Forces, asynchronicity, and distribution #

Many systems rely on asynchronous communication between their components or are distributed over a network. Why is dividing a system into modules or classes then not enough in real life?

Requirements and forces #

Any software is built to meet a set of (explicit or implicit) requirements. As a bare minimum, you as a programmer must have at least a vague vision of how your software is expected to operate. At the most, business analysts bring you volumes of incomprehensible documentation they wrote for the sole purpose of forcing you to practice [DDD].

Some requirements are functional, others are non-functional.

Functional requirements describe what the system must do: a night vision device must be able to represent heat radiation as a video stream; a multiplayer game must create a shared virtual world for users to interact with over a network; a tool for formatting floppies … er, formats floppies.

Non-functional requirements, also known as forces, define expected properties of the system and are known to drive architectural decisions [POSA1, POSA5]. They may be formulated or implied: our game should be fast enough and stable enough. A medical application should be extremely well-tested. An online shop should provide an easy way to add new goods. Notice all those “fast enough”, “stable enough”, “well”, and “easy” terms on the wishlist. Sometimes they form an SLA with numbers: your service should be available 99.999% of the time.

Let’s take an example.

A night vision surveillance camera may spend seconds compressing its video stream to limit the required network bandwidth – this kind of system sacrifices low latency in favor of low traffic. The device will need a fast CPU (probably a DSP) and lots of RAM to store multiple frames for efficient compression.

A night vision camera of a drone should have moderately low latency as the drone (and probably its operator) uses the video stream for navigation. Thus it should send out every frame immediately, except that it may still spend some time compressing the frame to JPEG to achieve a balance between latency and bandwidth. Pushing for extremely low latency of the camera does not help much because the whole system is limited by the delay of the radio communication and the human operator in the loop.

Night vision goggles or helmets are stringent on latency to the extent which no ordinary digital system satisfies, thus expensive analog devices have to be used.

Here we see how non-functional requirements – namely, latency, bandwidth and cost – impact all the stuff all the way down to hardware. The same happens with multiplayer games: while a chess client is a simple web page, a fighting tournament or a first-person shooter is very likely to need a client-installed application that processes much of the game logic locally while relying on a highly customized network protocol to decrease communication latency.

Another example is the choice of programming language: you can quickly write your system in Java or Python sacrificing its performance or you can spend much more time with C or C++ and manual optimization to achieve top performance at the cost of development speed.

Conflicting forces #

We see that forces influence architecture. That becomes way more interesting when a system is shaped by conflicting forces – the ones that, though opposing each other, still need to be met by the architecture.

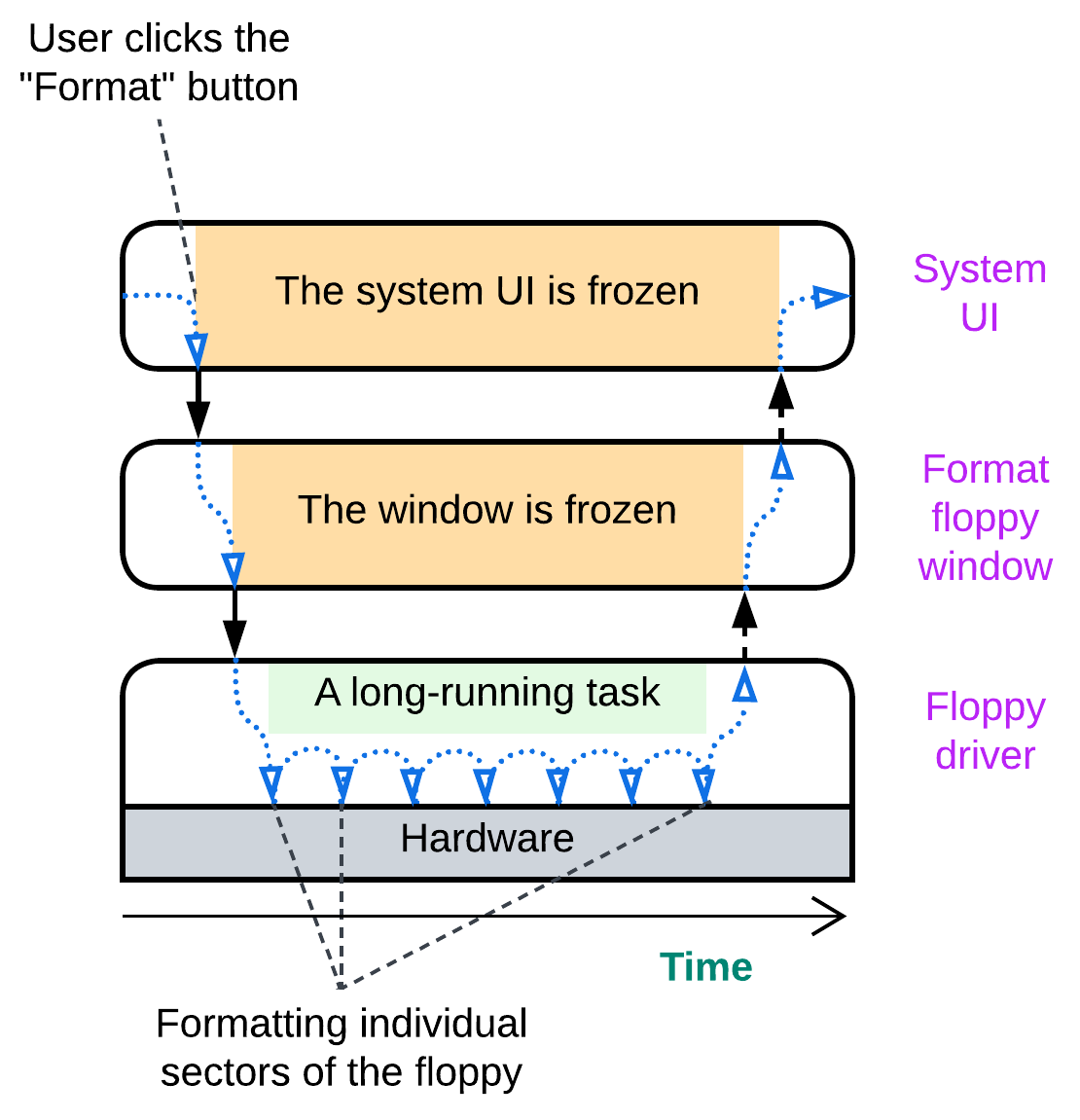

Remember how old Windows used to freeze on formatting a floppy or when it encountered one with a bad cluster? Let’s see how such things could have happened (though the real cause was a bit different, it also came from the modules’ sharing a context).

The system implements the function it was made for – it formats floppies. However, while the low-level module is busy interacting with the hardware, all the modules above it have no chance to run because they have called the driver and are waiting for it to return. The modules are there, with the code separated into bounded contexts (the UI does not need to care about sectors and FATs) but all of them share non-functional properties – latency in this case. Either the UI is responsive or the floppy driver runs a long-running action. We need the UI and the driver to execute independently.

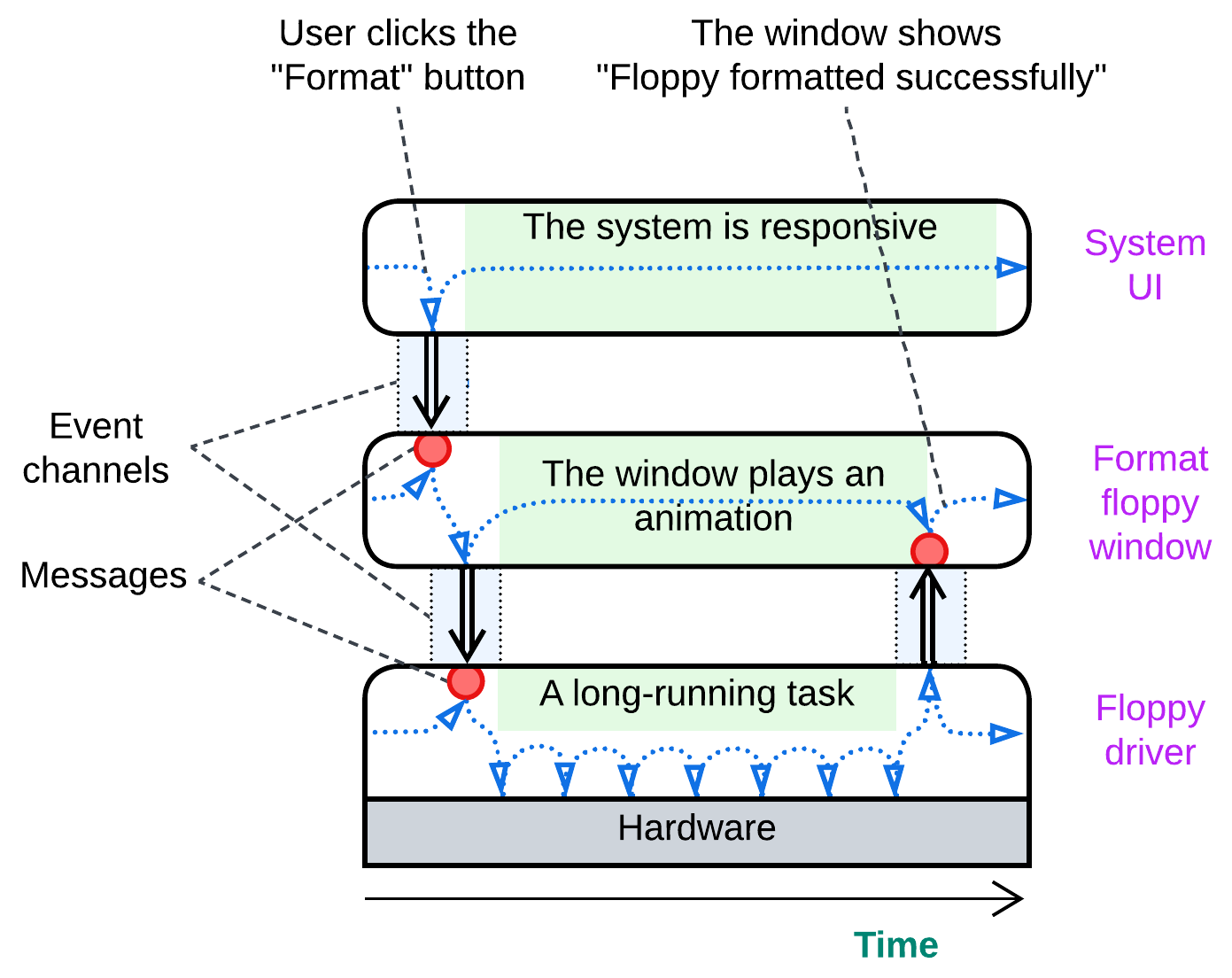

Asynchronous communication #

If the modules cannot communicate directly (call each other and wait for the results returned) how should they interact? Through an intermediary where one of the modules leaves a message for another. Such an intermediary may be a message queue, a pub/sub channel, or even a data record in shared memory. The sender posts its message and continues its routine tasks. The receiver checks for incoming messages whenever it has a free time slot. Behold multithreading in action!

Distribution #

Once modules run independently, we can separate them into processes and even distribute the processes over multiple computers. That is required to address fault tolerance and high availability and solve conflicts around scaling or locality.

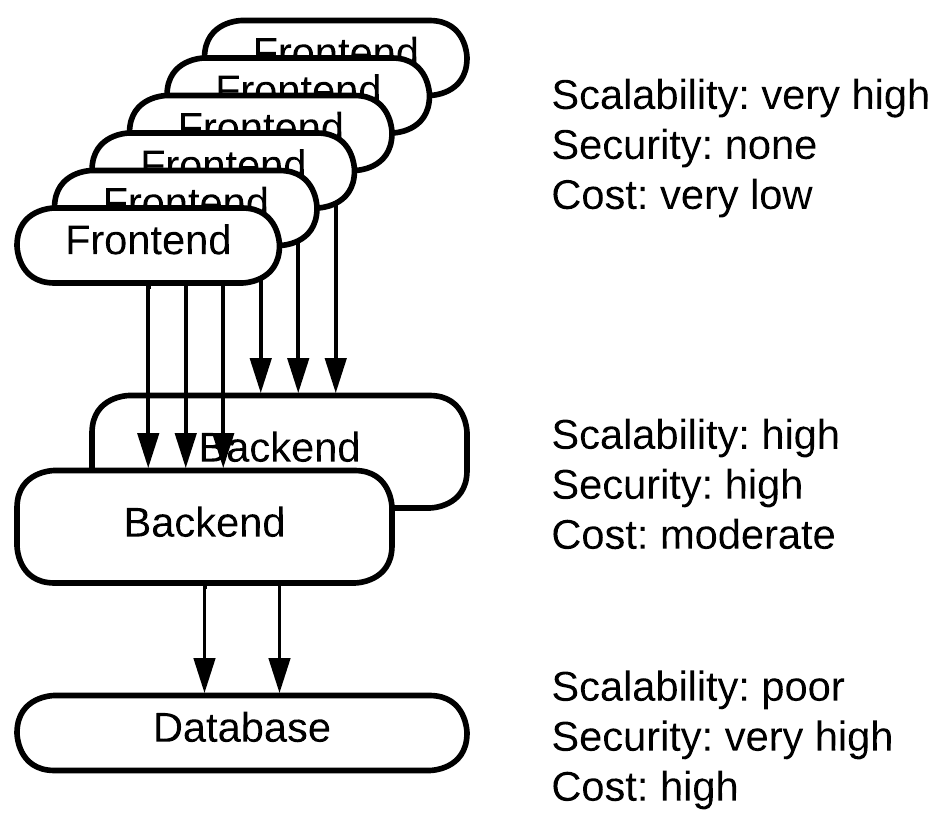

Consider a web site. Most of them follow Three-Tier Architecture:

- A frontend runs in users’ browsers.

- A backend runs on the business owner’s servers.

- A database usually runs on a single powerful server.

This common division makes quite a lot of sense:

Websites are accessed by many users simultaneously. Any business owner wants to pay less for his servers, thus as much work as possible is offloaded to the users’ web browsers which provide unlimited resources for free (from the business owner’s viewpoint). Here we have a nearly perfect scalability – the business owner pays only for the traffic.

Other parts of the software are business-critical and should be protected from hacking. Such ones are kept on private servers or in a cloud. This means that the business owner pays for the servers while they may scale their application by flooding it with money.

The deepest layer – the database – is nontrivial to scale. Distributed databases are expensive, consume a lot of traffic, and still scale only to a limited extent. It often makes more sense to buy or rent top-tier hardware for a single database server than to switch over to a distributed database.

This is a good example of how the physical distribution of a system solves the scalability, security, and cost conflict by choosing the best possible combination of forces for each module. Whatever is not secure scales for free. Whatever does not scale gets assigned expensive hardware. Whatever remains is in between.

Another example comes from IoT – a fire alarm system. They tend to use 3 tiers as well:

- Sensors (smoke or fire detectors) and actuators (fire suppression, sirens, etc.).

- A field gateway – a kind of router the sensors and actuators are directly connected to.

- A control panel – some place where operators drink their coffee.

Sensors and actuators are cheap and energy-efficient but dumb devices. They do not react to events unless explicitly commanded. The control panel is where all the magic happens, but it may be unreachable if the network is damaged or the wireless communication is jammed. Field gateways stand in between: they collect information from the sensors, aggregate it to save on traffic, communicate with the control panel, and even activate actuators if the control panel is unreachable. In this case a part of the business logic is installed in the dedicated devices which are located within the controlled building.

Here reliability conflicts with accuracy: a human operator makes an accurate estimate of the threat and chooses an appropriate action, but it is not granted that we can always reach the operator. Thus to be reliable we add an inaccurate but trustworthy fallback reaction.

A similar pattern can be found with robotics, drones or even computer hardware (e.g. a HDD): dedicated peripheral controllers supervise their managed devices in real time while a more powerful but less interactive central processor drives the system as a whole.

The goods and the price #

Let’s review what we found out.

Modules make it easier to reason about the system, enable development by multiple teams in parallel, and resolve some conflicts between forces. For example, development speed against performance or release frequency against stability are solved by choosing a programming language and release management style on a per module basis.

The cost is the loss of some options for performance optimization between modules and the extra cognitive load while debugging a module you are not familiar with.

Asynchronous communication is a step forward from modules that solves more conflicts between forces. It addresses latency and multitasking.

We pay for that with context switches and the need to copy and serialize data transferred in messages, making communication between participating modules slower. Debugging asynchronous communication becomes non-trivial as one cannot single-step in the debugger from the message sender into the message handler.

Distribution builds on asynchronous communication (as networks are asynchronous) and decouples participant components in such forces as scalability, security and locality. It separates release cycles of the services involved and makes it possible for the system to recover from failures of some of its components.

The price? Even slower and more complicated communication in the now distributed system (networks are quite laggy and unreliable) and extremely inconvenient debugging as you need to connect to multiple components over the network.

We see that the more isolated our modules become, the more forces are decoupled and the more flexible the resulting system grows. But this very same decoupling devastates the system’s performance and makes debugging into a nightmare.

Any moral? There is one, even a few.

- Do not overisolate. Go asynchronous or distributed only if you are forced to. Especially if you are actively evolving your system. Especially in an unfamiliar domain.

- Cohesive logic belongs together. If you split it among asynchronous or distributed components, it may become very hard to debug.

- Components that communicate a lot should reside together. Distributing them may kill performance and even break the consistency of the data.