Four kinds of software #

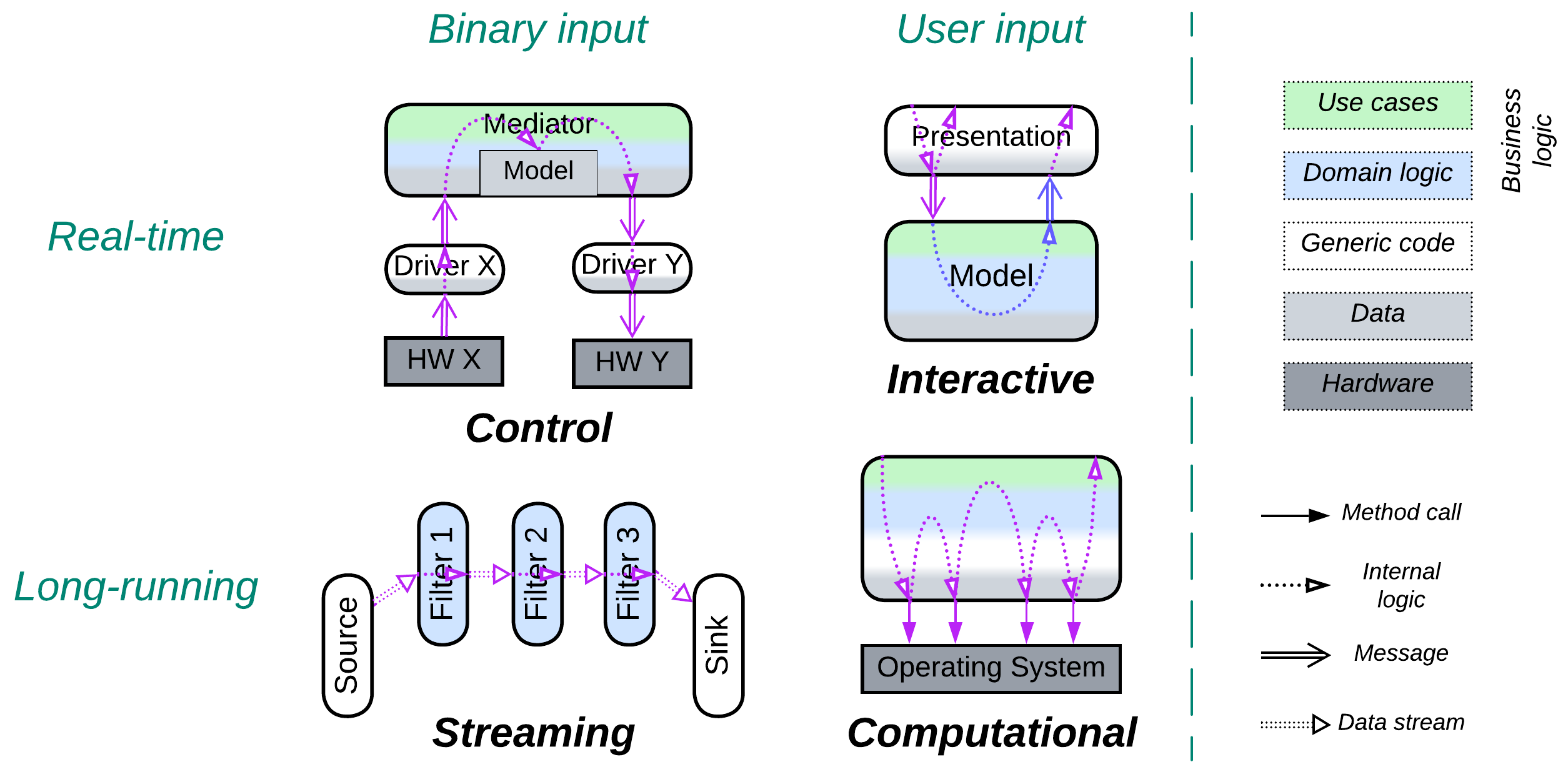

Software products vary in their goals which, surprisingly, determine their structure and operation. The main features of software make a fuzzy continuous space rather than a strict set of well-defined classification options. Let’s examine two of its dimensions:

Source of inputs #

Some systems receive their inputs from users via text commands or UI controls, often mediated by a network protocol. Such inputs are highly meaningful, structured and compact – processing a single user command often invokes a larger part of the program’s functionality.

Another kind of system deals with binary data or signals that come from hardware. Those input sources have low informational payload – a digitized movie is orders of magnitude larger than a book written in a human language and still omits many details of the original text. Raw inputs often require context (the program’s state) to understand their meaning: the same sequence of bits may be treated as a part of a video, audio, executable file or archive – and the correct interpretation is known only from the command your program is running and the name and header of the file it is processing.

Latency constraints #

Programs that control hardware or interface with users need to respond to their inputs in real time. Milliseconds of delay result in any kind of bad stuff that ranges from negative reviews and lost business opportunities to lost human lives (which are the same from the business PoV). That kind of software can never block its execution or run long calculations and has to keep all the data involved in memory.

Other programs are not that time-constrained – they run a single task for a long time, accessing many files or consulting remote services in the process. They may use more powerful decision-making algorithms and all the data in the world – but they are slower to respond.

Those dimensions make four corner cases that vary in architectural styles:

Control (real-time, hardware input) #

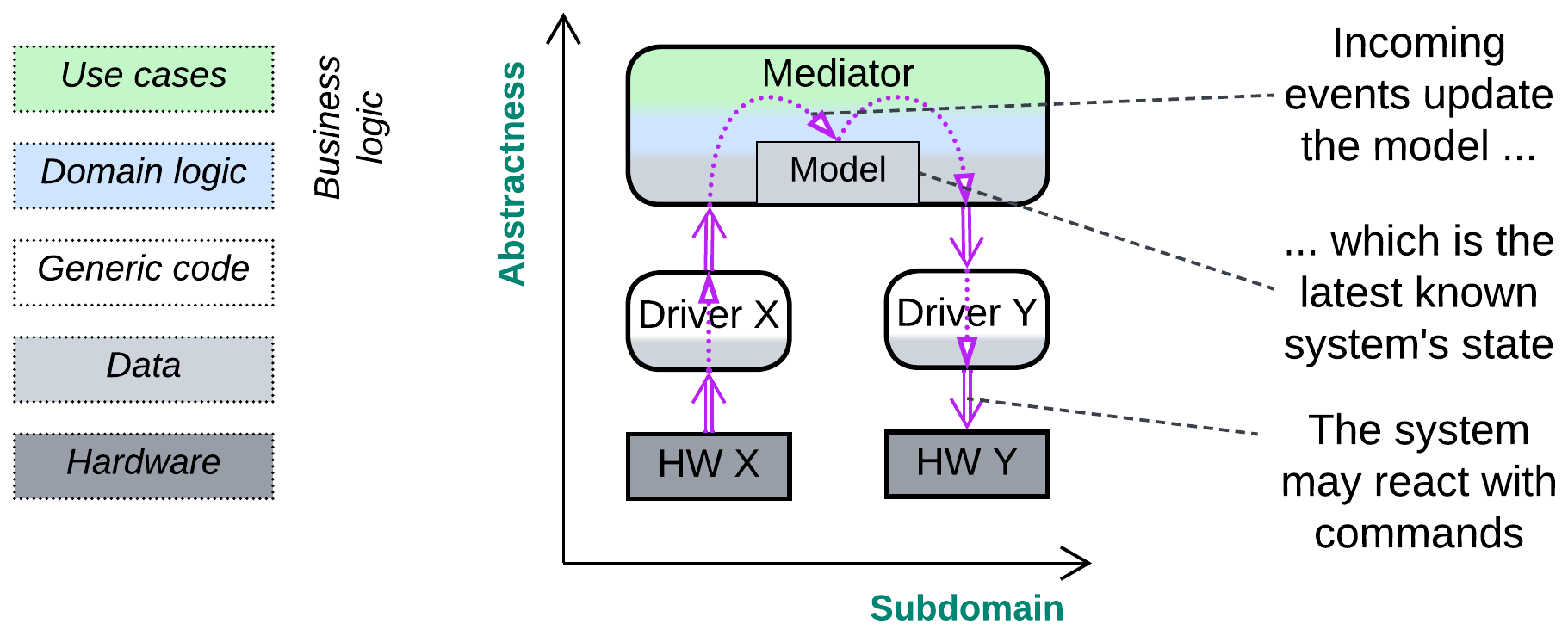

A control application supervises several hardware or software interfaces with the goal of keeping a certain system-wide invariant:

- A fly-by-wire program receives readings from the airplane’s sensors and adjusts its actuators to keep the vehicle on its course, which is the invariant.

- When a telephony gateway receives an outgoing call request from one of the devices that it manages, it checks the dialed number, initiates an incoming call to a matching interface, and connects a voice channel between the devices as soon as the destination accepts the call. The invariant is that calls live in pairs: if a call comes in, it is to be rejected or a derived call should go out of the device.

- A Container Orchestrator checks the health of the services it manages and restarts any one which is slow to respond to its keep-alive request, making sure that all the services are online.

As a control software must react quickly, it has no time to read from storage or obtain from other components the data it needs to make decisions. Thus it has to build and maintain in its memory a model of the system it controls:

- An autopilot knows the last measured plane’s coordinates, speed, angles and states of all its actuators.

- A telephony application models both the phones and accounts it supervises and the calls present in the system.

- A container manager remembers the state of every service it oversees, the time of the last health check and user request statistics (number of requests and processing time).

When a program receives information from a component it controls, it updates its in-memory model with the new data and checks if the target invariant still holds:

- A plane should remain on its course, otherwise its angles or thrust must be adjusted.

- If there is a new incoming call, a VoIP gateway must create a corresponding outgoing call.

- If a service is known to have not responded for a while, it must be killed and restarted.

After the compensating action is initiated, the model is updated accordingly, and the software resumes processing events. After a while it should receive events that confirm that the invariant was restored:

- The new sensor readings will show that the plane is back on its course.

- The outgoing call will have been accepted and the gateway will connect the voice path between the call parties.

- The container will have been restarted successfully and will be serving user requests.

The flow of changes through the system is M-shaped: it starts as a low-level event, gets interpreted by a hardware driver or protocol stack, and goes up to an Orchestrator, which updates its model and decides if there should be any reaction, which would then go all the way down to the same or another low-level interface.

Variants #

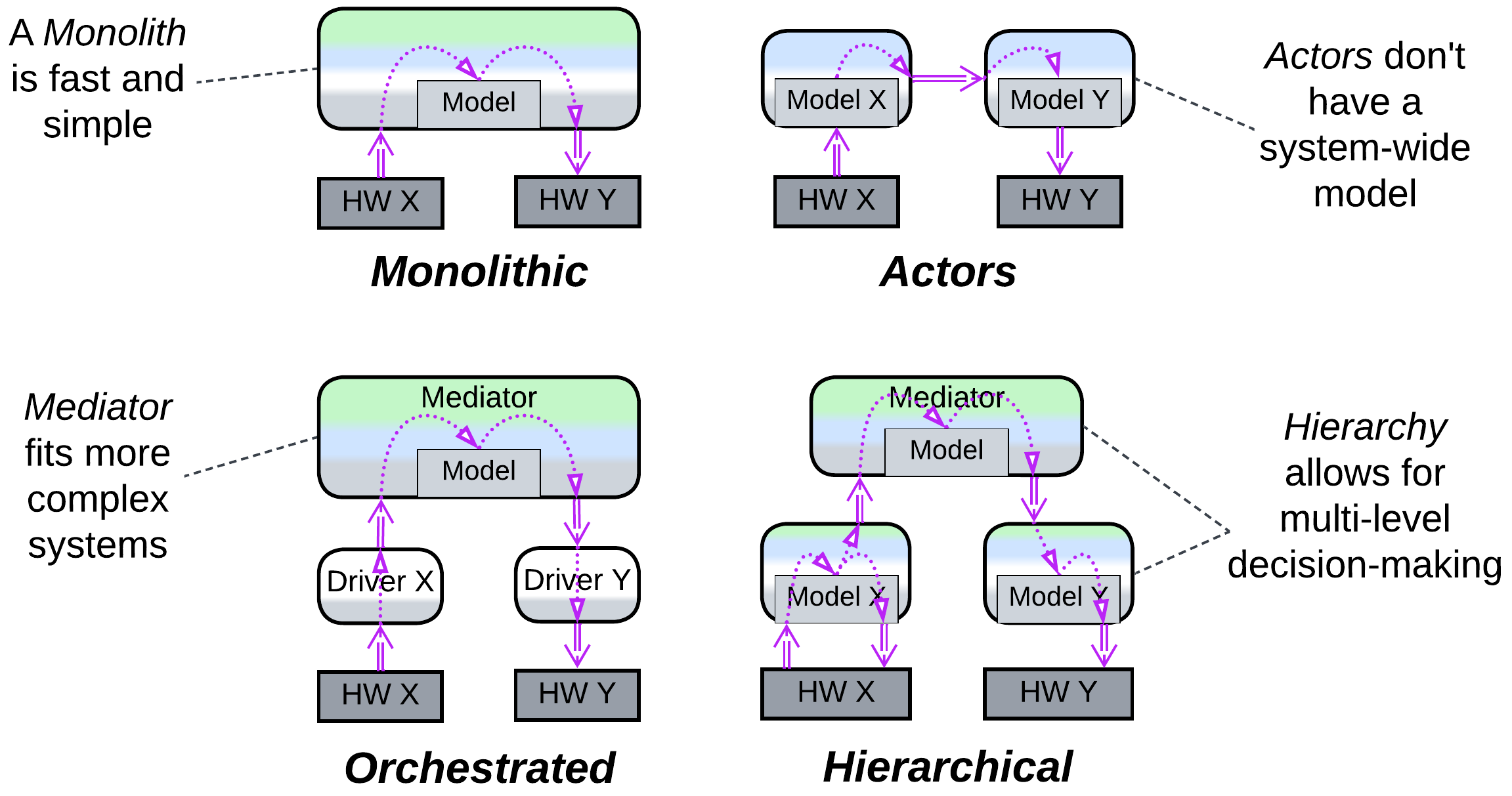

At the architectural level, control systems are event-driven – their components communicate by messages. There are several architectures I am aware of:

- Monolith is the simplest and fastest implementation, usually tiny enough to run everything in a single super loop.

- Plain (choreographed) Actors fit systems of trivial logic but massive scale, like messenger backends. Each actor models the component (remote device or user) it interacts with, and there is no global model except for a registry of actors.

- Orchestrated modules are a better solution for complicated (cohesive) systems that need centralized management. The Orchestrator contains the whole system’s model and integration logic.

- A Hierarchical Orchestrator can manage even more complex systems. The Orchestrator may run synchronously with polymorphic specialized components or asynchronously. In the last case each sub-orchestrator reacts independently based on its own model but also sends a notification to the high-level component which builds a global strategy and programs the smaller models of sub-orchestrators.

Patterns #

The following patterns are prominent in control software:

- Actors – partitioning the domain into self-consistent asynchronous entities allows fine control over the order of execution of system activities, provided that we run a preemptive scheduler (from POSIX real-time threads or RTOS) – we can assign top priority to reading data from communication interfaces (which would quickly overflow if the data is not retrieved), make reacting to events a bit less urgent, and still have leftovers of our CPU time for such long-running tasks as file access or strategic planning.

- Proactor [POSA2, POSA4] – almost every component is single-threaded, reactive, and non-blocking, which makes the system very responsive. The downside is being unable to represent a multi-step scenario as a single function, which is usually unimportant as no predefined scenario ever survives event-driven reality unshattered. Following a planned path leads directly to your grave. Proceed stepwise, checking for dangers every millisecond, being ready to jump away from any approaching trouble.

- Mediator [GoF] (a kind of Orchestrator) – when you rely on information from and manage several devices or interfaces, you need a single entity that knows what is going on, makes informed decisions and dispatches commands to be executed. It integrates all the lower-level components into a coherent system. It is a Mediator.

- Hexagonal Architecture – hardware components quickly become obsolete, and if you want your software to survive for a decade, you must be able to change them at will. And if you want to run, test, and debug your code on your desktop, you often need to stub or mock the hardware.

- Hierarchy – if you manage a variety of interfaces that have the same role (telephony protocols, account providers, or payment systems) you want to make them polymorphic towards your main application logic. In other cases, like IIoT, you may need to start reacting immediately with little precision and correct your actions after you have spent more time on better planning, which is achieved through a hierarchy of feedback loops.

Implementation #

In the code we may (or may not) see State [GoF] (aka Objects for States [POSA4]) close to hardware or protocol interfaces, but the higher-level logic is likely to depend on multiple parameters which would make too many combinations to write down as state classes, thus it tends to be coded as a decision tree instead.

System components (Actors) have private in-memory data and communicate only by messages. They are usually single-threaded and non-blocking (Proactor) – this way, the only locks in the system are those protecting the actors’ message queues and the global memory manager, which don’t contain anything complicated to block on for a noticeable time. And as nothing ever blocks, the whole system is extremely responsive.

Messages may be dispatched through multilevel index arrays or Visitors [GoF]. Message queues may be shared (a queue per thread priority) or private (a queue per component). With shared queues the destination of a message must either be resolvable from its type (when there is a single instance of every kind of system component) or stored in the message’s header.

Interactive (soft real-time, user input) #

An interactive software deals with users who expect it to provide immediate feedback to their actions. Examples include:

- Desktop and mobile applications, from text editors to browsers.

- Simple games, like chess or tetris.

- UI of embedded devices, such as clocks or air conditioning systems.

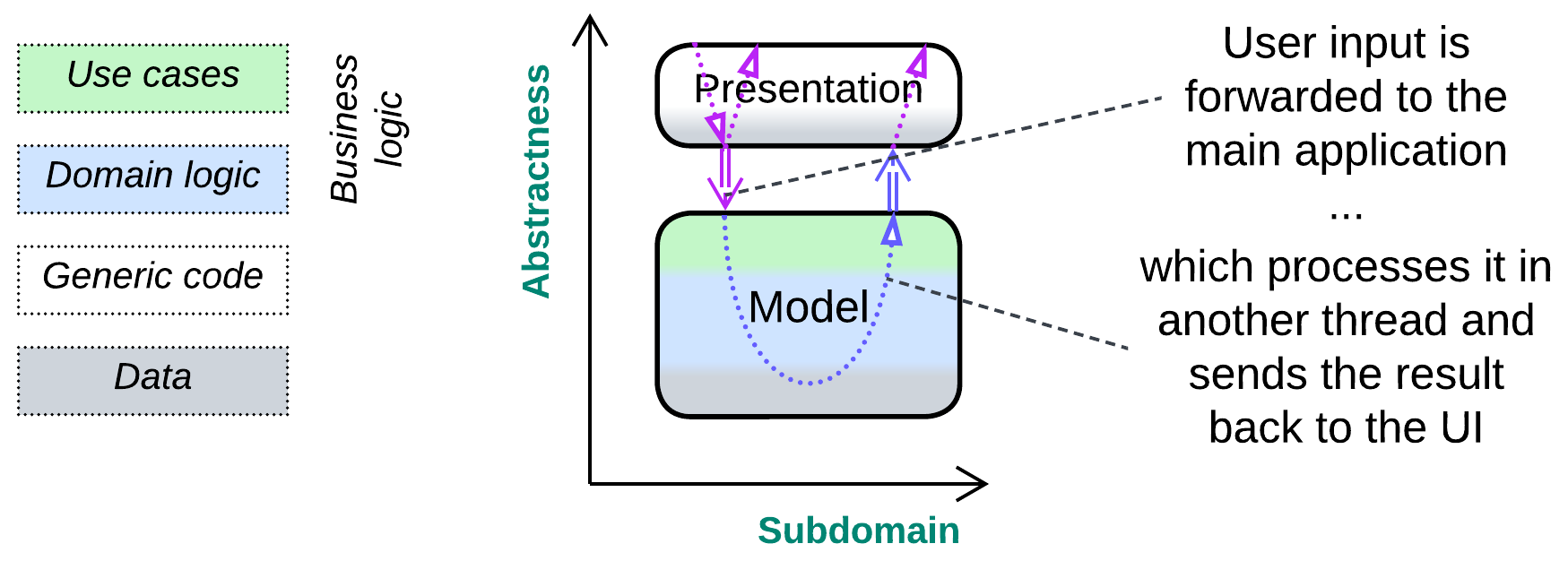

The user interface layer (Separated Presentation) receives input (mouse, keyboard, or touchscreen events), interprets it as a user action based on the current application’s state (pressing enter in a text editor may break a line of text in two, begin a new line or even activate a menu item), forwards the action to the lower levels of the software and displays any feedback received, producing a U-shaped flow.

Variants #

Interactive systems vary in a couple of ways:

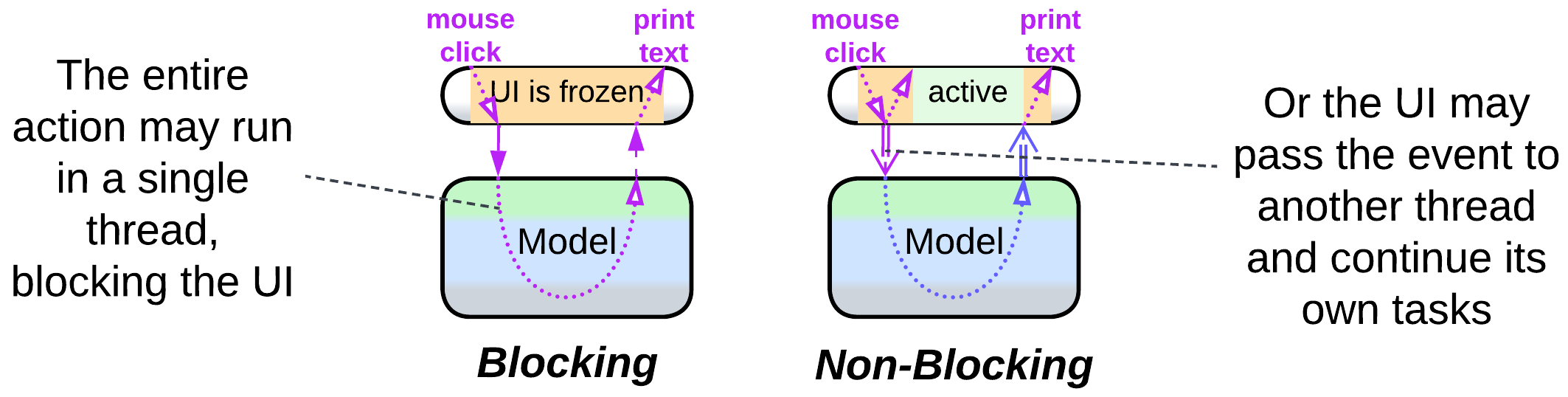

- The presentation layer may wait for the business logic to execute the user’s action, blocking further user input and screen updates (air conditioner controller), or it may asynchronously pass the command to the lower layer and continue processing new user input and showing progress of the already running tasks (many games) while the main program is busy with the command.

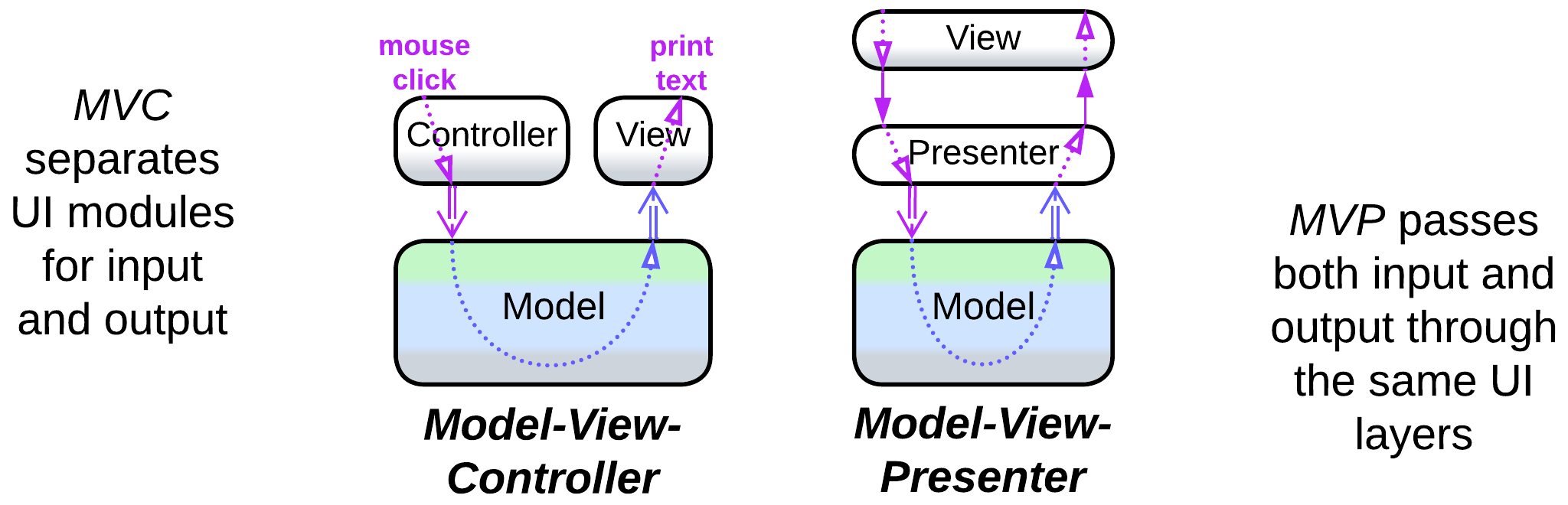

- There may be dedicated modules for processing user input and output (MVC family of patterns) or both may pass through the same stack of components (MVP family). The asymmetric approach deals with raw controller input, which is what most games need, while the bidirectional flow operates UI widgets provided by the host OS or GUI framework.

Patterns #

You will likely encounter:

- Separated Presentation – the business logic is unaware of the implementation of the UI layer, though this may not be the case with some games that rely on game development frameworks. This pattern is usually implemented by:

- Model-View-Presenter (MVP) – two input layers, namely: view which receives input and shows output and presenter which translates between the business logic, called model, and the view.

- Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) also has two layers, but the intermediate ViewModel binds to the view and bears its state.

- Model-View-Controller (MVC) [POSA1, POSA4] separates the input (controller) from the output (view).

- State [GoF], subclassed by [POSA4] into Objects for States, Methods for States, and Collections for States, is prominent in games, though it may not always be implemented explicitly.

- Flyweight, Command, Observer and many other [GoF] patterns originated with desktop software and may often appear in games.

Implementation #

The presentation layer may be called into by the desktop environment or it may run in a dedicated thread, for example, to play animations.

The business logic is likely to rely on its own threads, at least for long-running actions.

The presentation would usually subscribe to updates from the business logic.

Streaming (continuous, raw data input) #

A streaming system processes a long sequence of similar events or data packets, usually by transforming individual items in a predetermined way:

- Each party in an audio call or video conference deals with incoming and outgoing media streams. For example, incoming audio stream processing involves: saving audio packets to a jitter buffer to restore their order, compensation for lost packets, decoding, equalization, and playback. Outgoing audio passes through the following steps: echo suppression or cancelation, noise reduction, equalization, encoding, adding network headers, and sending packets to the network.

- An image recognition system applies a long sequence of transformations to every input image.

- Hardware often works with streams. For example, a CPU instruction pipeline comprises at least: instruction fetching, instruction decoding and register fetching, execution, memory access, and register writeback. High-end processors may have up to 20 stages.

- Many UNIX command-line tools process streams of lines of text, allowing for complex text processing by chaining pre-existing utilities [DDIA].

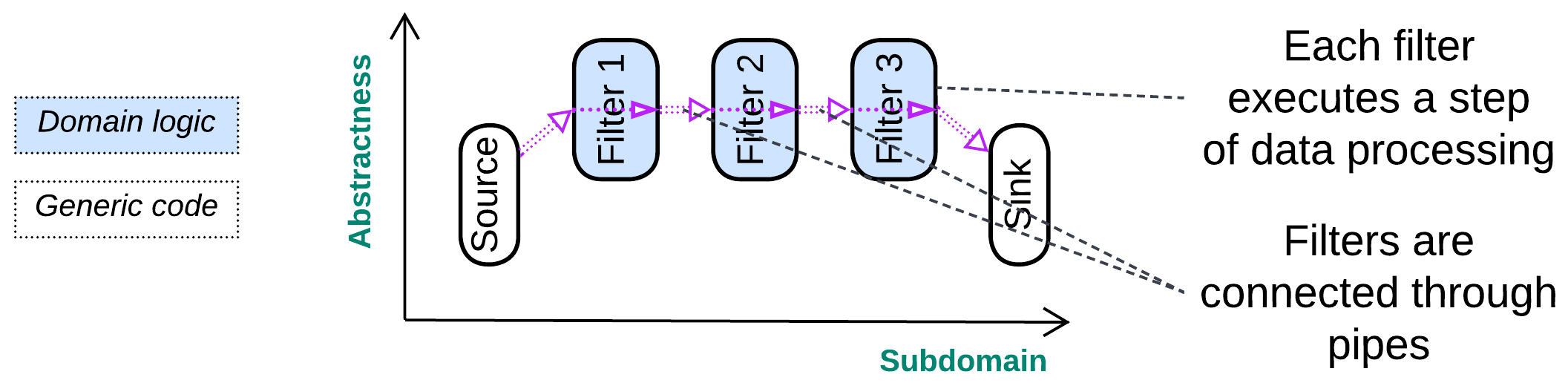

Streaming usually passes data through a chain of transformations (pipeline) which differ in functionality but stay at about the same level of abstractness – there are no managers or hierarchy. Such a –-shaped structure allows for all the specialized components to deal with their chunks of the stream in parallel, which increases the system’s throughput but suffers from moderate to high latency.

Variants #

As stream-processing Pipelines can exploit multiple CPU cores and specialized hardware, they are found everywhere from lowest-level firmware to large-scale distributed systems. [DDIA] classifies them into:

- Stream processing, where the pipeline is always alive waiting for more input to come.

- Batch processing, where the pipeline runs till it finishes processing an input file.

Patterns #

-

Pipes and Filters [POSA1, POSA4] is the stream processing pattern that describes pipelines: the system is built of filters (individual data processing steps) connected through pipes (data channels).

-

Choreographed Event-Driven Architecture (EDA) [SAP, FSA, DDS] and Data Mesh [LDDD, SAHP] are tree-like pipelines that process streams of domain events or data, correspondingly.

[EIP] is full of patterns for the distributed processing of event streams.

Implementation #

Every filter is likely to run in its own thread and be unaware of other filters – it only knows where to pull its input from and push its output into. One common challenge is to slow down a too fast data producer or scale data consumers when too much intermediate data accumulates in the pipe between them.

Computational (single run, user input) #

Finally, there is a large group of applications created to process long-running commands:

- A scientific calculation runs for days or weeks to provide insight into the physical reality or validate a new theory.

- A compiler creates a platform-specific binary by processing text files with the program’s code.

- An interpreter runs scripted actions on its user’s behalf.

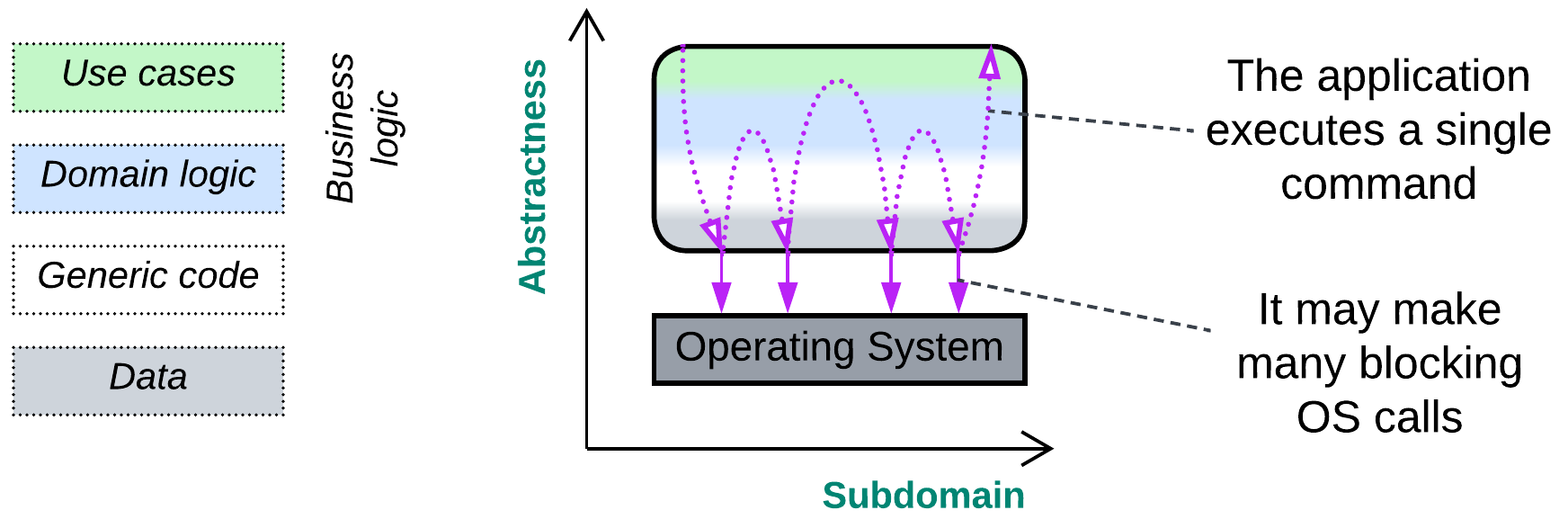

In each case the application starts with parsing (interpreting) its input, proceeds to execute it in a stepwise (and likely looped) manner and finishes by outputting results of the run, making a W-shaped flow.

Variants #

Some computational systems are single-use with a hard-coded task (calculation of Pi) while others can execute a variety of user scenarios (script interpreters).

Patterns #

Long-running programs with user input are probably the most common, ancient, and well-studied kind of software, which also inspired many design patterns. Those of special significance are:

- Interpreter [GoF] that supports very complex user commands.

- Facade [GoF] or Process Manager [EIP] (kinds of Orchestrator) that executes a user command as a sequence of calls to lower-level components.

Implementation #

You likely have some kind of parser (complex for SQL or very simple for command-line parameters) that transforms user input into a syntax tree or a set of flags, correspondingly. Then there is a kind of main loop which iteratively executes actions, pre-defined or encoded in the parsed tree, until an exit condition is met or the entire input has been processed.

Any calls to external components (OS or libraries) are likely to be blocking as the computation does not need to react quickly to any additional input – actually, it does not read any input or change its behavior for the entire duration of its run.

Parts of computations may be offloaded to SIMD or GPU/TPU because that greatly speeds up number crunching which is often characteristic of long-running calculations.

Mixed cases #

Most real-life software is too complex to fit the classification outlined above. It tends to merge the paradigms either by mixing them to find a middle ground or by implementing two or three of them at once. Let’s inspect a few random examples to see how that happens:

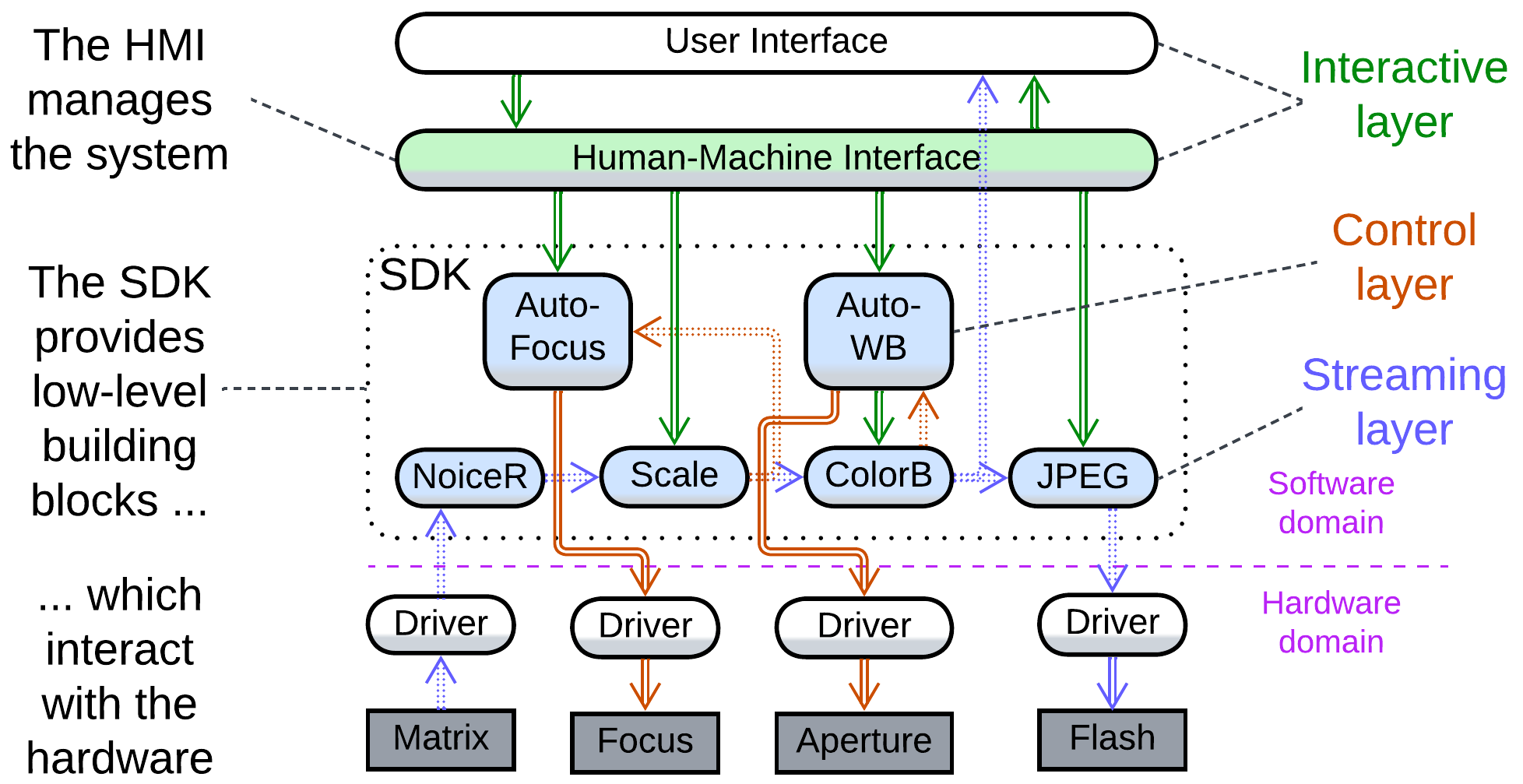

Camera #

A digital camera incorporates subsystems of different kinds:

- There is an interactive user interface that receives commands for other components and displays either the video stream from the matrix or the camera’s settings menu.

- A control layer provides feedback loops to keep the camera focused on a selected object and preserve the overall brightness level and color balance when shooting in automatic mode.

- An image processing pipeline applies noise reduction, rescaling, and color correction, then either passes the resulting frames to the UI to show them on the screen or proceeds with compressing the frame and storing it as a file.

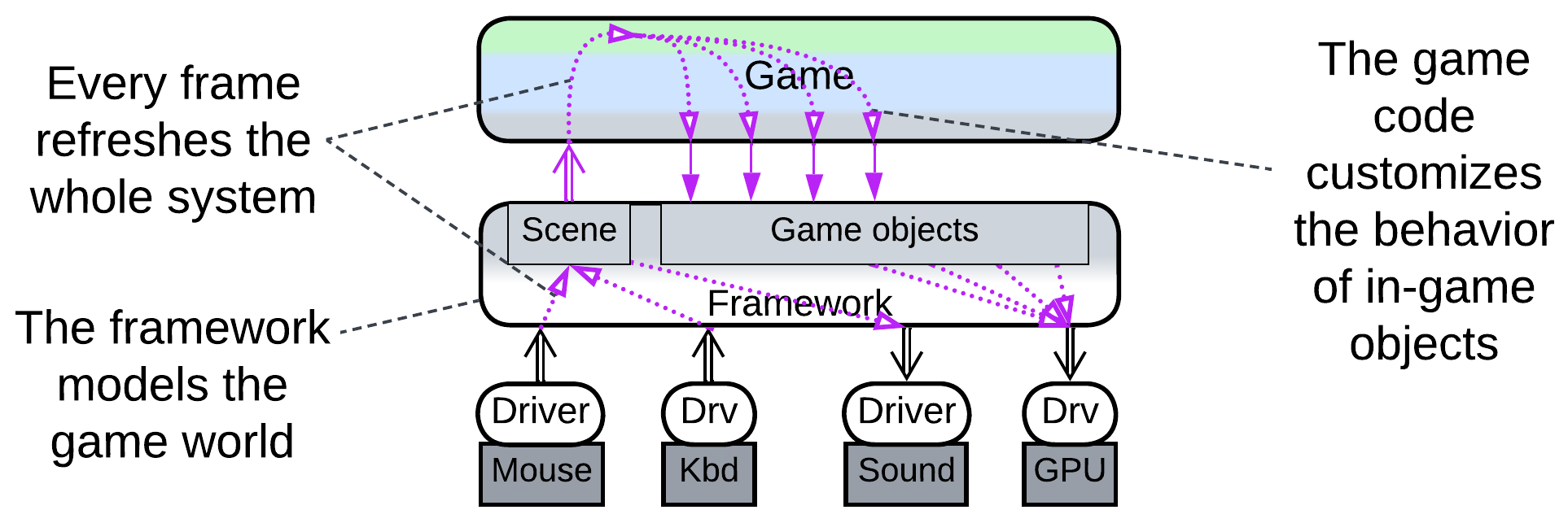

3D action game #

Games with 3D graphics often bypass the host OS’ desktop environment and access the underlying hardware drivers to achieve fine control and improved performance. Such applications, though pretending to be interactive software driven by user input, strongly resemble control systems by polling hardware with fixed frequency (the game’s frame rate).

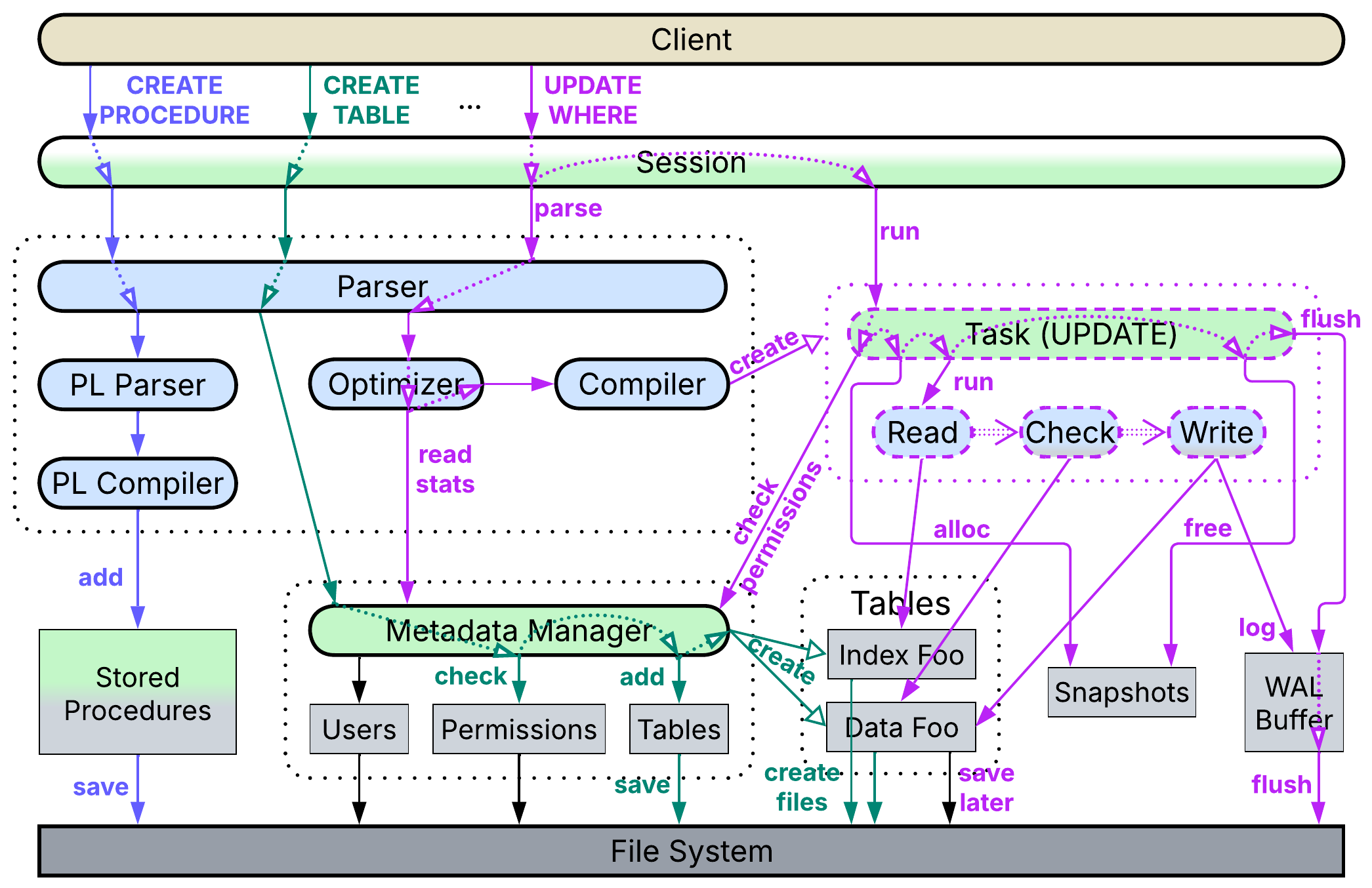

SQL database #

SQL databases support several kinds of user commands:

- Data definition and data control languages (DDL / DCL) manage the database’s metadata: table definitions and user permissions, correspondingly.

- Data manipulation and data query languages (DML / DQL) write to and read from the tables.

- Procedural language (PL) programs user-defined functions (stored procedures).

Each kind of command is processed in a unique way:

- When the parser recognizes a DDL or DCL request, it calls a corresponding method that reads or modifies the metadata. If a table is to be altered, the action will either lock the table for the duration of operation or require a complicated workaround to allow other sessions to access the table while it is being restructured.

- DML or DQL input is compiled into a tree of elementary operations (reads, conditions, joins, etc.) which is then passed to the query optimizer to be rearranged into a linear sequence of operations that accounts for table sizes and index types. The execution of the resulting pipeline depends on its type:

- As a query (DQL) does not change anything, it merely reserves a virtual snapshot of the current state of the tables, runs the compiled pipeline on the snapshot (probably taking quite a while), streams the output to the client and, finally, releases the snapshot.

- Commands (DML) modify data, thus they involve a few extra steps. A snapshot is allocated as well, however, now it is writable, storing all the changes to the database the command’s pipeline makes. Every change is also written to a Write-Ahead Log (WAL) buffer. When the pipeline or a wrapping transaction completes, the database engine ensures that the data changed in the snapshot is still unchanged in the main database. In case of a conflict the snapshot and WAL buffer are dropped, a new snapshot is allocated on top of the conflicting changes in the main storage, and the command is re-applied. As soon as there are no conflicts, the WAL buffer is flushed to the WAL file, which is the single source of truth for the database’s crash recovery. After that the changes from the snapshot are integrated into the main data storage, marking any updated data structures as dirty. The snapshot and WAL buffer are released, the command returns the number of rows it changed to the user, and another background thread lazily flushes the dirty data to the file system or network storage.

Snapshotting (MVCC) allows long-running queries (OLAP) to return consistent data (without reporting any concurrent changes from commands) and commands (OLTP) to commit with no need to lock database records.

- PL requests are identified by keywords and forwarded to a PL-dedicated parser which checks their syntax, compiles the user-defined functions into some kind of pseudocode and stores them for further use by queries or commands.

Here we have:

- Dynamically created streaming pipelines that represent DQL and DML requests.

- Heavy reliance on parsers and compilers, like in computational software.

- A long-running main application that deals with multiple user requests that often need to be executed quickly, like in interactive applications.

[DDIA] is dedicated to the implementation of databases, which are indeed way more complex and varied than what I outlined above.

Summary #

We can discern four kinds of systems that differ in their goals, architecture, and code:

- Control – supervises hardware and must react with extremely low latency. It never blocks and relies on an in-memory model of the system it manages.

- Interactive – deals with users, should handle their actions and provide feedback in near real time. Its user-facing layer tends to be separated from the main logic.

- Streaming – processes boring sequences of data items. Such systems are usually assembled from single-purpose components.

- Computational – performs a long-running calculation. It parses user input to understand its task, then goes deep into its engine to execute it and, finally, pops up the result.

Complex real-world software usually involves two or three of these approaches.