Layers #

Yet another layer of indirection. Don’t mix the business logic and implementation details.

Known as: Layers [POSA1, POSA4], Layered Architecture [SAP, FSA, LDDD], Multitier Architecture, and N-tier Architecture [LDDD].

Variants: Open or closed, the number of layers.

By isolation:

- Synchronous layers / Layered Monolith [FSA],

- Asynchronous layers,

- A process per layer,

- Distributed tiers.

Examples:

- Domain-Driven Design (DDD) Layers [DDD],

- Three-Tier Architecture,

- Embedded Systems.

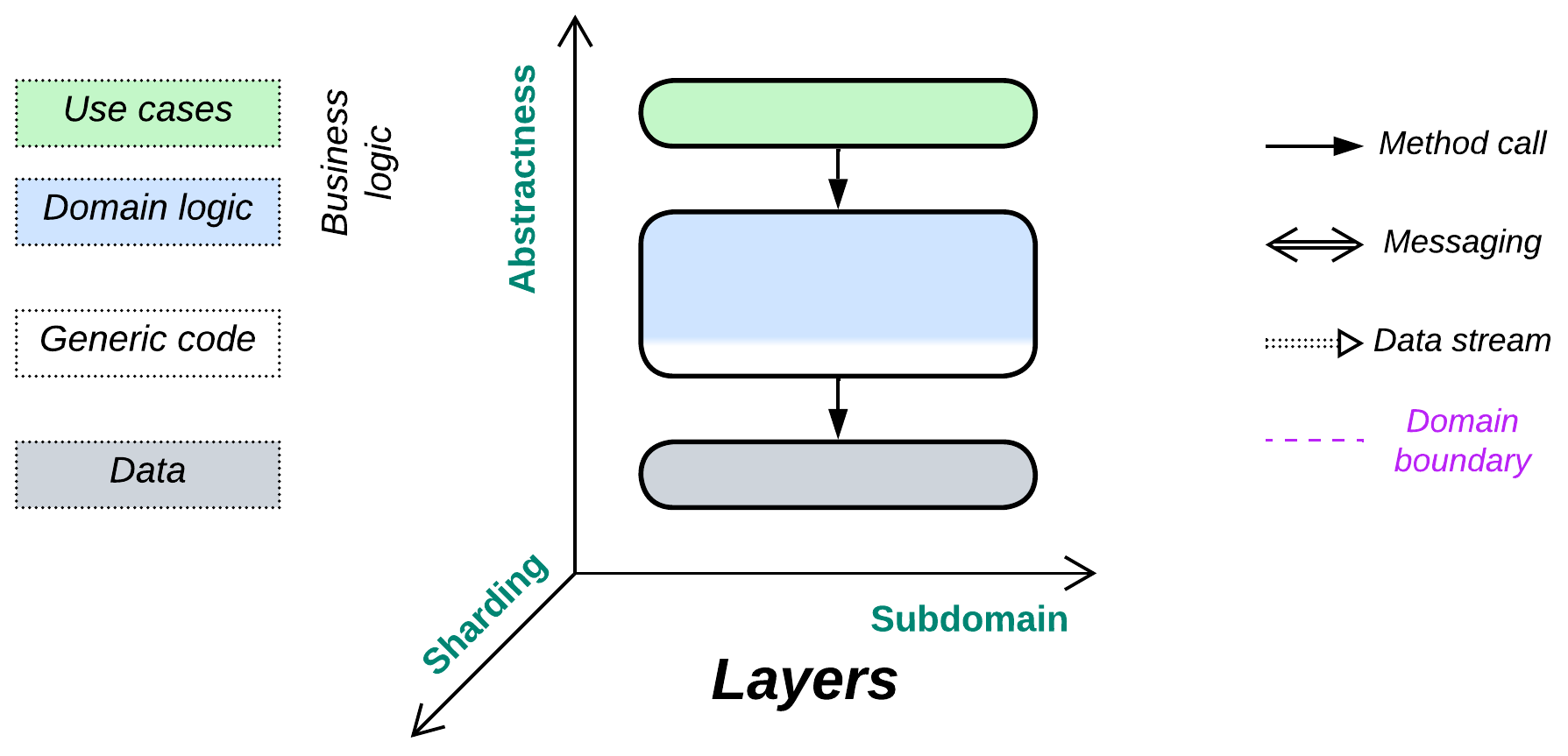

Structure: A component per level of abstractness.

Type: Main, implementation.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Rapid start for development | Quickly deteriorates as the project grows |

| Easy debugging | Hard to develop with more than a few teams |

| Good performance | Does not solve force conflicts between subdomains |

| Development teams may specialize | |

| Business logic is encapsulated | |

| Allows resolution of conflicting forces | |

| Deployment to dedicated hardware | |

| Layers with no business logic are reusable |

References: [POSA1] and [FSA] discuss layered software in depth; [DDD] promotes the layered style; most of the architectures in Herberto Graça’s Software Architecture Chronicles are layered. The Wiki has a reasonably good article.

Layering a system creates interfaces between its levels of abstractness (high-level use cases, lower-level domain logic, infrastructure) while also retaining monolithic cohesiveness within each of the levels. That allows both for easy debugging inside each individual layer (no need to jump into another programming language or re-attach the debugger to a remote server) and enough flexibility to have a dedicated development team, tools, deployment, and scaling policies for each. Though layered code is slightly better than that of Monolith, thanks to the separation of concerns, one of the upper (business logic) layers may nonetheless grow too large for efficient development.

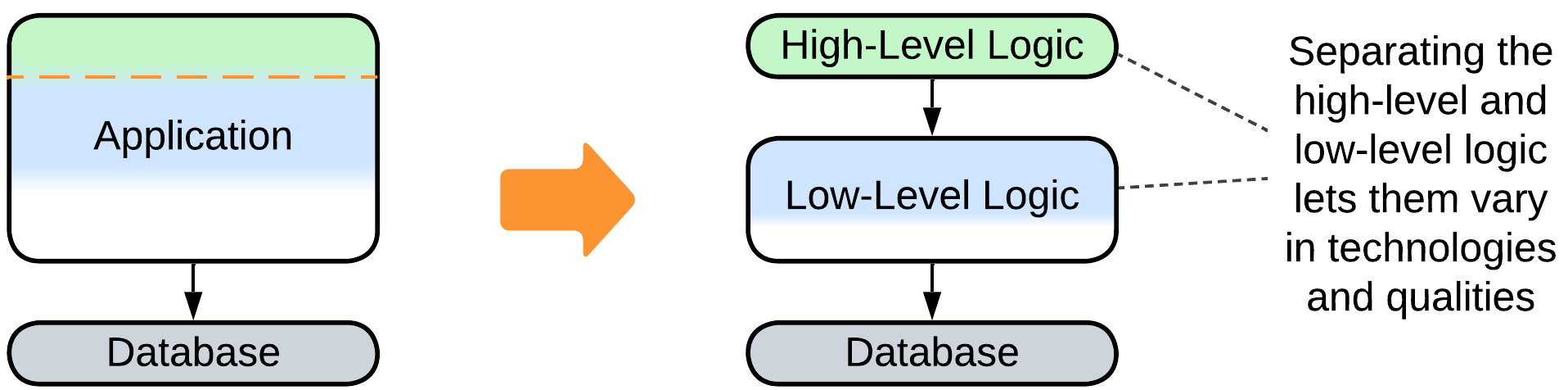

Splitting a system into layers tends to resolve conflicts of forces between its abstract and optimized parts: the top-level business logic changes rapidly and does not require much optimization (as its methods are called infrequently), thus it can be written in a high-level programming language. In contrast, infrastructure, which is called thousands of times per second, has stable workflows but must be thoroughly optimized and extremely well tested.

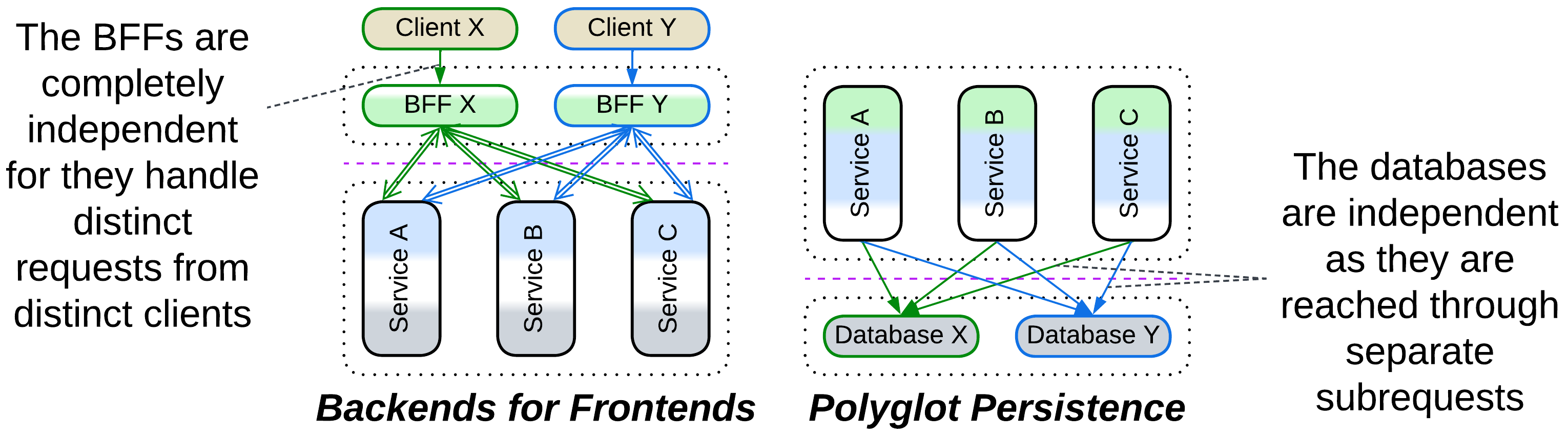

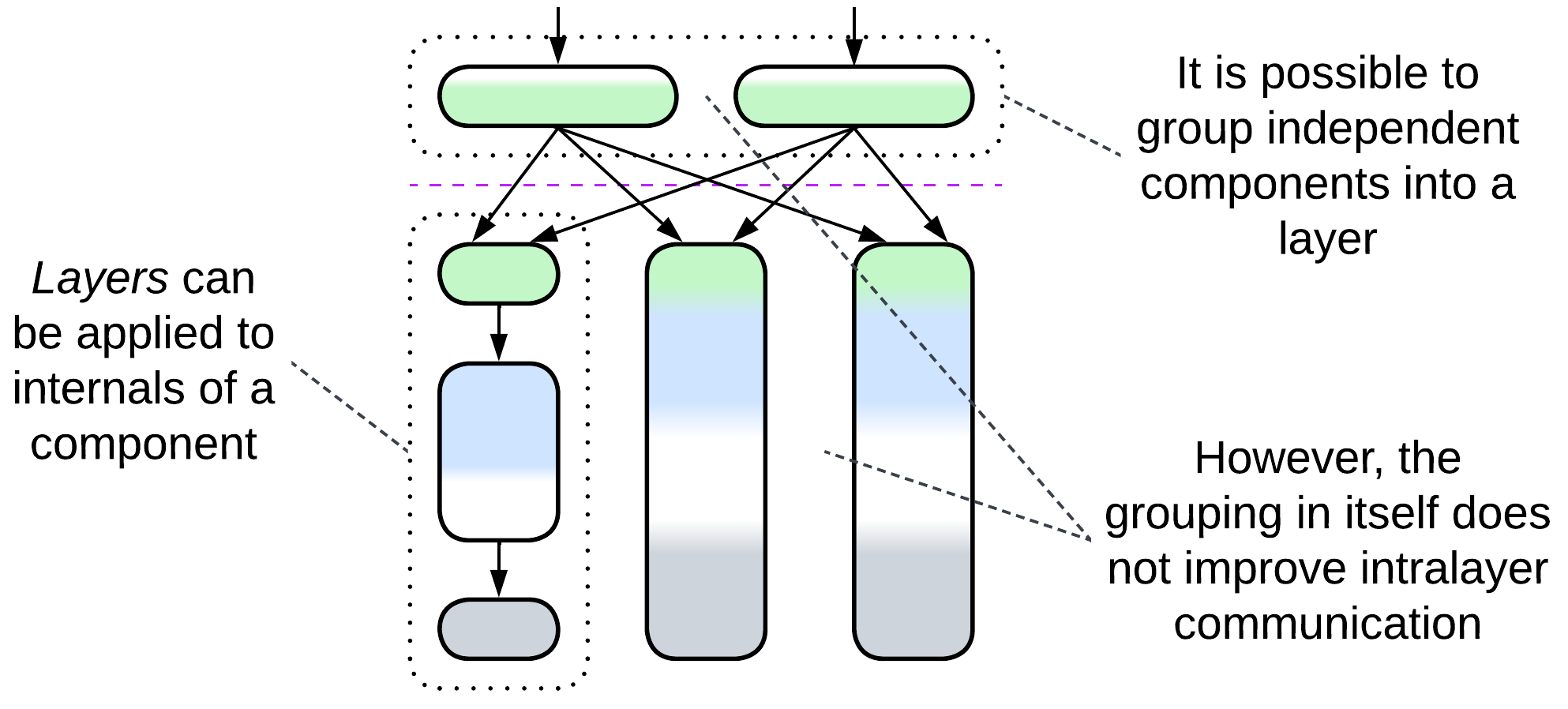

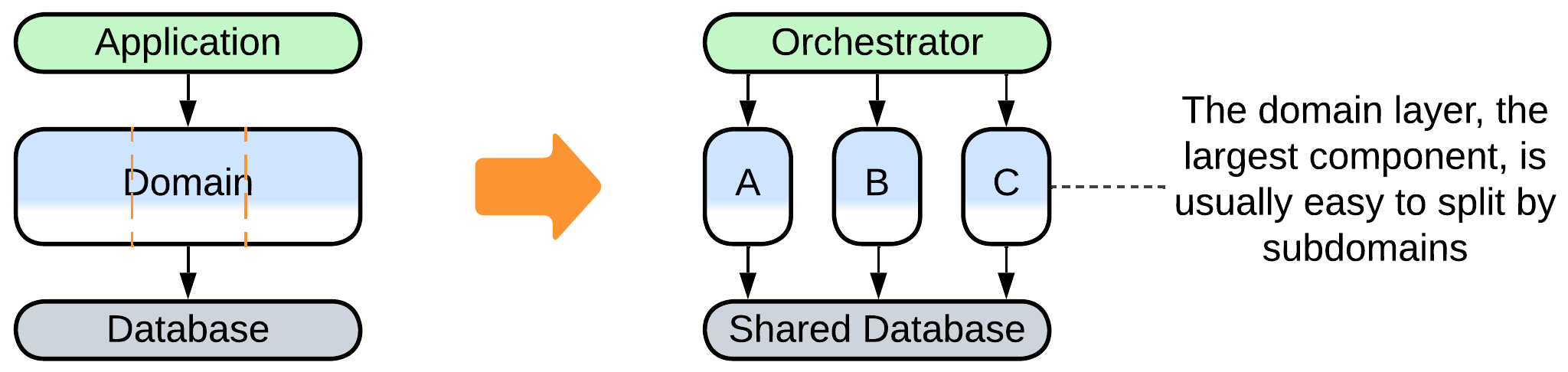

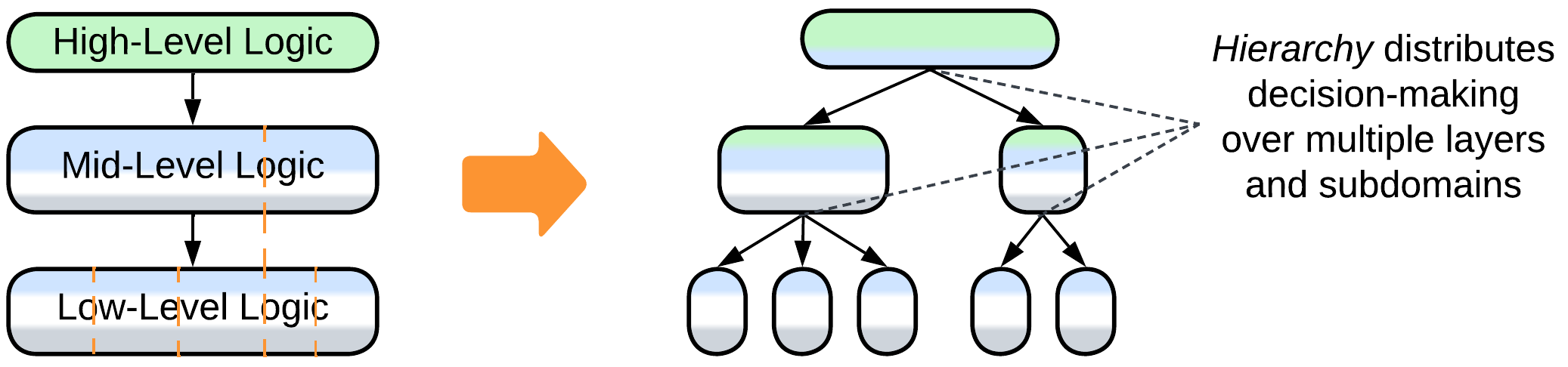

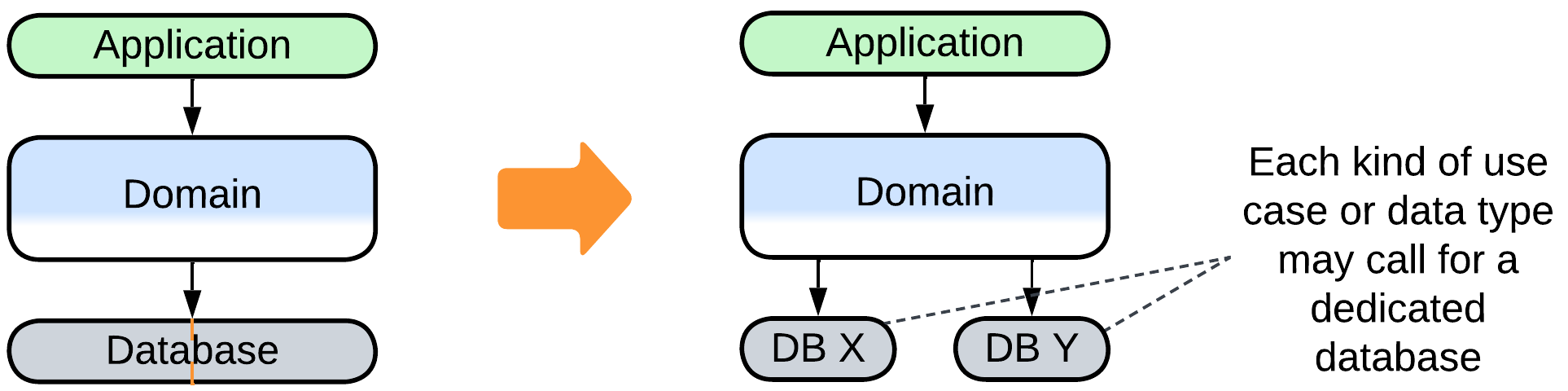

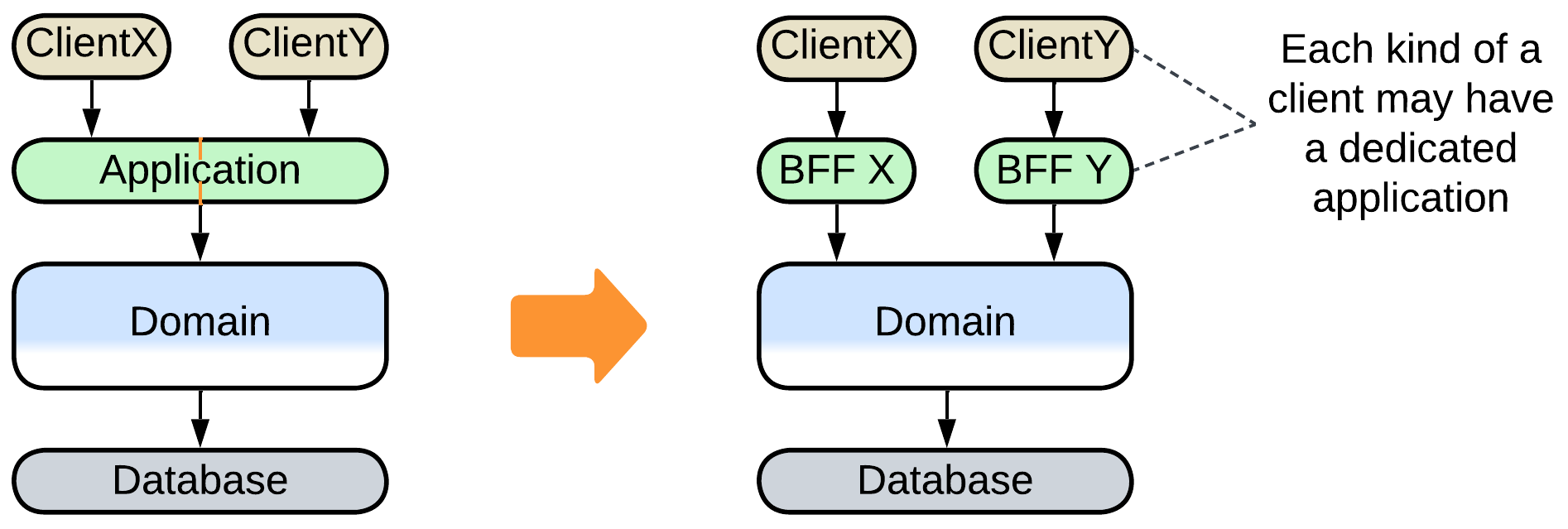

Many patterns have one or more of their layers split by subdomain, resulting in a layer of services. That causes no penalties as long as the services are completely independent (the original layer had zero coupling between its subdomains), which happens if each of them deals with a separate subset of requests (as in Backends for Frontends) or is choreographed by an upper layer (as in Polyglot Persistence, Hexagonal Architecture or Hierarchy) which boils down to the same “separate subset of subrequests” under the hood. However, if the services which form a layer need to intercommunicate, you immediately get a whole set of troubles with debugging, sharing data, and performance characteristic of the Services architecture.

Thanks to its substantial benefits and minor drawbacks, and the many evolutions it supports, Layers became the default architecture for starting new projects.

Performance #

The performance of a layered system is shaped by two factors:

- Communication between layers is slower than within a layer. Components of a layer may access each other’s data directly, while accessing another layer involves data transformation (as interfaces tend to operate generic data structures), serialization, and often IPC or networking.

- The frequency and granularity of events or actions increases as we move from the upper more abstract layers to lower-level components that interface an OS or hardware.

An ideal component should be replaceable and reusable. As soon as a component exposes details of its implementation, such as workflows or data types, in its interface, it becomes incompatible with other possible implementations, and its interface may even see major changes as the internals of the component evolve. Therefore, well-behaving components tend to have their interfaces written in most generic terms, which requires inputs to be transformed to their internal formats and thus penalizes performance.

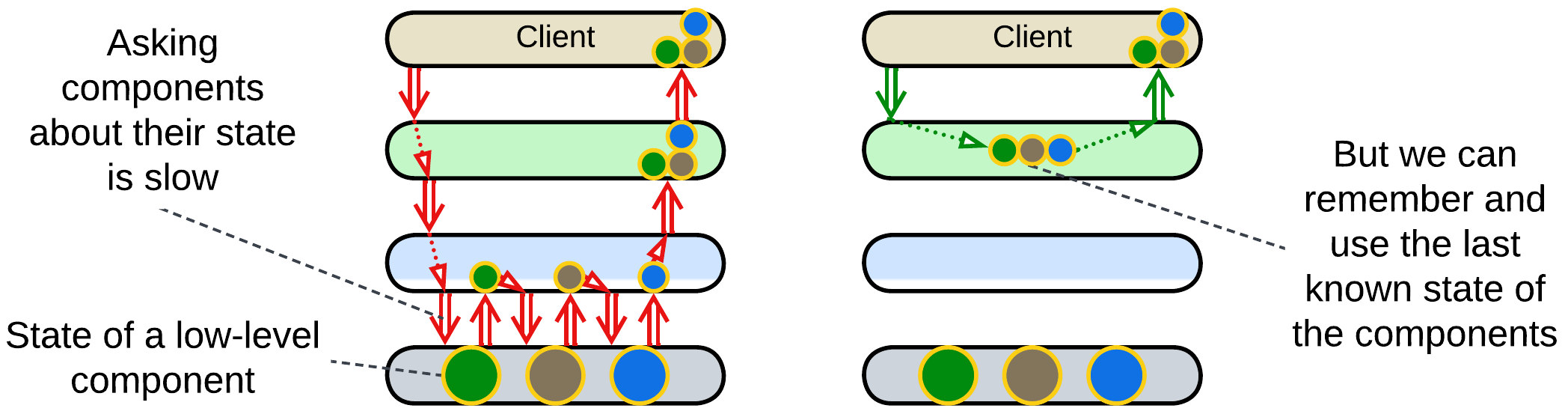

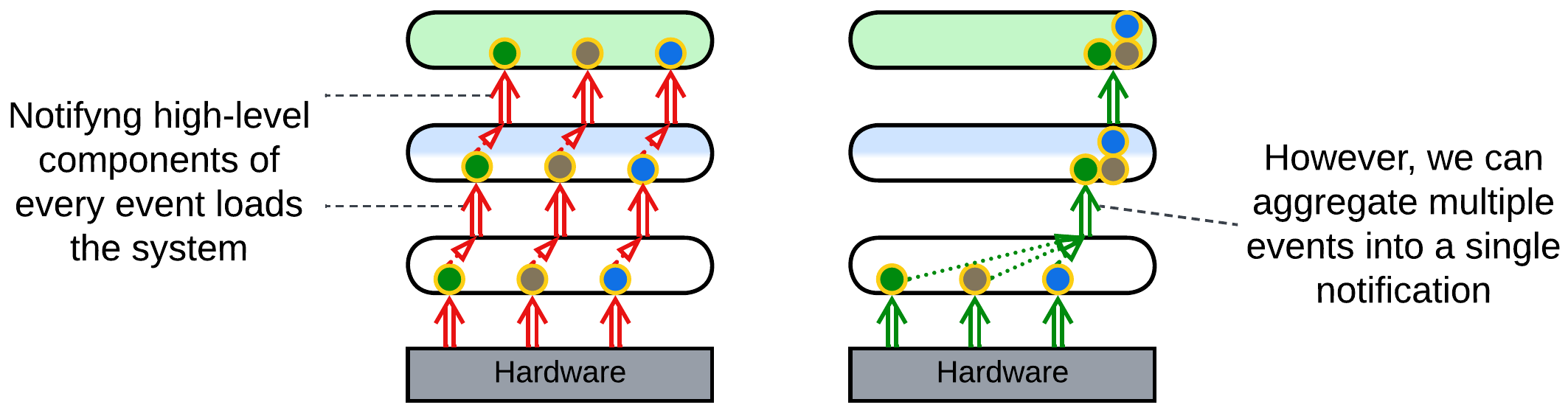

There is a number of optimizations to skip interlayer calls:

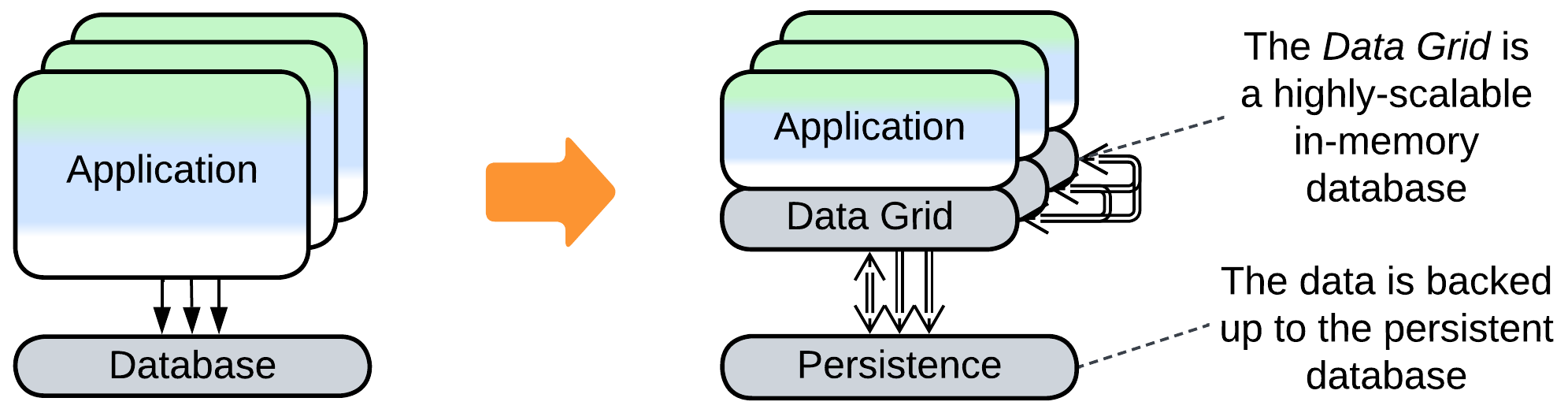

Caching: an upper layer tends to model (cache last known state of) the layers below it. This way it can behave as if it knew the state of the whole system without querying the actual state from the hardware below all the layers. Such an approach is universal for control software. For example, a network monitoring suite shows you the last known state of all the components it observes without actually querying them – it is subscribed to notifications and remembers what each device has previously reported.

Aggregation: a lower layer collects multiple events before notifying the layer above it to avoid being overly chatty. An example is an IIoT field gateway that collects data from all the sensors in the building and sends it in a single report to the server. Or consider a data transfer over a network where a low-level driver collects multiple data packets that come from the hardware and sends an acknowledgement for each of them while waiting for a datagram or file transfer to complete. It notifies its client only once when all the data has been collected and its integrity confirmed.

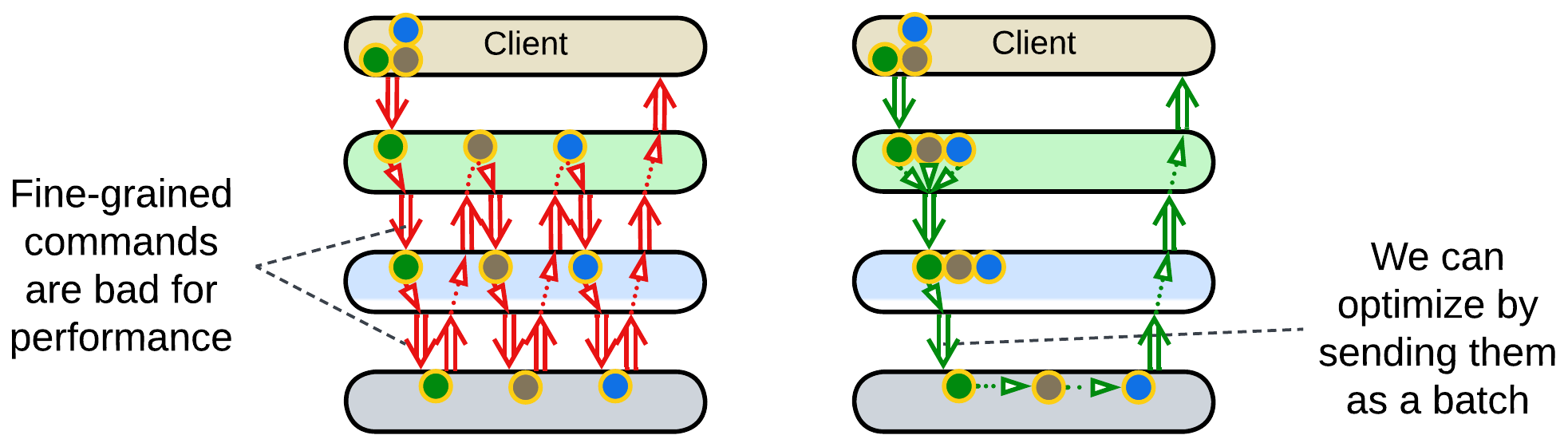

Batching: an upper layer forms a queue of commands and sends it as a single job to the layer below it. This takes place in drivers for complex low-level hardware, like printers, or in database access as stored procedures. [POSA4] describes the approach as Combined Method, Enumeration Method and Batch Method patterns. Programming languages and frameworks may implement foreach and map/reduce which allow for a single command to operate on multiple pieces of data.

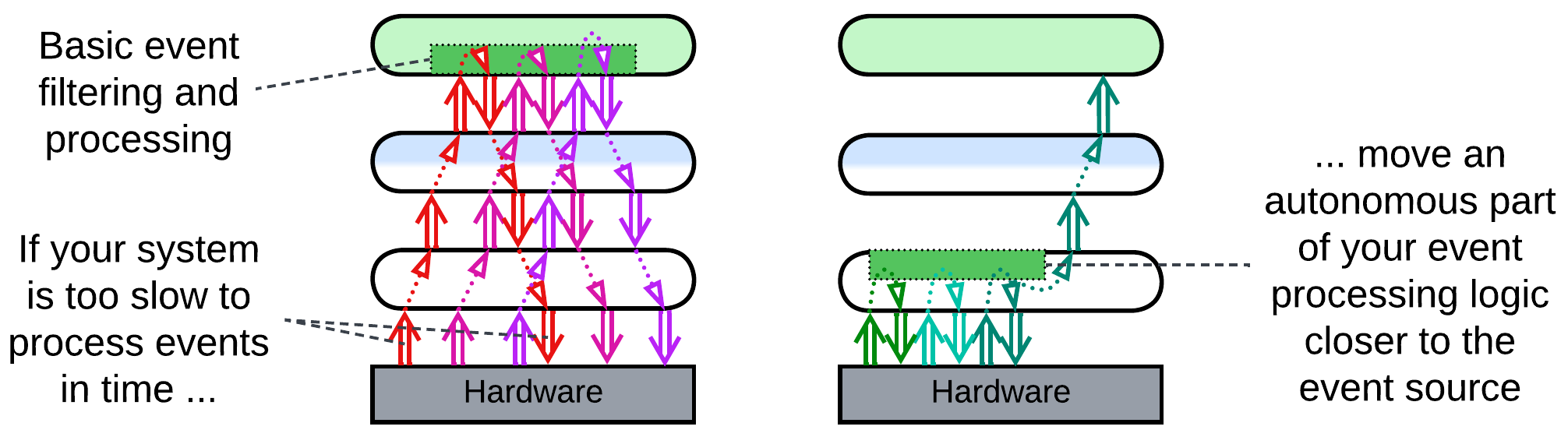

Strategy injection: an upper layer installs an event handler (hook) into the lower layer. The goal is for the hook to do basic pre-processing, filtering, aggregation, and decision making to process the majority of events autonomously while escalating to the upper layer in exceptional or important cases. That may help in such time-critical domains as high-frequency trading.

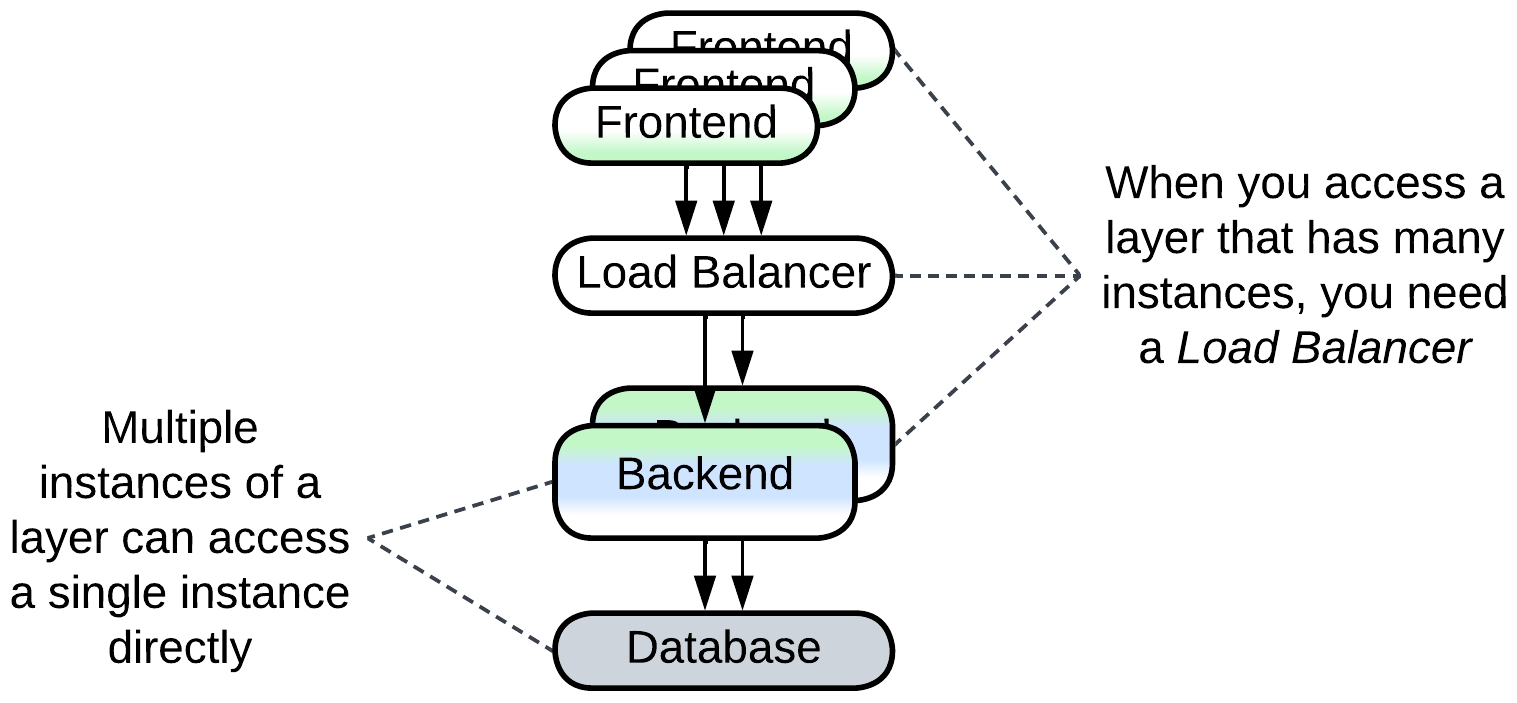

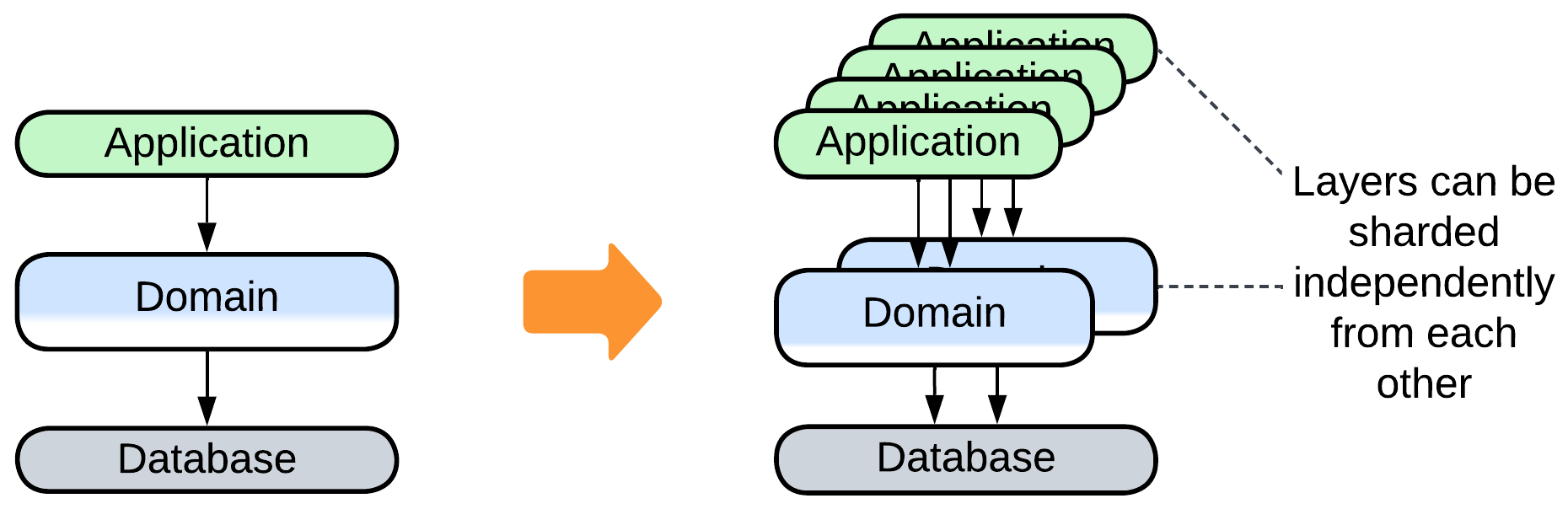

Layers can be scaled independently, as exemplified by common web applications that comprise a highly scalable and resource-consuming frontend, somewhat scalable backend and unscalable data layer. Another example is an OS (lower layer) that runs multiple user applications (upper layer).

Dependencies #

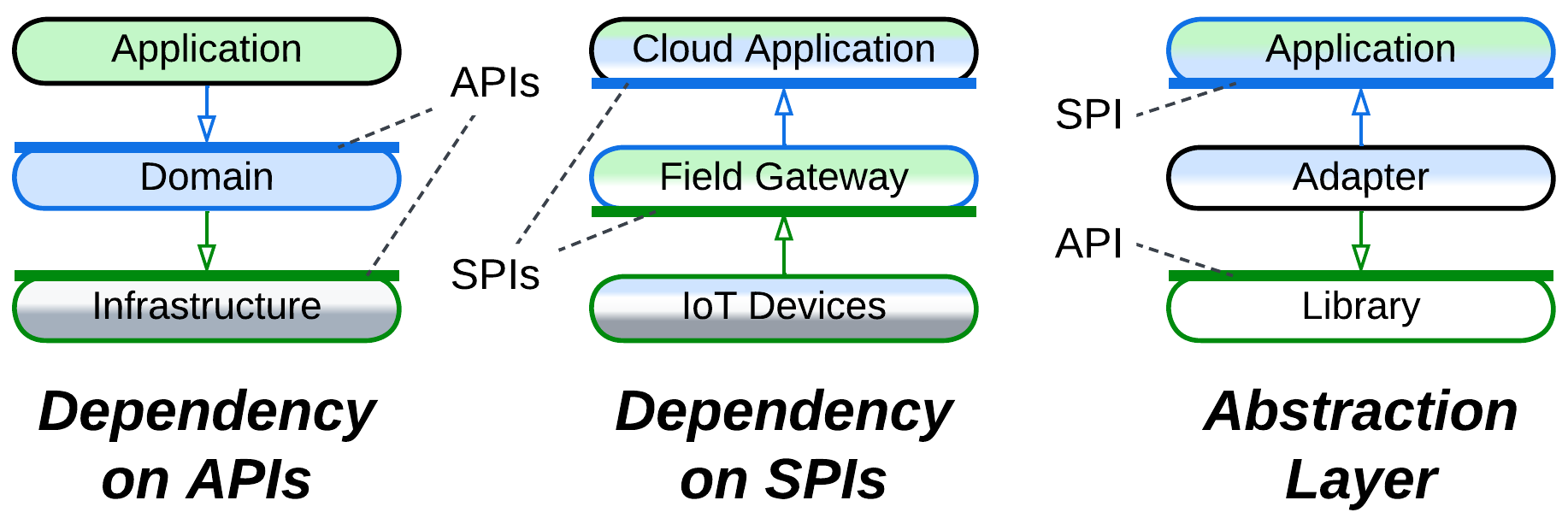

Usually an upper layer depends on the API (application programming interface) of the layer directly below it. That makes sense as the lower the layer is, the more stable it tends to be: a user-facing software gets updated on a daily or weekly basis while hardware drivers may not change for years. As every update of a component may destabilize other components that depend on it, it is much more preferable for a quickly evolving component to depend on others instead of the other way round.

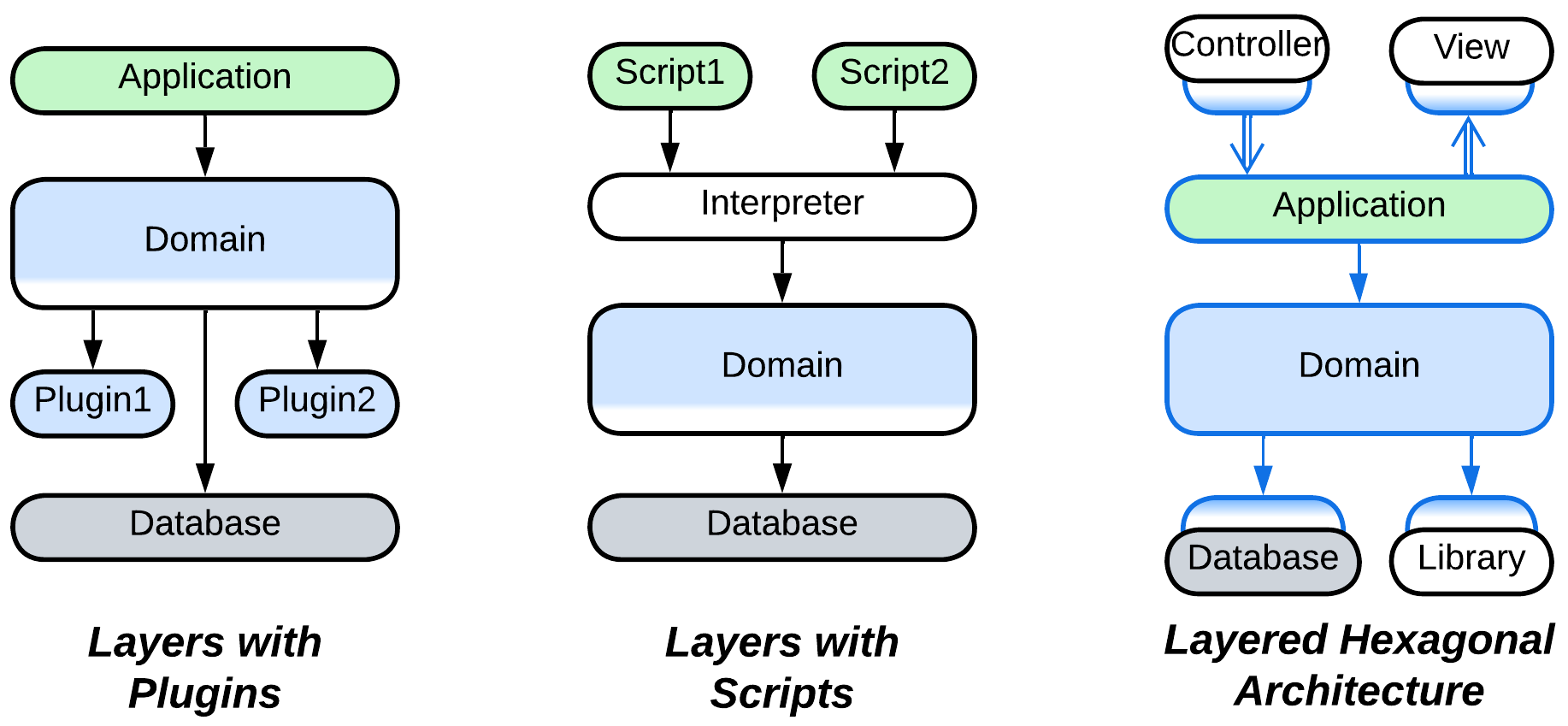

Some domains, including embedded systems and telecom, require their lower layers to be polymorphic as they deal with varied hardware or communication protocols. In that case an upper layer (e.g. OS kernel) defines a service provider interface (SPI) which is implemented by every variant of the lower layer (e.g. a device driver). That allows for a single implementation of the upper layer to be interoperable with any subclass of the lower layer. Such an approach enables Plugins, Microkernel, and Hexagonal Architecture.

There may also be an Adapter layer between your system’s SPI and an external API. It is called Anticorruption Layer [DDD], Database Abstraction Layer / Database Access Layer [POSA4] / Data Mapper [PEAA], OS Abstraction Layer or Platform Abstraction Layer / Hardware Abstraction Layer, depending on what kind of component it adapts.

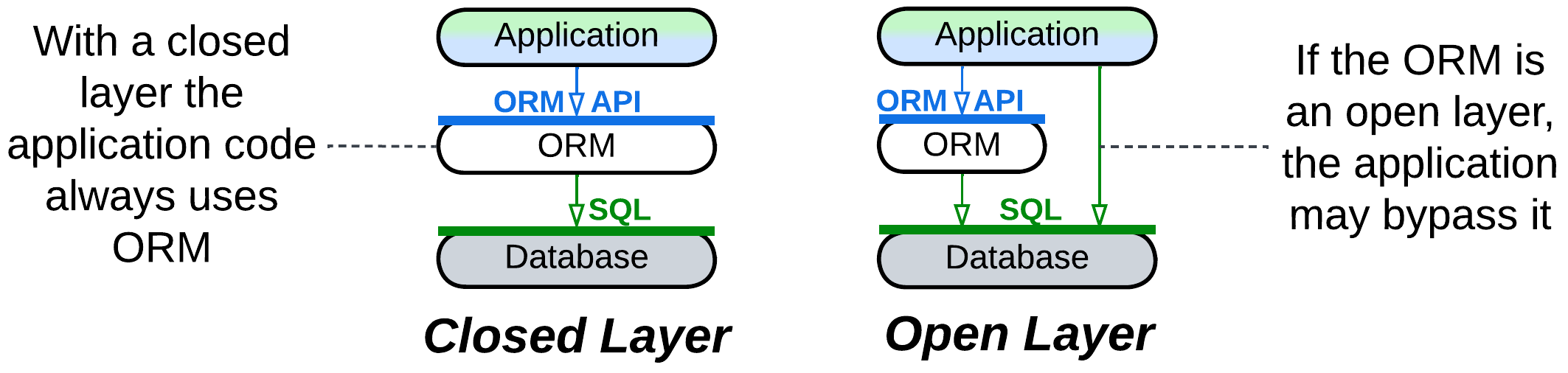

A layer can be closed (strict) or open (relaxed). A layer above a closed layer depends only on the closed layer right below it – it does not see through it. Conversely, a layer above an open layer depends on both the open layer and the layer below it. The open layer is transparent. That helps keep a layer which encapsulates one or two subdomains small: if such a layer were closed, it would have to copy much of the interface of the layer below it just to pass the incoming requests which it does not handle through to the layer below. The optimization of the open layer has a cost: the team that works on the layer above an open layer needs to learn two APIs which may have incompatible terminology.

If you ever need to scale (run multiple instances of) a layer, you may notice that a layer which sends requests naturally supports multiple instances, with the instance address being appended to each request so that its destination layer knows where to send the response. On the other hand, if there are multiple instances of a layer you call into, you need a kind of Load Balancer to dispatch requests among the instances.

Applicability #

Layers are good for:

- Small and medium-sized projects. Separating the business logic from the low-level code should be enough to work comfortably on codebases below 100 000 lines in size.

- Specialized teams. You can have a team per layer: some people, who are proficient in optimization, work on the highly loaded infrastructure, while others talk to the customers and write the business logic.

- Deployment to a specific hardware. Frontend instances run on client devices, a backend needs much RAM, the data layer demands a large HDD and security. There is no way to unite them into a single generic component.

- Flexible scaling. It is common to have hundreds or thousands of frontend instances being served by several backend processes that use a single database.

- Real-time systems. Hardware components and network events often need the software to respond within a set time limit. This is achievable by separating the time-critical code from normal priority calculations. See Hexagonal Architecture and Microkernel for improved solutions.

Layers are bad for:

- Large projects. You are still going to enter monolithic hell [MP] if you reach 1 000 000 lines of code.

- Low-latency decision making. If your business logic needs to be applied in real time, you cannot tolerate the extra latency caused by the interlayer communication.

Relations #

Layers:

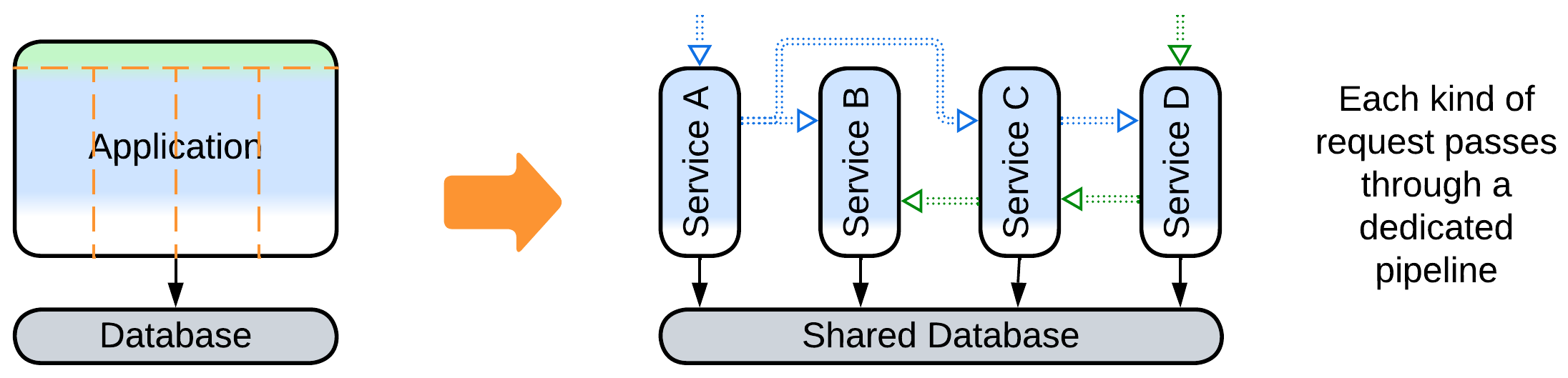

- Can be applied to the internals of any module, for example, layering Services results in Layered Services.

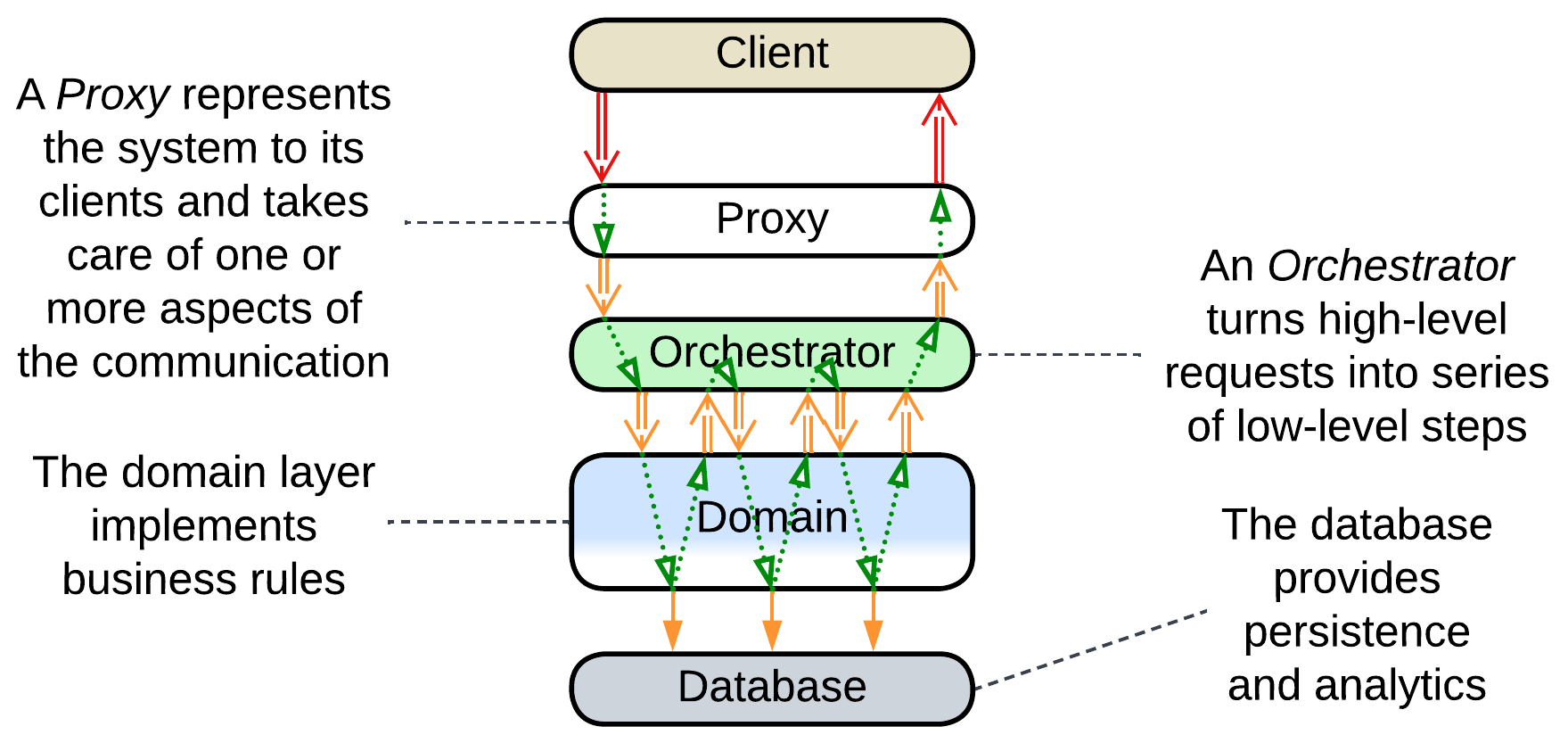

- Can be altered by Plugins or extended with a Proxy, Orchestrator, and/or Shared Repository to form an extra layer.

- Can be implemented by Services yielding layers of services present in Service-Oriented Architecture, Backends for Frontends, or Polyglot Persistence.

- May be closely related to Hexagonal Architecture or the derived Separated Presentation.

- A layer often serves as a Proxy, Orchestrator, and/or (Shared) Repository.

Variants by isolation #

There are several grades of layer isolation between unstructured Monolith and distributed Tiers. All of them are widely used in practice: each step adds its specific benefits and drawbacks to those of the previous stages until at some point it makes more sense to reject the next deal because its cons are too inconvenient for you.

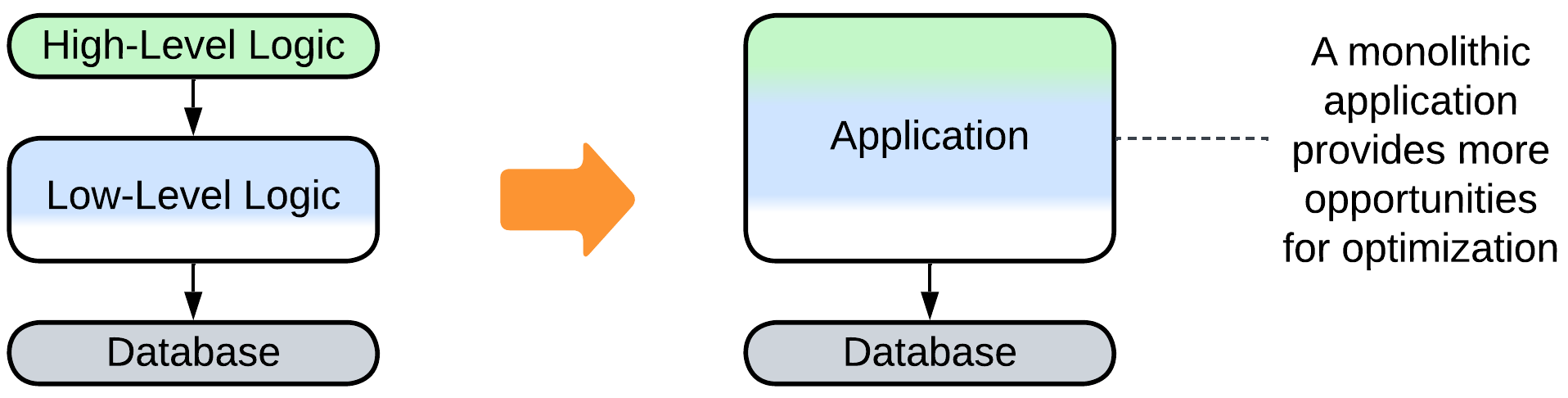

Synchronous layers, Layered Monolith #

First you separate the high-level logic from low-level implementation details. Then draw interfaces between them. The layers will still call each other directly, but at least the code has been sorted out into some kind of structure, and you can now employ two or three dedicated teams, one per layer. The cost is quite low – it is that the newly created interfaces will stand in the way of aggressive performance optimization.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Structured code | Lost opportunities for optimization |

| Two or three teams |

Asynchronous layers #

For the next step you may decide to take will be to isolate the layers’ execution threads and data. The layers will communicate only through in-process messages, which are slower than direct calls and harder to debug, but now each layer can run at its own pace – a must for interactive systems.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Structured code | No opportunities for optimization |

| Two or three teams | Some troubles with debugging |

| The layers may differ in latency |

A process per layer #

Next, you may run each layer in a separate process. You have to devise an efficient means of communication between them, but now the layers may differ in technologies, security, frequency of deployment, and even stability – the crash of one layer does not impact any of the others. Moreover, you may scale each layer to make good use of the available CPU cores. However, you will pay through even harder debugging, lower performance, and you will have to take care of error recovery, because if one of the components crashes, the others are likely to remain in an inconsistent state.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Structured code | No opportunities for optimization |

| Two or three teams | Troublesome debugging |

| The layers may differ in latency | Some performance penalty |

| The layers may differ in technologies | Error recovery must be addressed |

| The layers are deployed independently | |

| Software security isolation | |

| Software fault isolation | |

| Limited scalability |

Distributed tiers #

Finally, you may separate the hardware which the processes run on – going all out for distribution. This allows you to fine-tune the system configuration, run parts of the system close to its clients, and physically isolate the most secure components, with your scalability limited only by your budget. The price is paid in latency and debugging experience.

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| Structured code | No opportunities for optimization |

| Two or three teams | Even worse debugging |

| The layers may differ in latency | Definite performance penalty |

| The layers may differ in technologies | Error recovery must be addressed |

| The layers are deployed independently | |

| Full security isolation | |

| Full fault isolation | |

| Full scalability | |

| Layers vary in hardware setup | |

| Deployment close to clients |

Examples #

The notion of layering seems to be so natural to our minds that most known architectures are layered. Not surprisingly, there are several approaches to assigning functionality to and naming the layers:

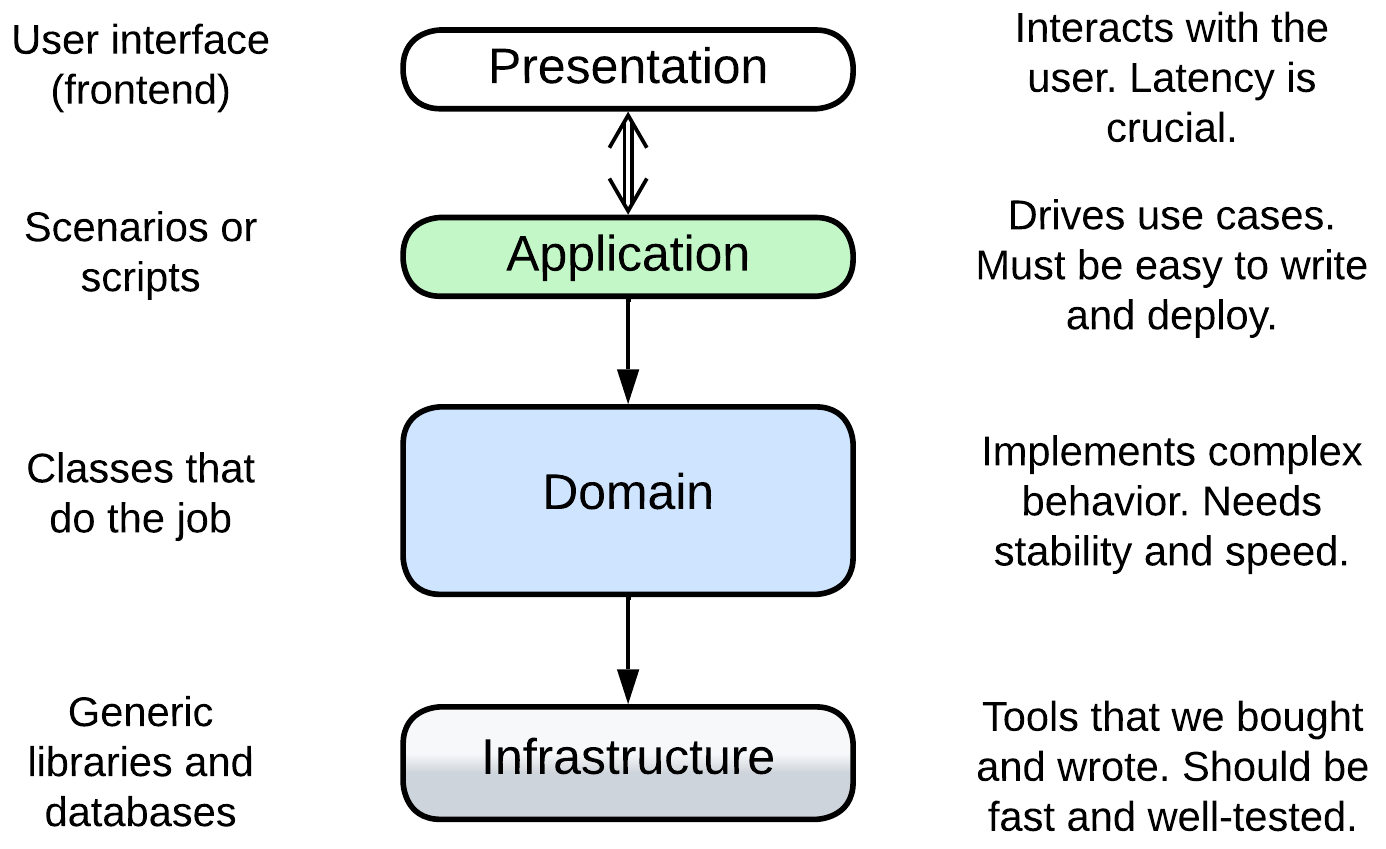

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) Layers #

[DDD] recognizes four layers with the upper layers closer to the user:

- Presentation (User Interface) – the user-facing component (frontend, UI). It should be highly responsive to the user’s input. See Separated Presentation.

- Application (Integration, Service) – the high-level scenarios which build upon the API of the domain layer. It should be easy to change and to deploy. See Orchestrator.

- Domain (Model, Business Rules) – the bulk of the mid- and low-level business logic. It should usually be well-tested and performant.

- Infrastructure (Utility, Data Access) – the utility components devoid of business logic. Their stability and performance is business-critical but updates to their code are rare.

For example, an online banking system comprises:

- the presentation layer which is its frontend;

- the application layer which implements sequences of steps for payment, card to card transfer, and viewing a client’s history of transactions;

- the domain layer contains classes for various kinds of cards and accounts;

- the infrastructure layer with a database and libraries for encryption and interbank communication.

However in practice you are much more likely to encounter the derived DDD-style Hexagonal Architecture than the original DDD Layers.

We will often use the DDD naming convention while describing more complex architectures, some of which have all the four layers, while others merge several layers together or omit the frontend and concentrate on the components that contain the business logic.

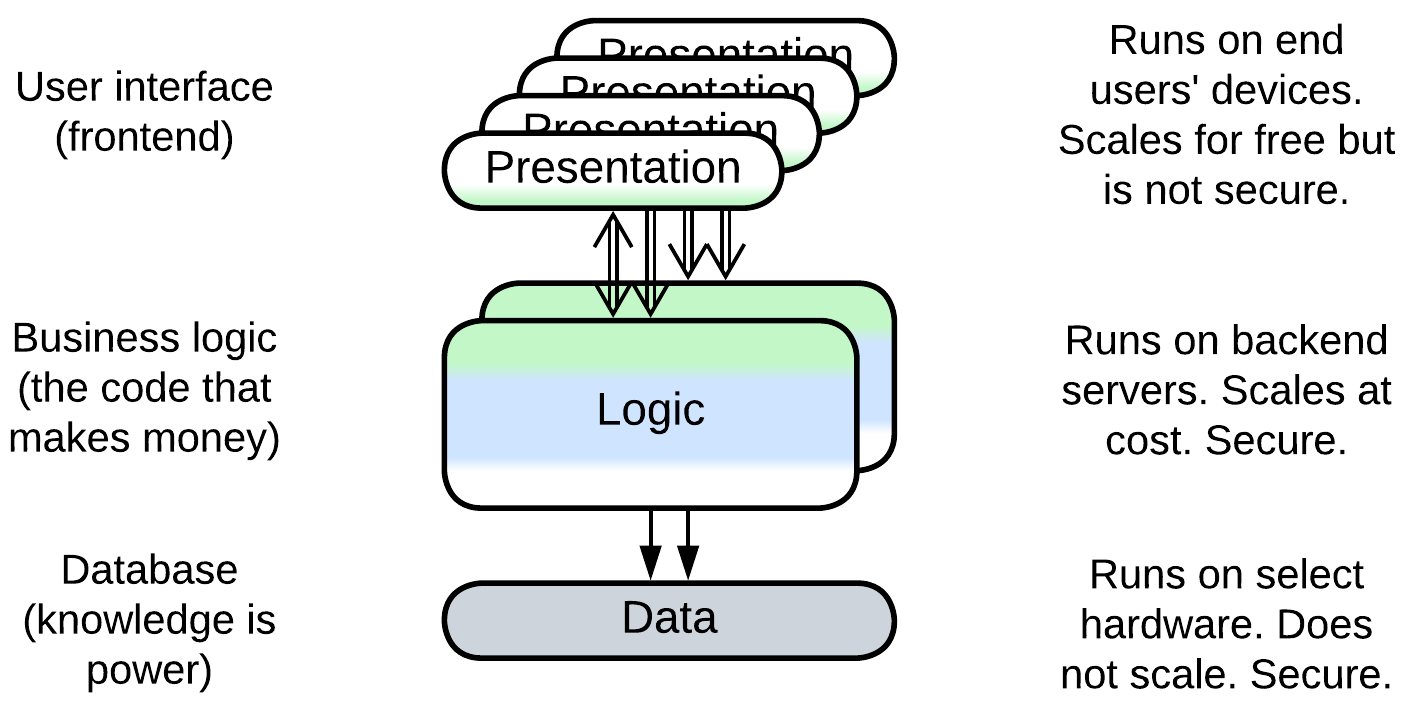

Three-Tier Architecture #

Here the focus lies with the distribution of the components over heterogeneous hardware (Tiers):

- Presentation (Frontend) tier – a user-facing application which runs on a user’s hardware. It is very scalable and responsive, but insecure.

- Logic (Backend) tier – the business logic which is deployed on the service provider’s side. Its scalability is limited mostly by the funding committed, security is good but latency is high.

- Data (Database) tier – a service provider’s database which runs on a dedicated server. It is not scalable but is very secure.

In this case the division into layers resolves the conflict between scalability, latency, security, and cost as discussed in detail in the chapter on distribution.

Tiers don’t map to Layers directly. For example, a protocol support library which is used for communication between services belongs to the lowest (infrastructure) layer but to the middle (backend) tier. The discrepancy is rooted in different natures (views of the 4+1 model) of the patterns in question: Layers show the logical composition of the system while Tiers deal with its physical structure (deployment).

Embedded systems #

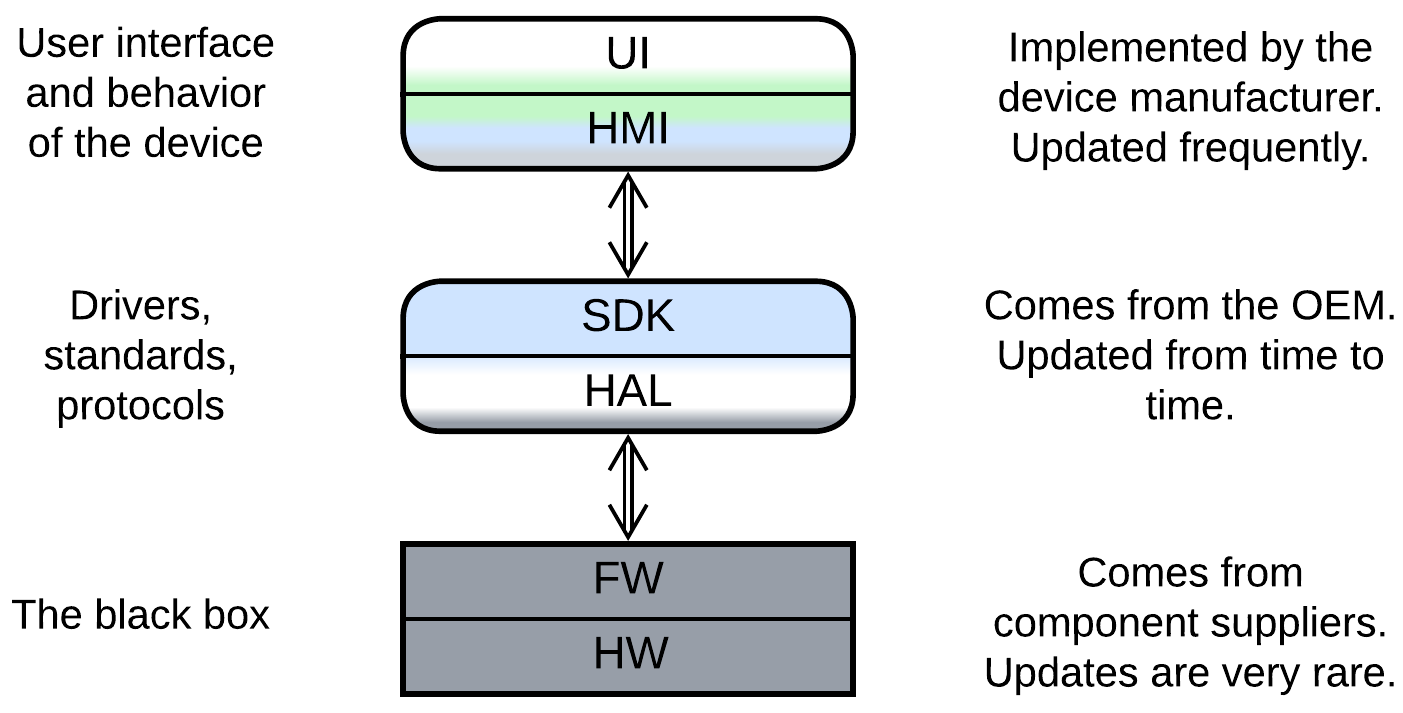

Bare metal and micro-OS systems which run on low-end chips use a different terminology, which is not unified across domains. A generic example involves:

- Presentation – a UI engine used by the HMI. It may be a third-party library or come as a part of the SDK.

- Human-Machine Interface (HMI aka MMI) – the UI and high-level business logic for user scenarios, written by a value-added reseller.

- Software Development Kit (SDK) – the mid-level business logic and device drivers, written by the original equipment manufacturer.

- Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) – the low-level code that abstracts hardware registers to enable code reuse between hardware platforms.

- Firmware of Hardware Components – usually closed-source binary pre-programmed into chips by chipmakers.

- Hardware itself.

It is of note that in this approach the layers form strongly coupled pairs. Each pair is implemented by a separate party of the supply chain, which is an extra force that shapes the system into layers.

An example of such a system can be found in an old mobile phone or a digital camera.

Evolutions #

Layers are not without drawbacks which may force your system to evolve. A summary of such evolutions is given below while more details can be found in Appendix E.

Evolutions that make more layers #

Not all the layered architectures are equally layered. A Monolith with a Proxy or database has already stepped into the realm of Layers but is far from reaping all its benefits. Such a system may continue its course in a few ways that were previously discussed for Monolith:

- Employing a database (if you don’t use one) lets you rely on a thoroughly optimized state-of-the-art subsystem for data processing and storage.

- Proxies are similarly reusable generic modules to be added at will.

- Implementing an Orchestrator on top of your system may improve programming experience and runtime performance for your clients.

It is also common to:

- Have the business logic divided into two layers.

Evolutions that help large projects #

The main drawback (and benefit as well) of Layers is that much or all of the business logic is kept together in one or two components. That allows for easy debugging and fast development in the initial stages of the project but slows down and complicates work as the project grows in size [MP]. The only way for a growing project to survive and continue evolving at a reasonable speed is to divide its business logic into several smaller, thus less complex, components that match subdomains (bounded contexts [DDD]). There are several options for such a change, with their applicability depending on the domain:

- The middle layer with the main business logic can be divided into Services leaving the upper Orchestrator and lower database layers intact for future evolutions.

- Sometimes the business logic can be represented as a set of directed graphs which is known as Event-Driven Architecture.

- If you are lucky, your domain makes a Top-Down Hierarchy.

Evolutions that improve performance #

There are several ways to improve the performance of a layered system. One we have already discussed for Shards:

- Space-Based Architecture co-locates the database and business logic and scales both dynamically.

Others are new:

- Merging several layers improves latency by eliminating the communication overhead.

- Scaling some of the layers may improve throughput.

- Polyglot Persistence is the name for using multiple specialized databases.

Evolutions to gain flexibility #

The last group of evolutions to consider is about making the system more adaptable. We have already discussed the following evolutions for Monolith:

- The behavior of the system may be modified with Plugins.

- Hexagonal Architecture allows for abstracting the business logic from the technologies used in the project.

- Scripts allow for customization of the system’s logic on a per client basis.

There is one new evolution which modifies the upper (orchestration) layer:

- The orchestration layer may be split into Backends for Frontends to match the individual needs of several kinds of clients.

Summary #

Layered architecture separates the high-level logic from the low-level details. It is superior for medium-sized projects as it supports rapid development by two or three teams, is flexible enough to resolve conflicting forces, and provides many options for further evolution, which will come in handy when the project grows in size and complexity.