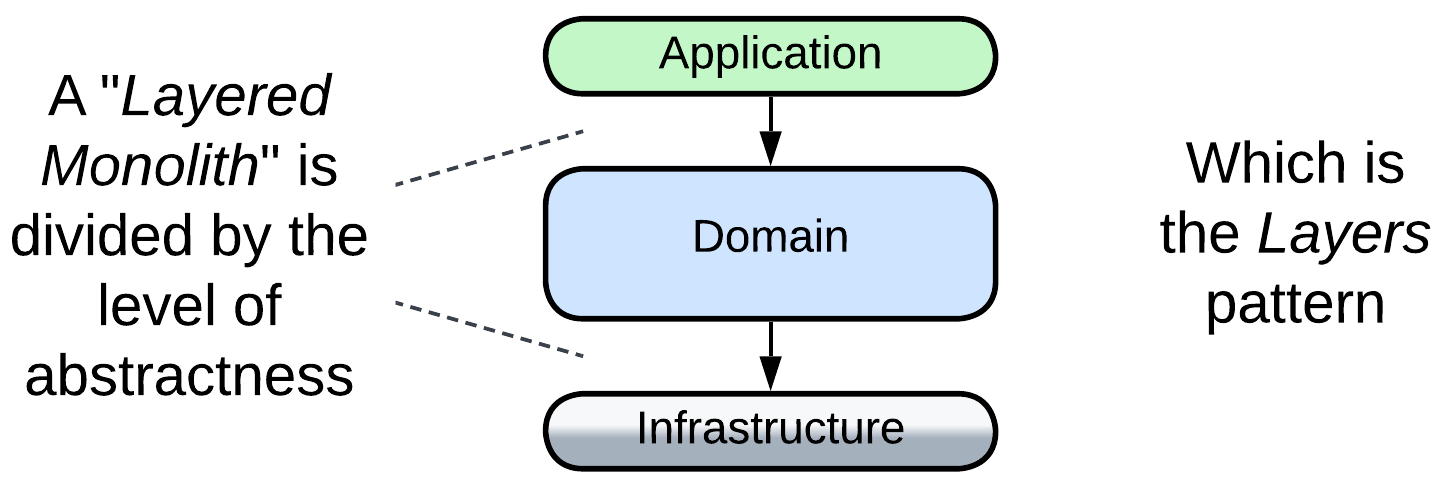

(misapplied) Layered Monolith #

When they say Layered Monolith [FSA], that refers to a non-distributed application with a layered structure, which is a proper Layers architecture and will be discussed in the corresponding chapter. It is called a Monolith for the sole reason that it is not distributed. Nevertheless, Layers resemble Monolith in many aspects, including easy debugging and the risk of outgrowing the comfort zone of developers.

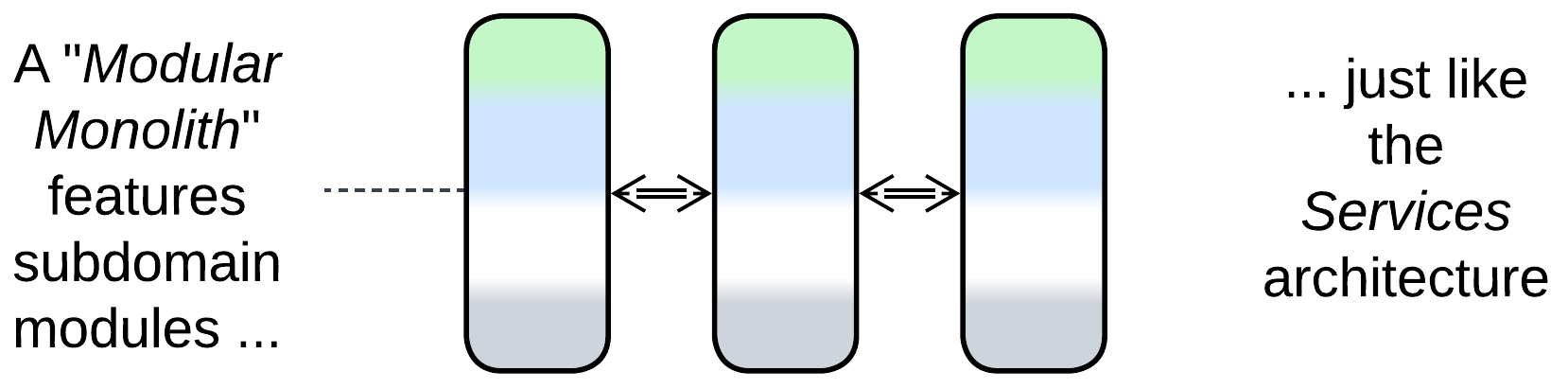

(misapplied) Modular Monolith (Modulith) #

A Modular Monolith (Modulith) [FSA] is a single-process application subdivided into modules that correspond to subdomains. If the modules communicate via in-process messaging, the architecture is nearly identical to coarse-grained Actors, thus it is a Monolith only in name. Modulith is a kind of Services – it supports development by multiple teams and the asynchronous variant is hard to debug. The relation to Monolith is mostly limited to the inability to scale individual parts of the system.

(inexact) Plugins and Hexagonal Architecture #

Plugins [FSA] and Hexagonal Architecture extend a (sub)system with external components. These architectures can be applied to a Monolith without drastically changing its properties – it still remains relatively easy to write and debug but hard to support when outgrown. Therefore, we will not currently discuss these modifications, mainly because each of them has a dedicated chapter.

Variants by the mode of action #

Let’s take a look inside a Monolith.

Any software module reacts to incoming events or data and produces outgoing events or data. But there are a few basic ways to implement that cycle:

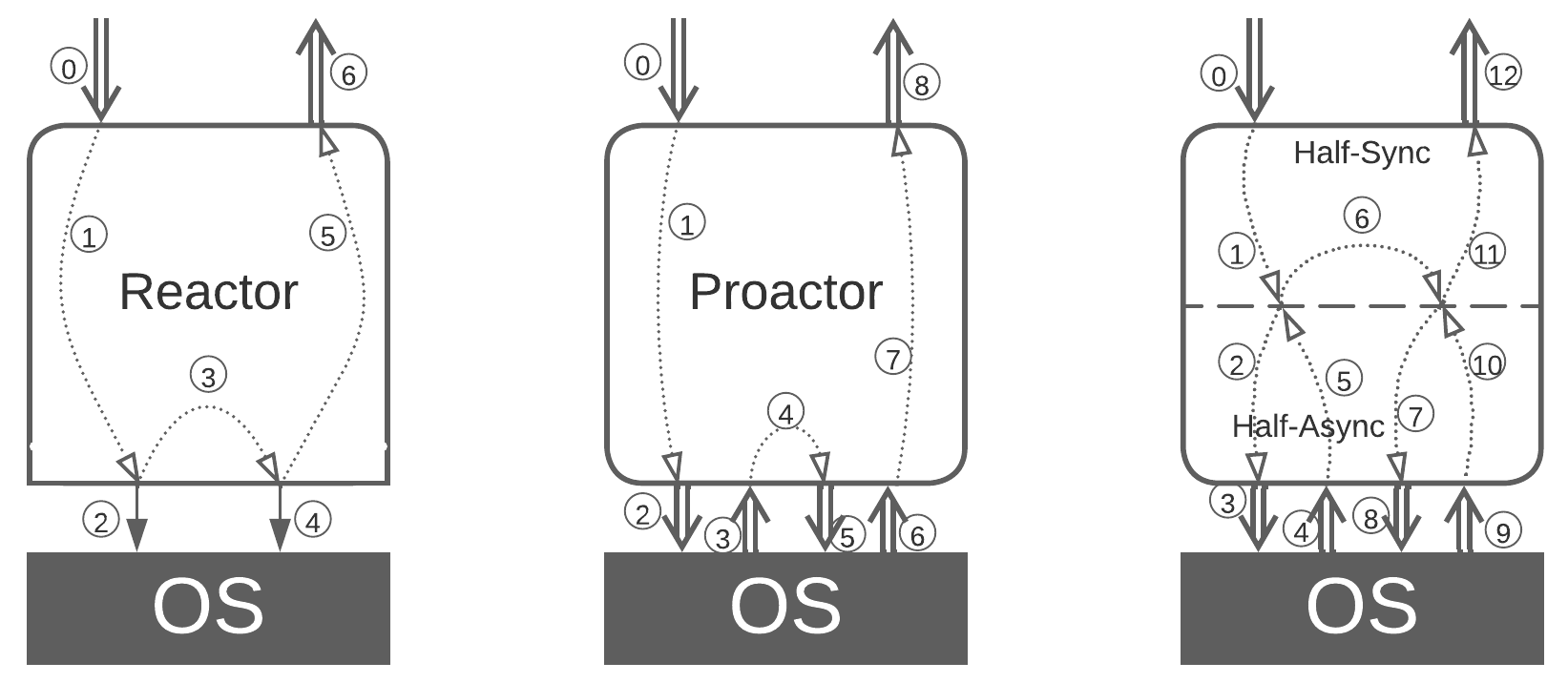

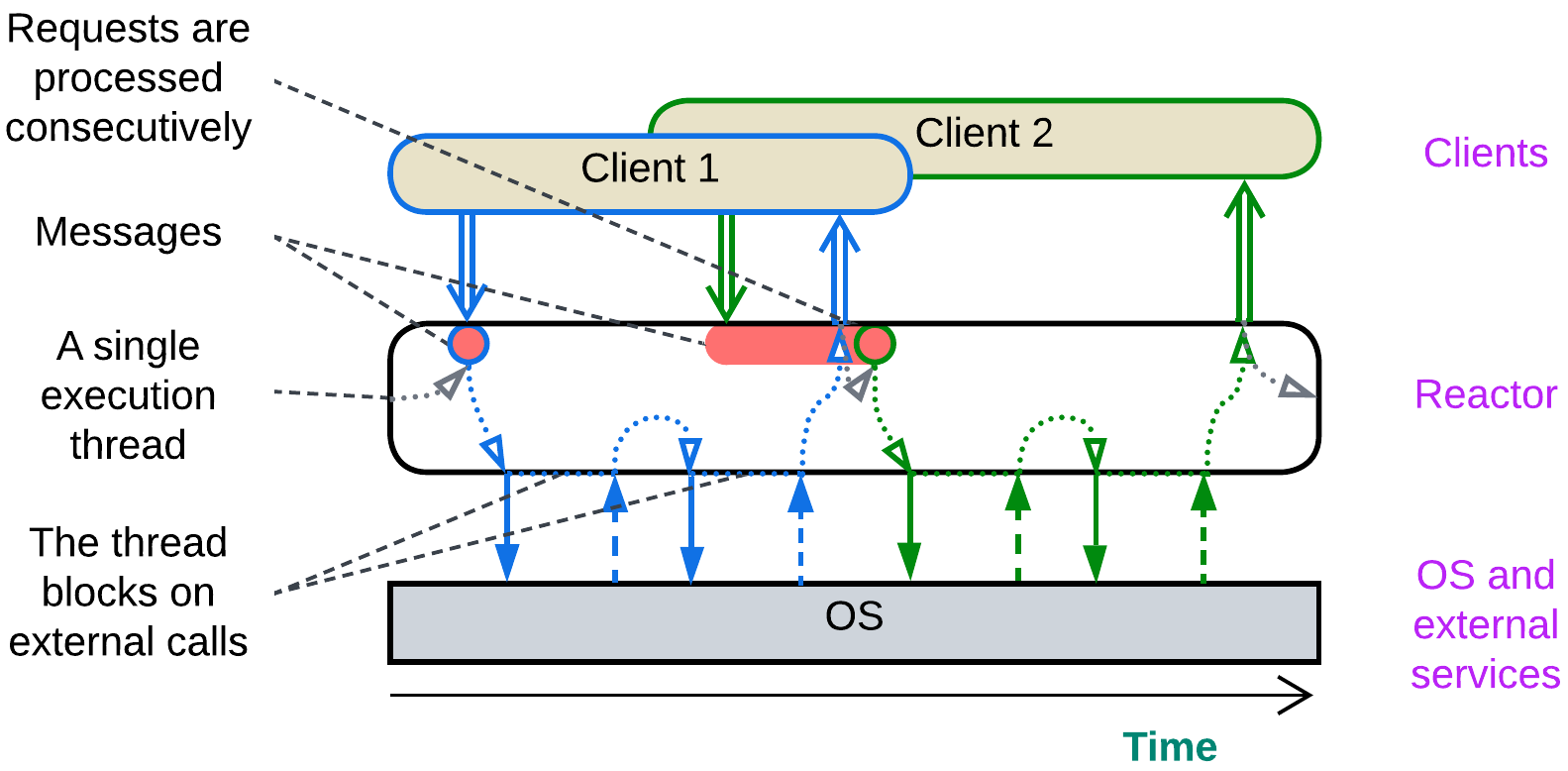

Single-threaded Reactor (one thread, one task) #

In a Reactor [POSA2] a single thread waits for an incoming event or data packet, processes it with blocking calls to the underlying OS, hardware, and external dependencies and returns the result, rinse and repeat.

That makes sense when the module owns and provides access to a hardware component which cannot do several actions at once, for example, a communication bus or a HDD firmware capable of a single read or write at any given moment.

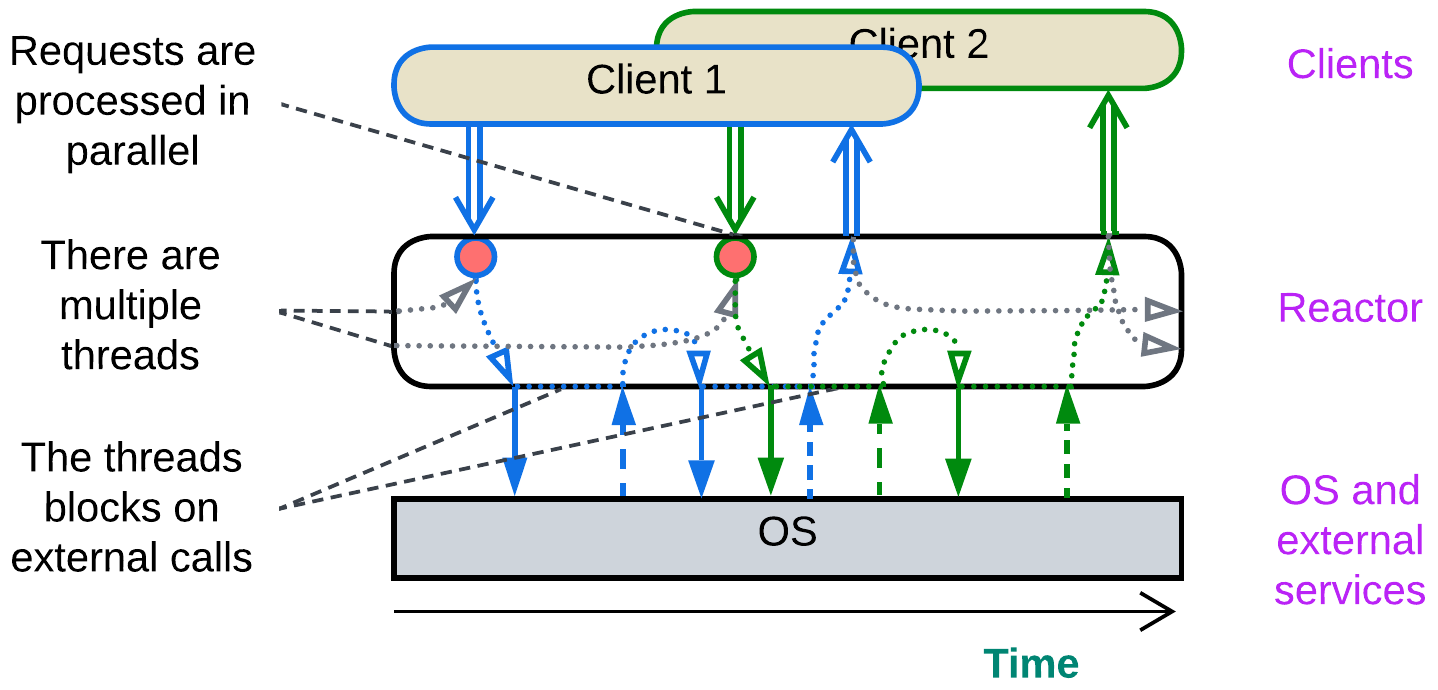

Multi-threaded Reactor (a thread per task) #

A Reactor [POSA2] may employ multiple threads by having a pool of them waiting for a request or data to come. The incoming event activates a thread, which becomes dedicated to processing it, does several blocking calls and, finally, sends back a response. When the request processing is complete, the thread returns to the pool of idle threads to wait for the next event to process.

This is the default simple & stupid implementation of backend services. Its pitfalls include contention for shared resources, deadlocks, and high memory consumption by OS-level threads.

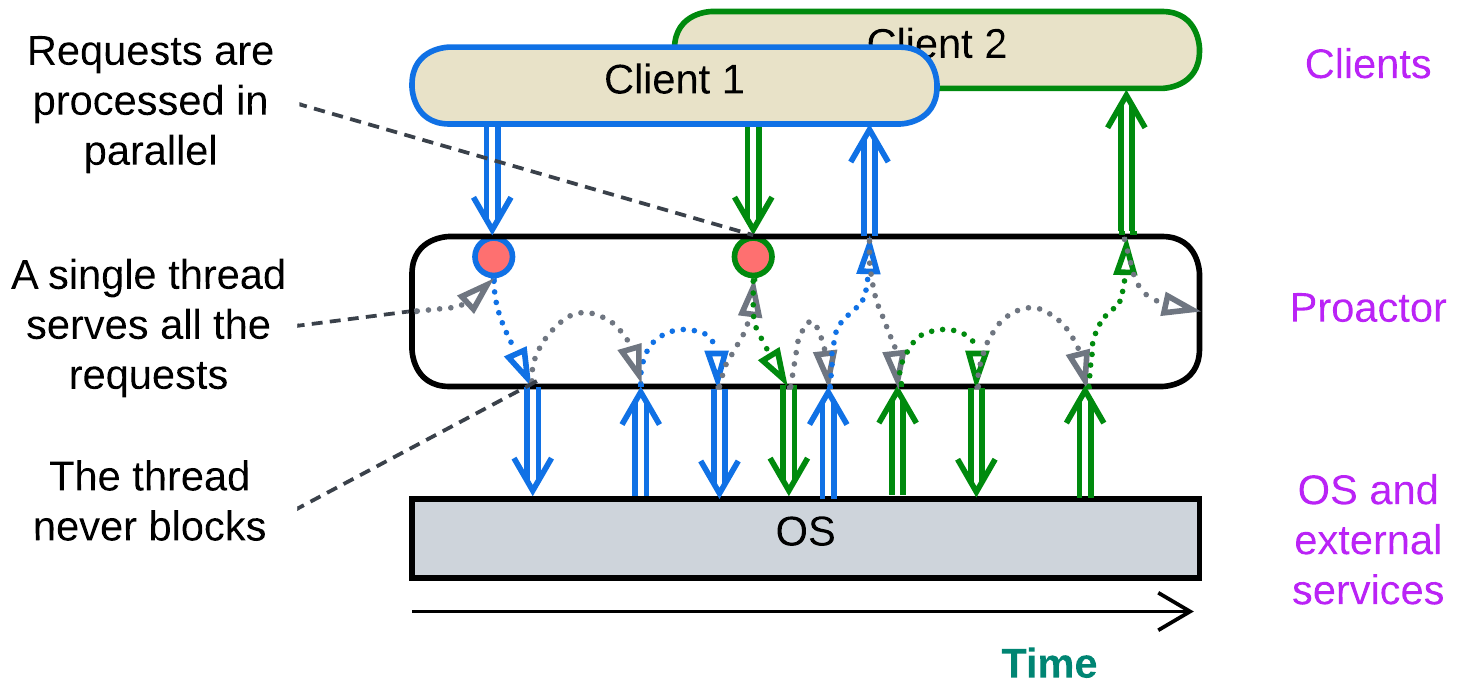

Proactor (one thread, many tasks) #

In Proactor [POSA2] a single thread processes all of the incoming events, both from the module’s clients and from the hardware or dependencies it manages. When an event is received, the thread goes through a short piece of corresponding business logic (event handler) which usually does one or more non-blocking actions, such as sending messages to other components, writing to registers of the managed hardware, or initiating an async I/O. As soon as the event handler returns, the thread becomes ready to process further events. As the thread never blocks, it is resource-efficient and serves many interleaved tasks.

This approach is good for real-time systems where thread synchronization is largely forbidden because of the associated delays and for reactive control applications which mostly adapt to the environment instead of running pre-programmed scenarios. The drawback is very poor structure of the code and debuggability as any complex behavior is broken into many independent event handlers.

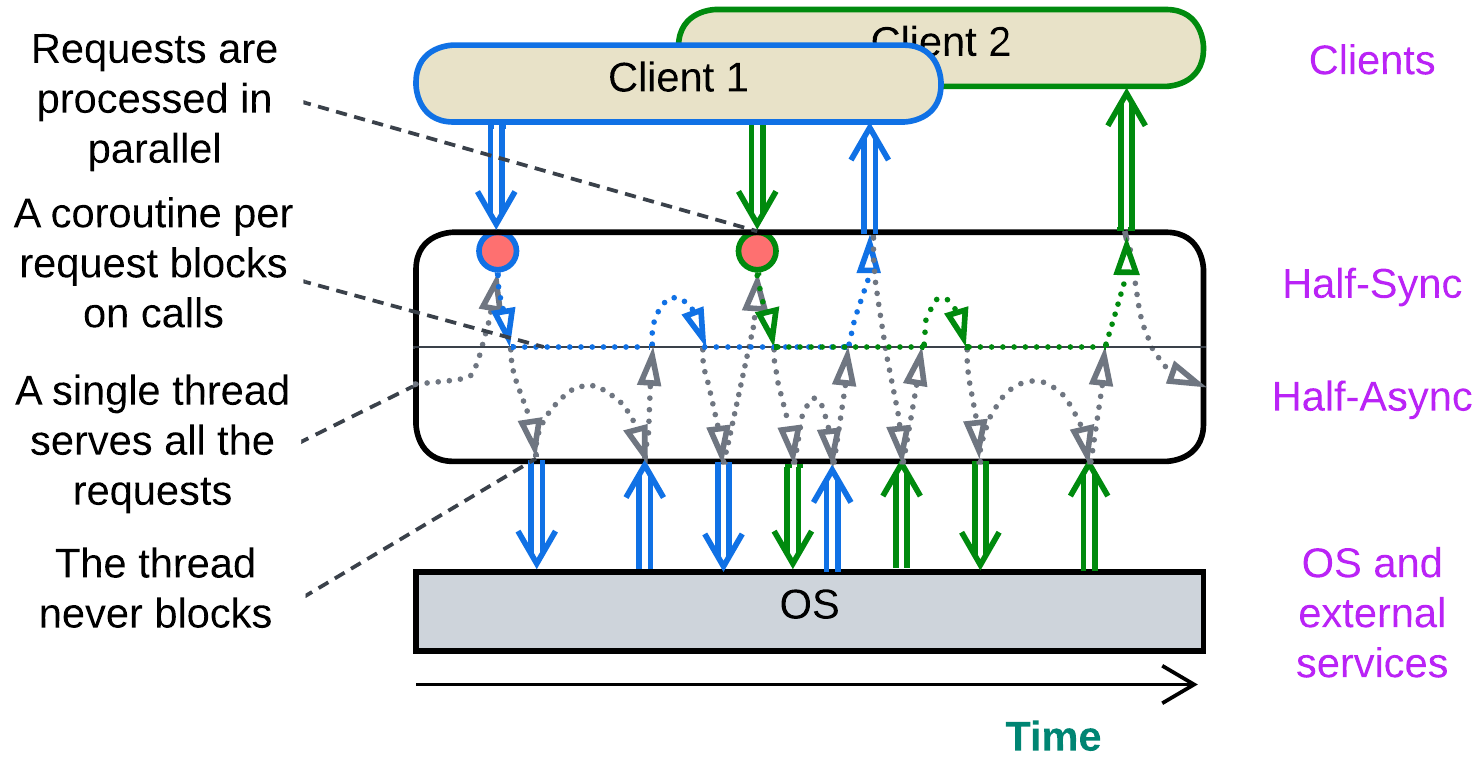

(inexact) Half-Sync/Half-Async (coroutines or fibers) #

Half-Sync/Half-Async [POSA2] originally described the interaction between user space and kernel threads in operating systems which is not much different from that behind coroutines and fibers. A single thread (or a thread pool with one thread per CPU core) handles all the incoming events and switches its call stack in the process.

Every incoming request is allocated a call stack which stores the processing state (local variables and methods called) of the request. When it needs to access an external component, the runtime system saves the request’s stack, does a non-blocking call, and the execution thread returns to its original stack to wait for any new event to handle while the request processing stack remains frozen until the action it has initiated completes asynchronously. Then the runtime switches the execution thread back to the stored request’s stack and continues processing the request until it completes and its stack is deleted.

This makes programming and debugging feel as easy as they are with Reactor (imperative style) while retaining the low resource consumption and high performance of Proactor (reactive paradigm). Coroutines and fibers are used in highly efficient game engines and databases. Though Half-Sync/Half-Async has two layers (is not truly monolithic), I believe it belongs next to Reactor and Proactor which make up its upper and lower halves, correspondingly.

The state of the art #

These patterns are not widely known and programmers tend to mix them together, for better or for worse. One is likely to encounter a heavily multithreaded big ball of mud where some threads serve user requests while others are dedicated to periodic service routines.

Moreover, people often call any event-driven service Reactor, causing confusion among those who distinguish between the three patterns.

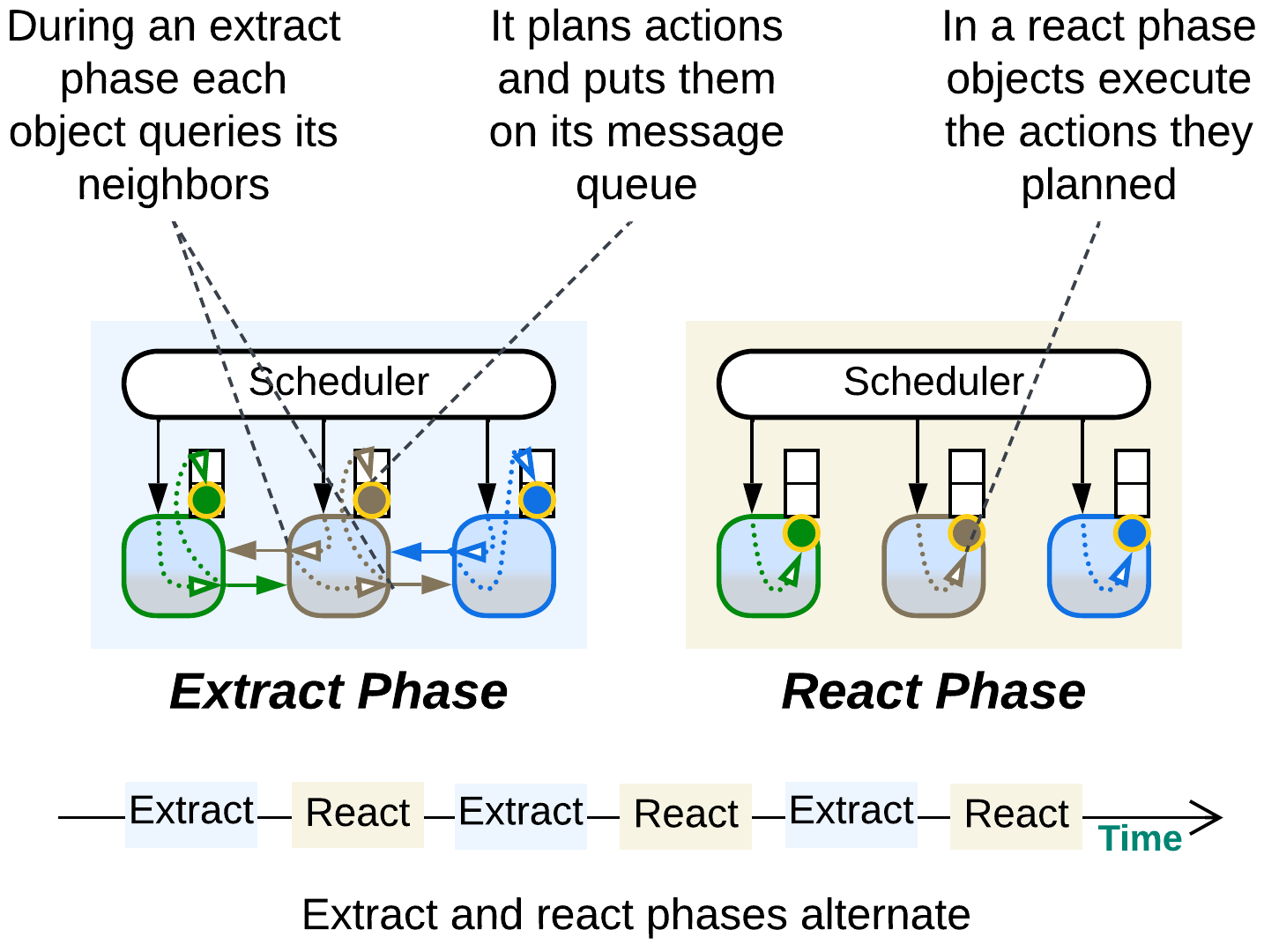

(inexact) (Re)Actor-with-Extractors (phased processing) #

As a bonus, let’s review an unconventional execution model that fits game development or other kinds of simulation with many interacting objects.

We have a long-running system where each simulated object with a complex behavior depends on the objects around it. Common wisdom proposes two ways to implement it:

- Actors (asynchronous messaging, reactive programming) – each actor (simulated object) runs single-threaded and wakes up only to process incoming messages. While processing a message, an actor may change its state and/or send messages to other actors. The entire actor’s data is private and there are no synchronous calls between the actors. The good thing is that actors are very efficient in highly parallel tasks as there are no locks in their code. The bad thing is that actors have no way to synchronize their states: you can only request another actor to tell you about its state, and its response may become outdated even before you receive it. Also, any complex logic that involves multiple actors is fragmented into many event handlers.

- The opposite approach is to have the simulated objects access each other synchronously. This allows for complex logic that depends on states of several objects but gets in trouble with changing the objects’ states from multiple threads: you need to protect them with those inefficient locks and you get those dreadful deadlocks as the outcome.

Here we see two bad options to choose from. However, it is the simulated nature of the system that saves the day: we can stop the world to get off. The objects’ querying each other and their changing their states neither needs to happen at the same time nor obey the same rules!

The simulation runs in steps. Each step consists of two phases:

- Query phase (extraction) is when the object states are immutable, thus the objects can communicate synchronously with no need for locks. In this phase each object collects information from its surroundings (other objects), plans its actions and posts them as commands to its own message queue. I suppose that objects may also send commands to each other in this phase.

- Command phase (reaction) is when each object executes its planned (queued) actions that change its state, but it cannot access other objects.

Each phase lasts until every object in the system completes its tasks scheduled for that particular phase. The phase toggle is supervised by a Scheduler which runs the objects on all the available CPU cores. The entire process resembles the game of Mafia with public daily conversations and covert nightly actions.

(Re)Actor-with-Extractors is the perfect example of earning the benefits of two architectures without paying the penalties. It utilizes both the lockless parallelism of Actors-style shared-nothing and the simplicity of synchronous access in shared-memory by alternating between those two modes through applying the CQRS principle to the time dimension.

Evolutions #

Every architecture has drawbacks and tends to evolve in a variety of ways to address them. Below is a brief summary of common evolutions of Monolith with more information available in Appendix E.

Evolutions to Shards #

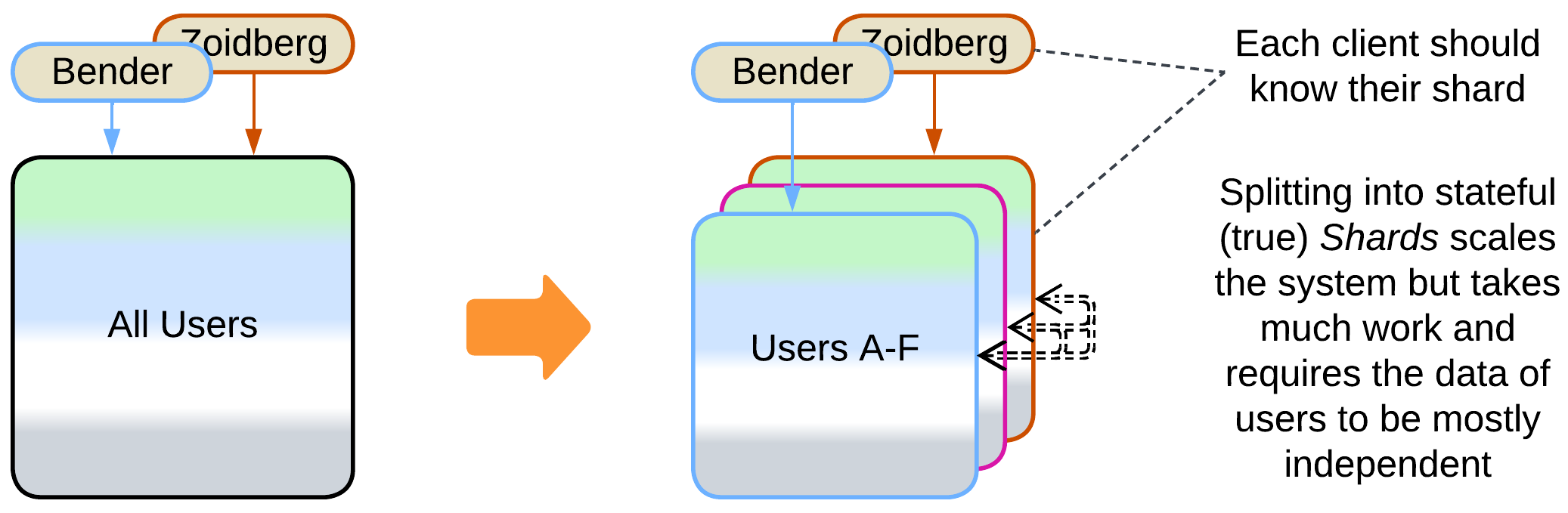

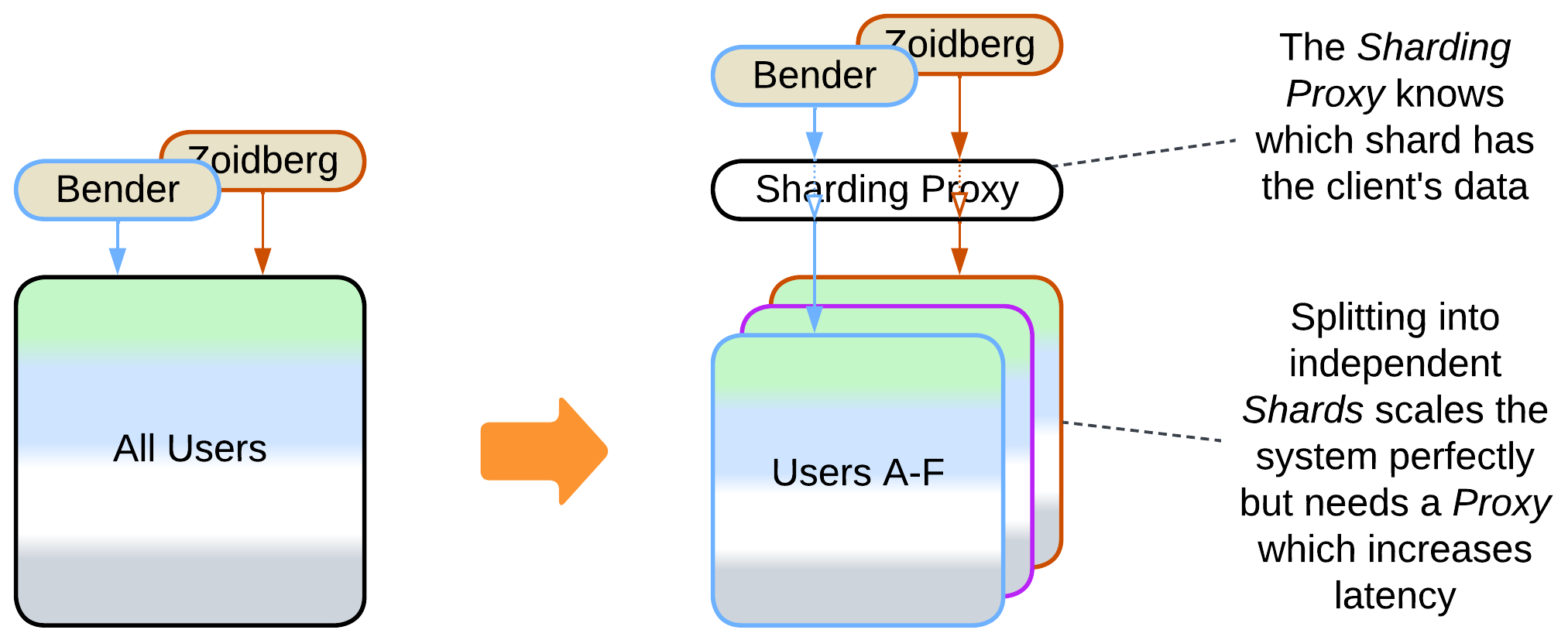

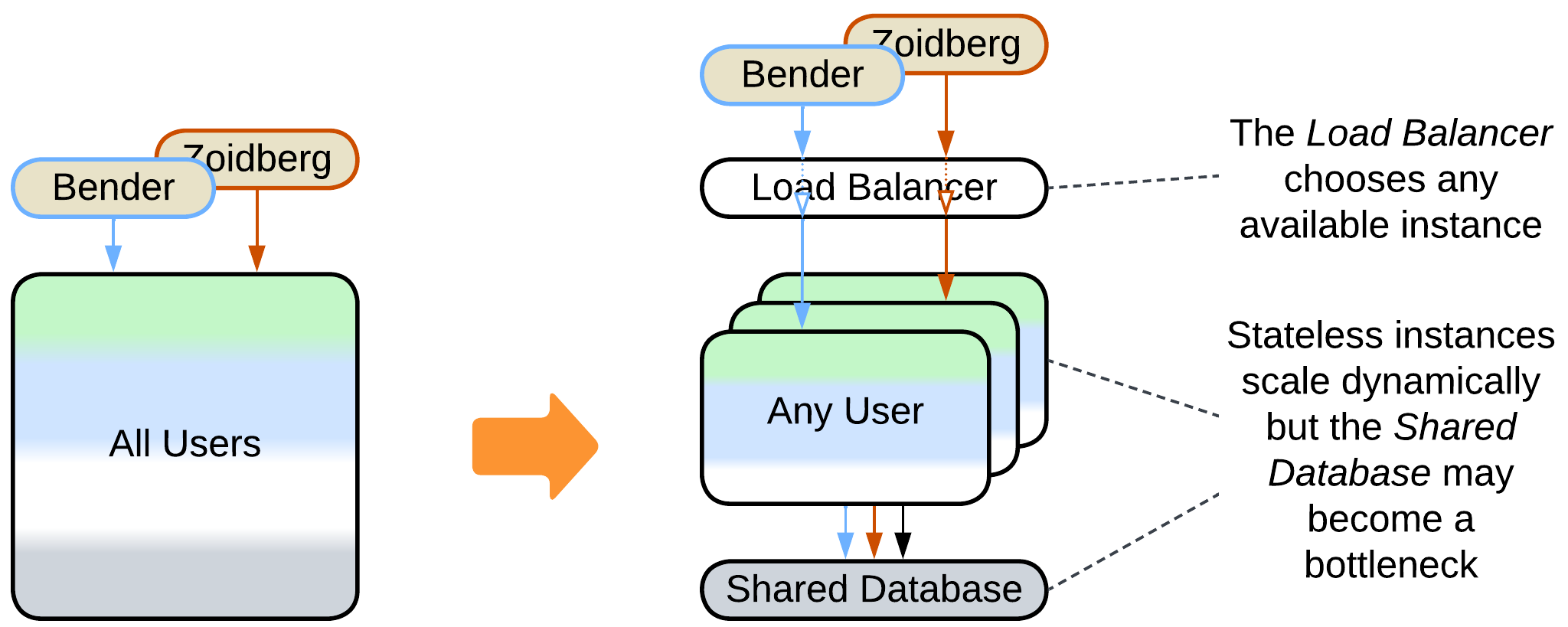

One of the main drawbacks of monolithic architecture is its lack of scalability – a single running instance of your system may not be enough to serve all the clients no matter how many resources you add in. If that is the case, you should consider Shards – multiple instances of a Monolith. There are following options:

- Self-managed Shards – each instance owns a part of the system’s data and may communicate with all the other instances (forming a Mesh).

- Shards with a Sharding Proxy – each instance owns a part of the system’s data and relies on an external component to choose a shard for a client.

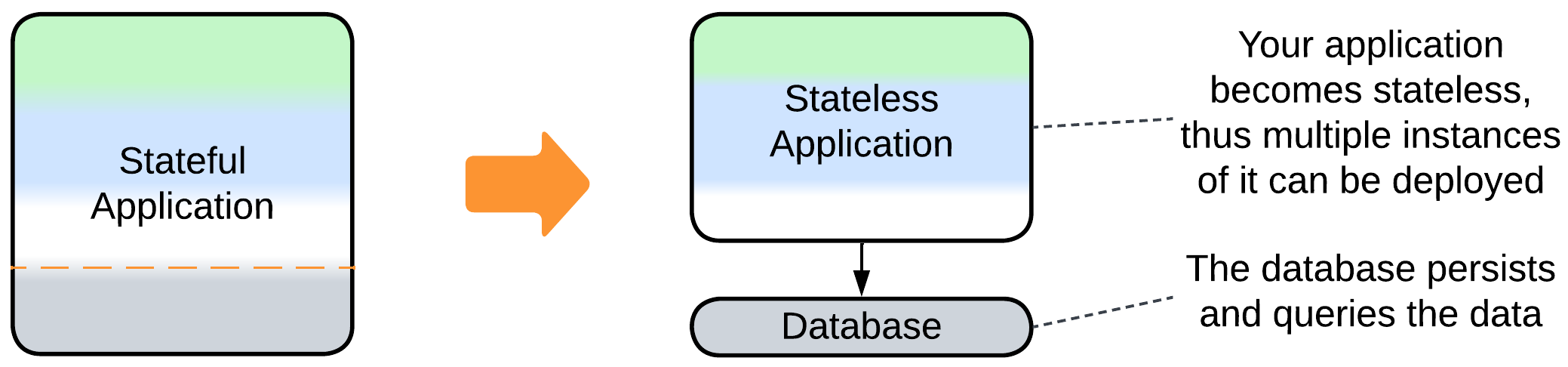

- A Pool of stateless instances with a Load Balancer and a Shared Database – any instance can process any request, but the database limits the throughput.

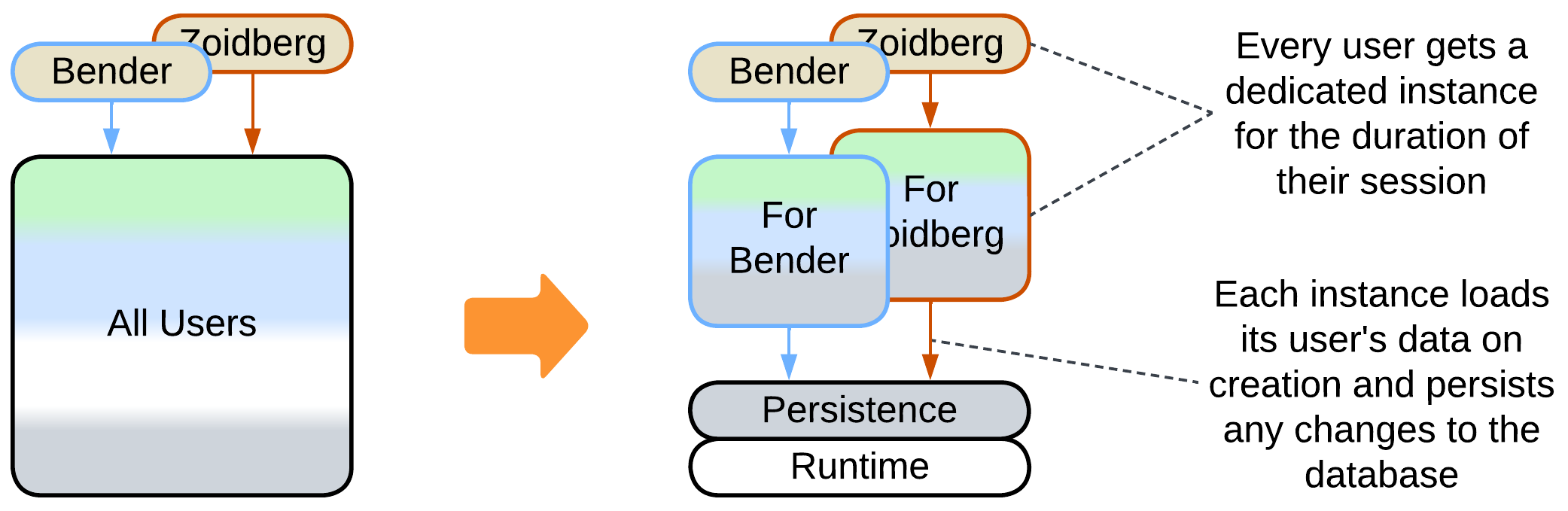

- A Stateful Instance per client with an external persistent storage – each instance owns the data related to its client and runs in a virtual environment (i.e. web browser or an Actor Framework).

Evolutions to Layers #

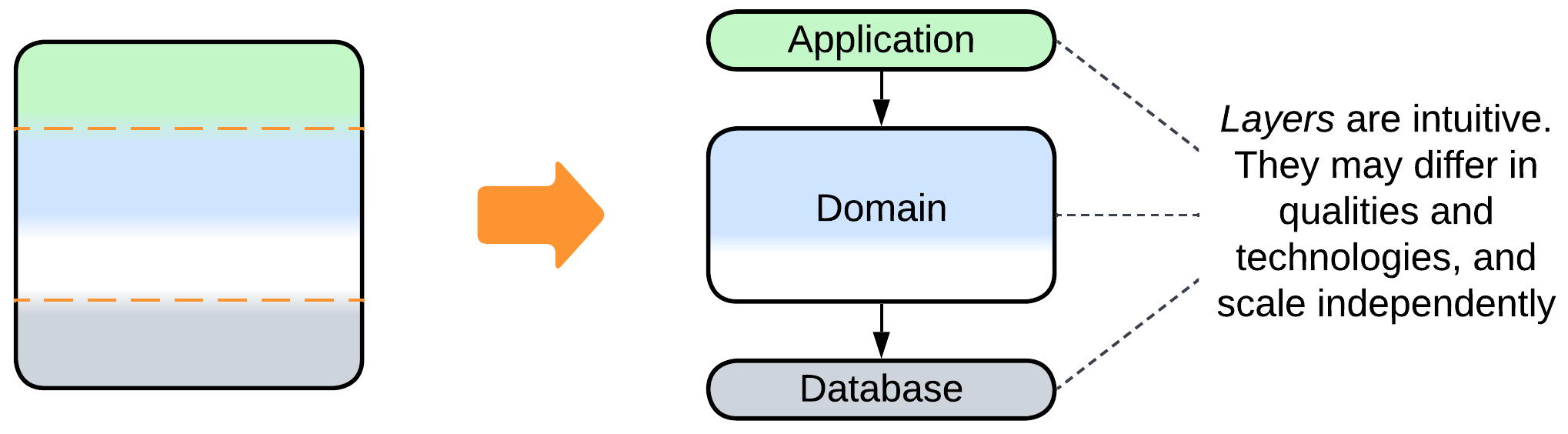

Another drawback of Monolith is its… er… monolithism. The entire application exposes a single set of qualities and all its parts (if they ever emerge) are deployed together. However, life awards flexibility: parts of a system may benefit from being written in varying languages and styles, deployed with different frequency and amount of testing, sometimes to specific hardware or end users’ devices. They may need to vary in security and scalability as well. Enter Layers – a subdivision by the level of abstractness:

- Most Monoliths can be divided into 3 or 4 layers of different abstractness.

- It is common to see the database separated from the main application.

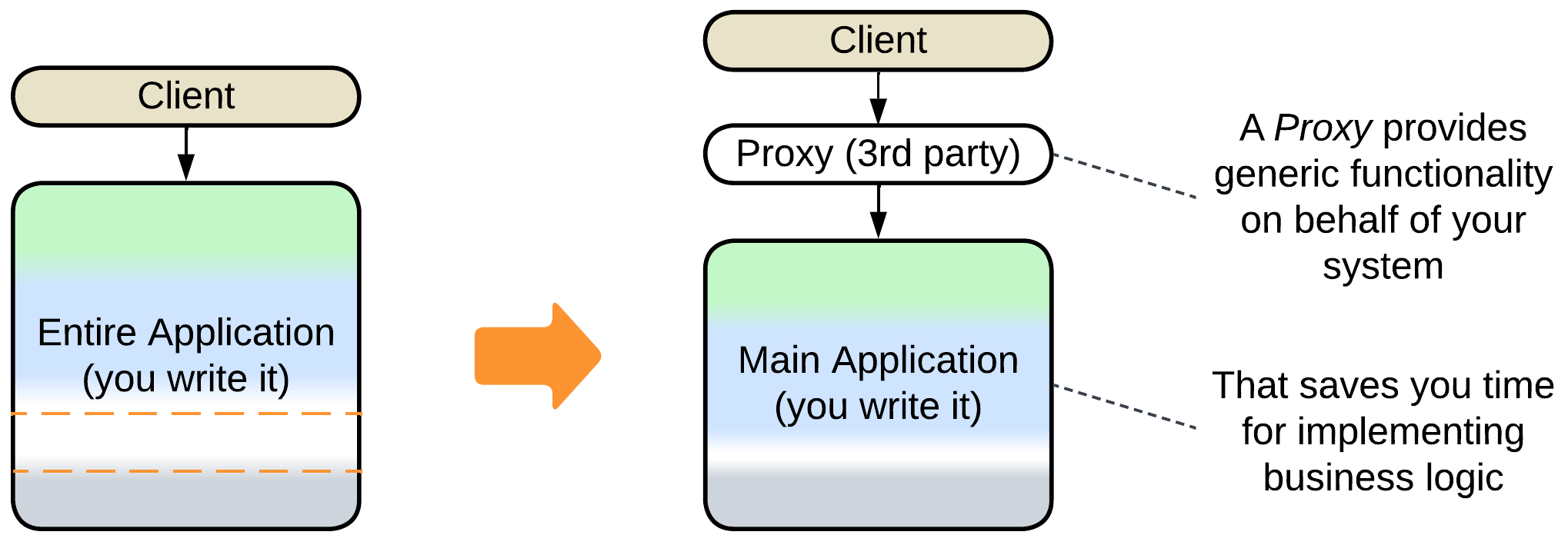

- Proxies (e.g. Firewall, Cache, Reverse Proxy) are common additions to the system.

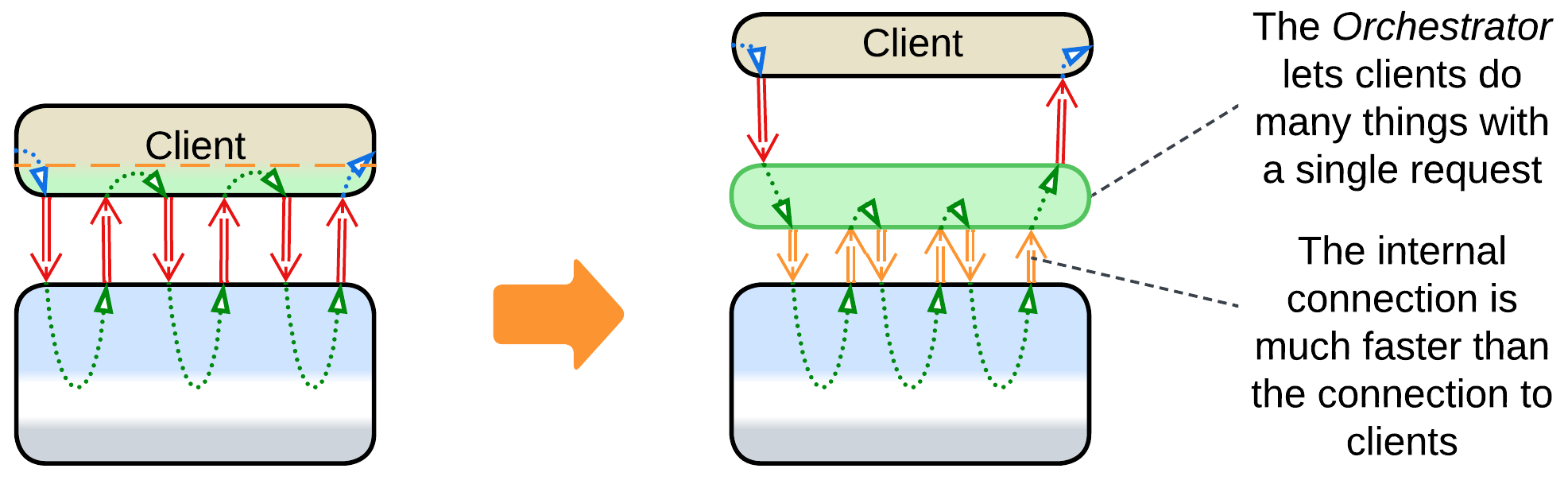

- An Orchestrator adds a layer of indirection to simplify the system’s external API.

Evolutions to Services #

The final major drawback of Monolith is the cohesiveness of its code. The rapid start of development with Monolith begets a major obstacle as the project grows: every developer needs to know the entire codebase to be productive while changes made by individual developers overlap and may break each other. Such distress is usually solved by dividing the project into modules along subdomain boundaries (which usually match bounded contexts). However, that requires much work, and good boundaries and APIs are hard to design. Thus many organizations prefer a slower iterative transition.

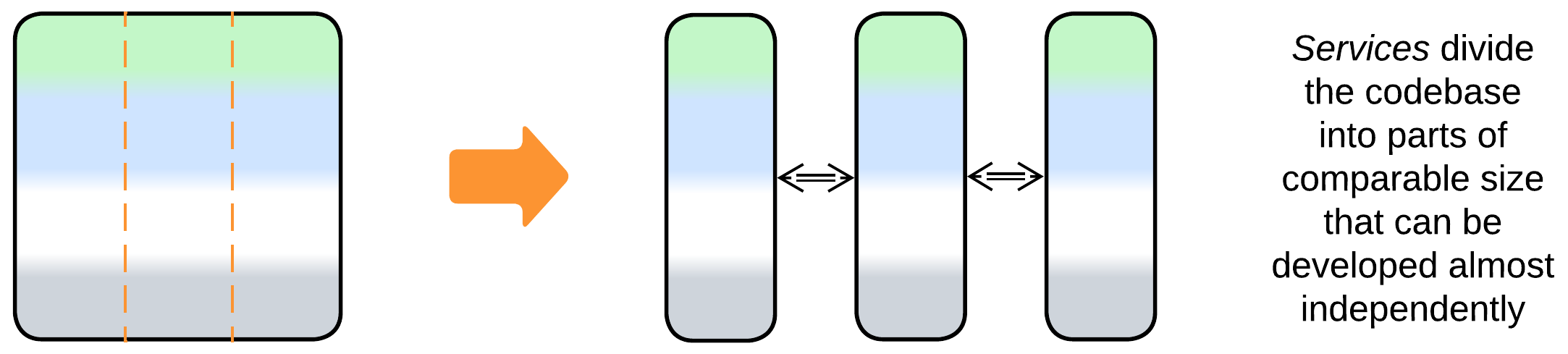

- A Monolith can be split into Services right away.

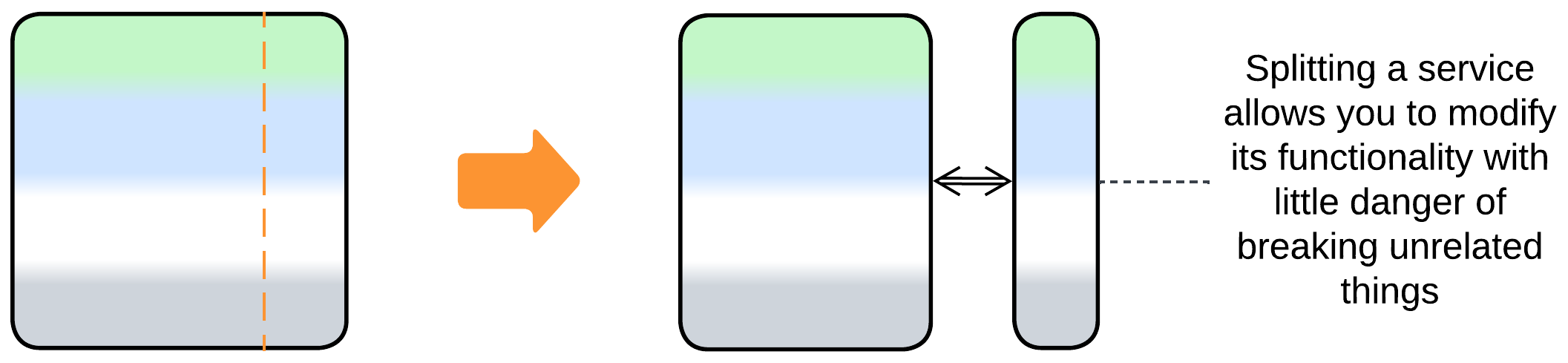

- A feature may be added or a weakly coupled part separated into a new service.

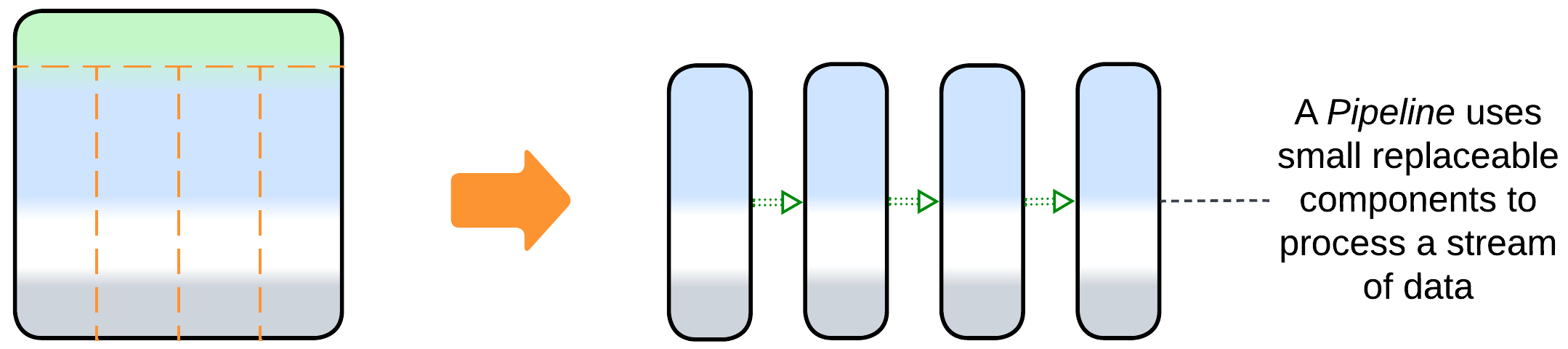

- Some domains allow for sequential data processing best described by Pipelines.

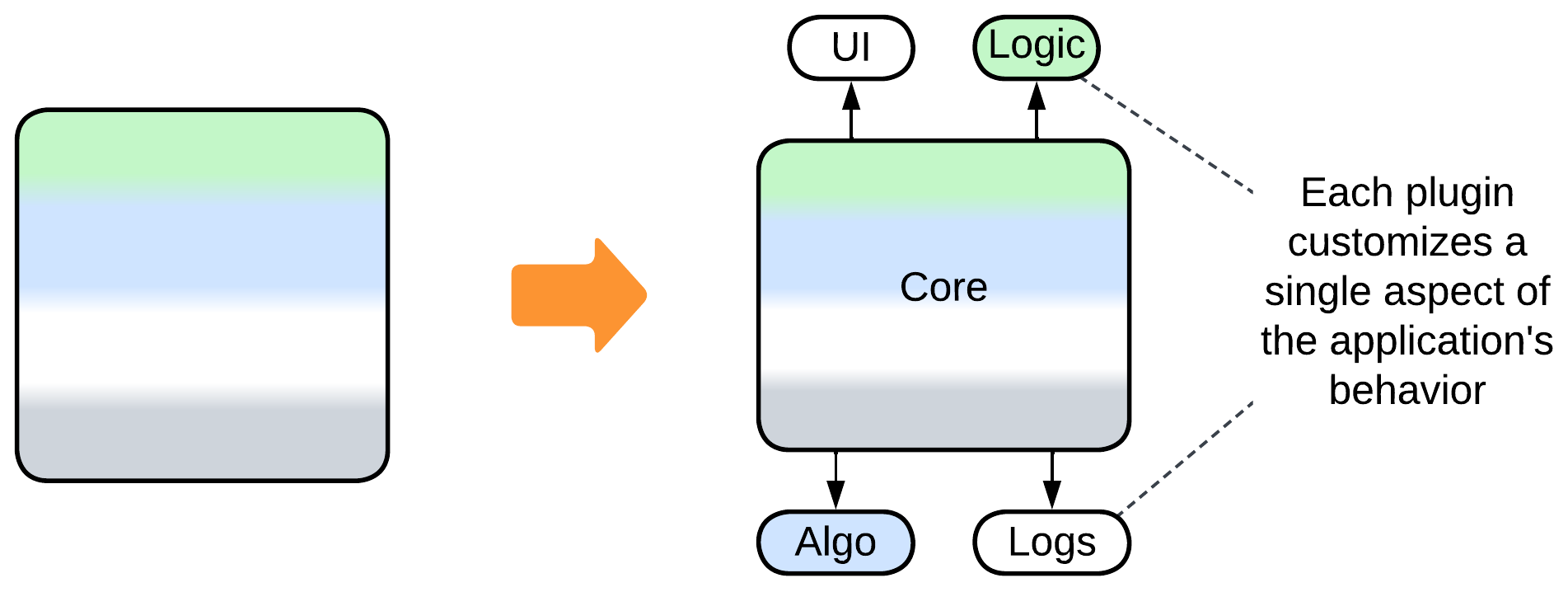

Evolutions with Plugins #

The last group of evolutions does not really change the monolithic nature of the application. Instead, its goal is to improve the customizability of the Monolith:

- Vanilla Plugins is the most direct approach which relies on replaceable bits of logic.

- Hexagonal Architecture is a subtype of Plugins which is all about isolating the main code from any third-party components it uses.

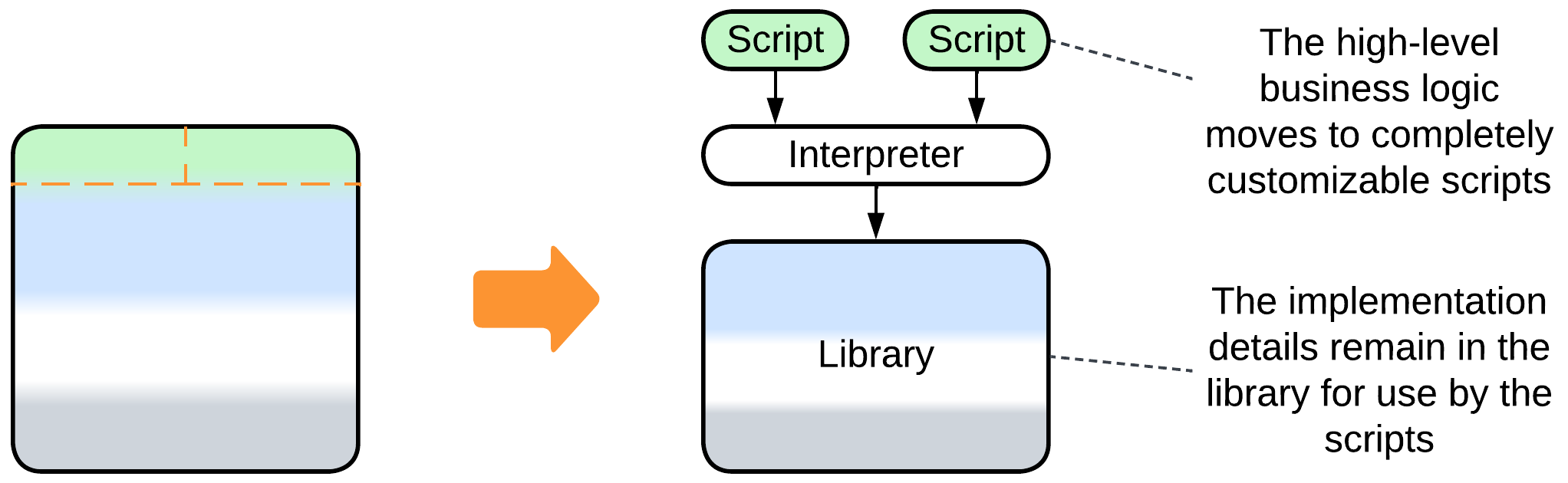

- Scripts is a kind of Microkernel – yet another subtype of Plugins – which gives users of the system full control over its behavior.

Summary #

A Monolith is an unstructured application. It is the best architecture for rapid prototyping by a small team and it usually grants the best performance to costs ratio. However, it does not scale, lacks any flexibility and becomes unmanageable as the amount of code grows.