Shared data #

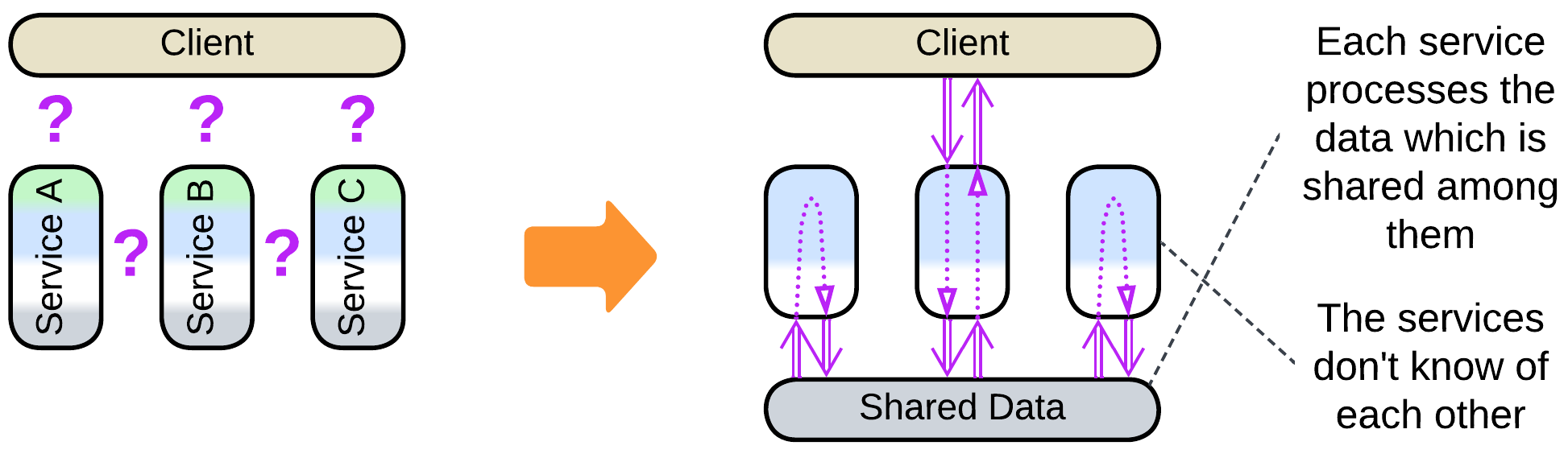

The final approach is integration through shared data (Shared Repository):

The shared data is a “blackboard” available for each service to read from and write to. It is passive (as controlled by the services) and does not contain any logic except for the data schema, which represents a part of the domain knowledge. That makes communication through shared data the antipode of orchestration, which also features a shared component, Orchestrator, which is, however, active (controls services) and contains business logic, not data.

Shared data can be used for storage, messaging, or both:

Storage #

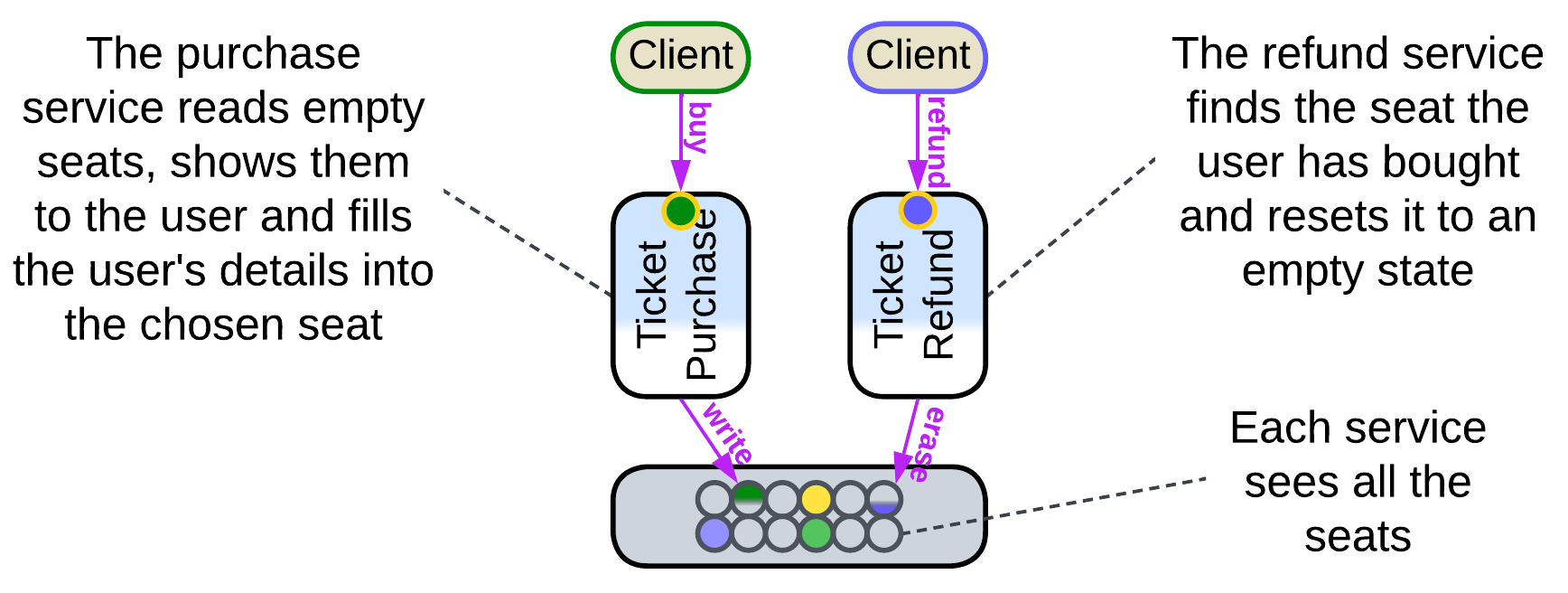

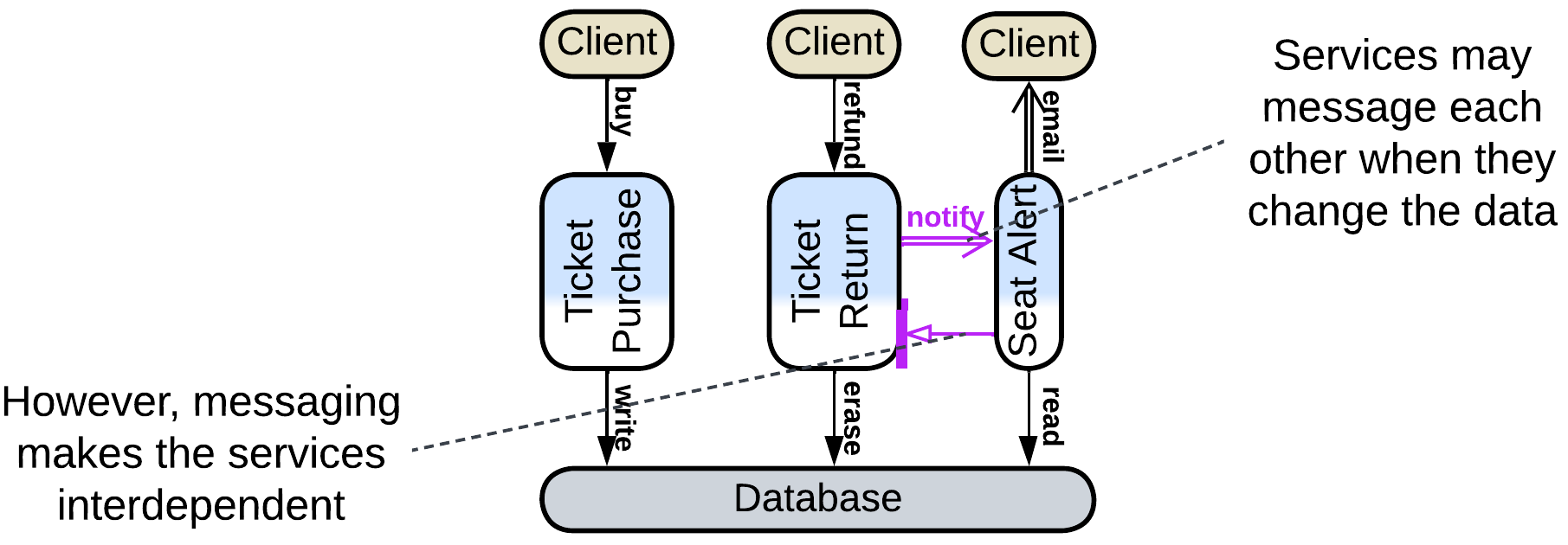

The most common case of shared data is storage (usually a database, sometimes a file system) for a (sub)domain that has functionally independent services which operate on a common dataset. For example, a ticket purchase service and a ticket refund service share a database of ticket details. The ticket purchase service reads in the available seats and fills in ticket data for purchases. The ticket refund service should be able to find all tickets bought by a user and delete the user data from seats refunded. The only communication between the purchase and refund services is the shared database of tickets or seats, so that one of them sees the changes made by the other the next time it reads the data.

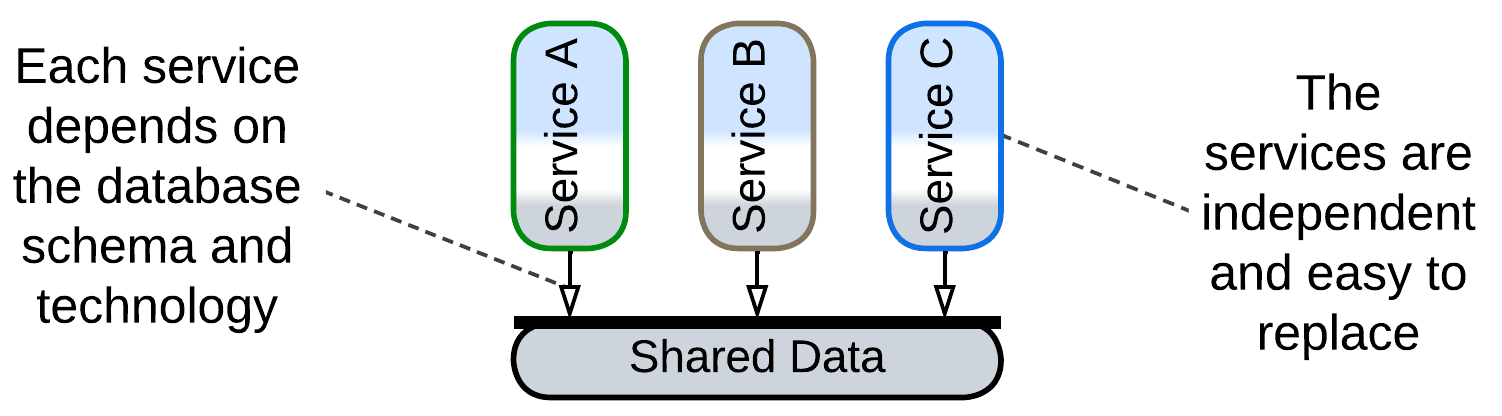

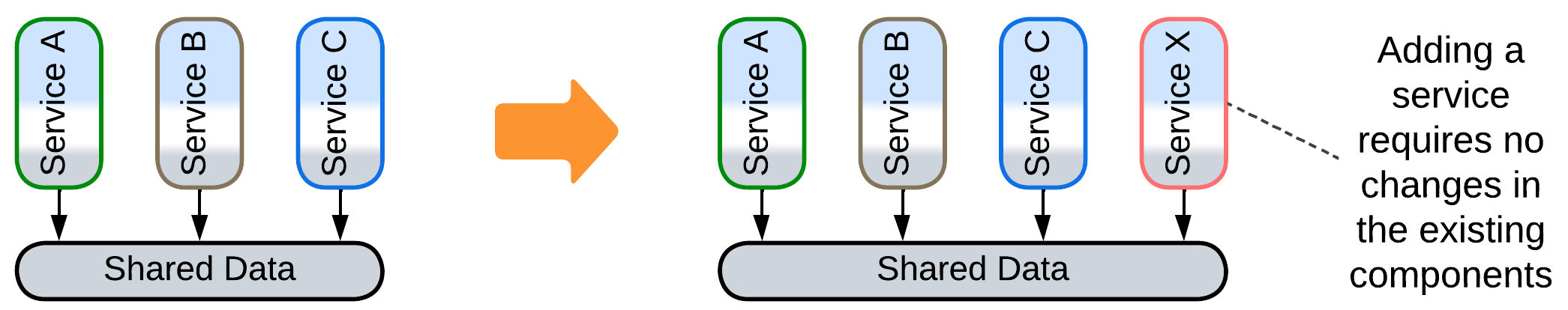

With this model the services don’t depend on each other – instead, they depend on the shared (domain) data format and the database technology. Thus, it is easy to add, modify, or remove services but hard to change the shared data structure or, especially, the database vendor.

Services usually need to coordinate their actions. Commonly, services with a shared database rely on a messaging Middleware for communication. Users of our ticketing system will want to be notified (through email, SMS or an instant message) when a free seat that they are interested in appears. We’re not going to complicate either of the existing services by integration with instant messengers, so we will create a new notification service, which must track each returned ticket to see if any user wants to buy it. This is easily implemented by the return service publishing and the notification service subscribing to a ticket return event, mixing in a bit of choreography into our data-centric backend.

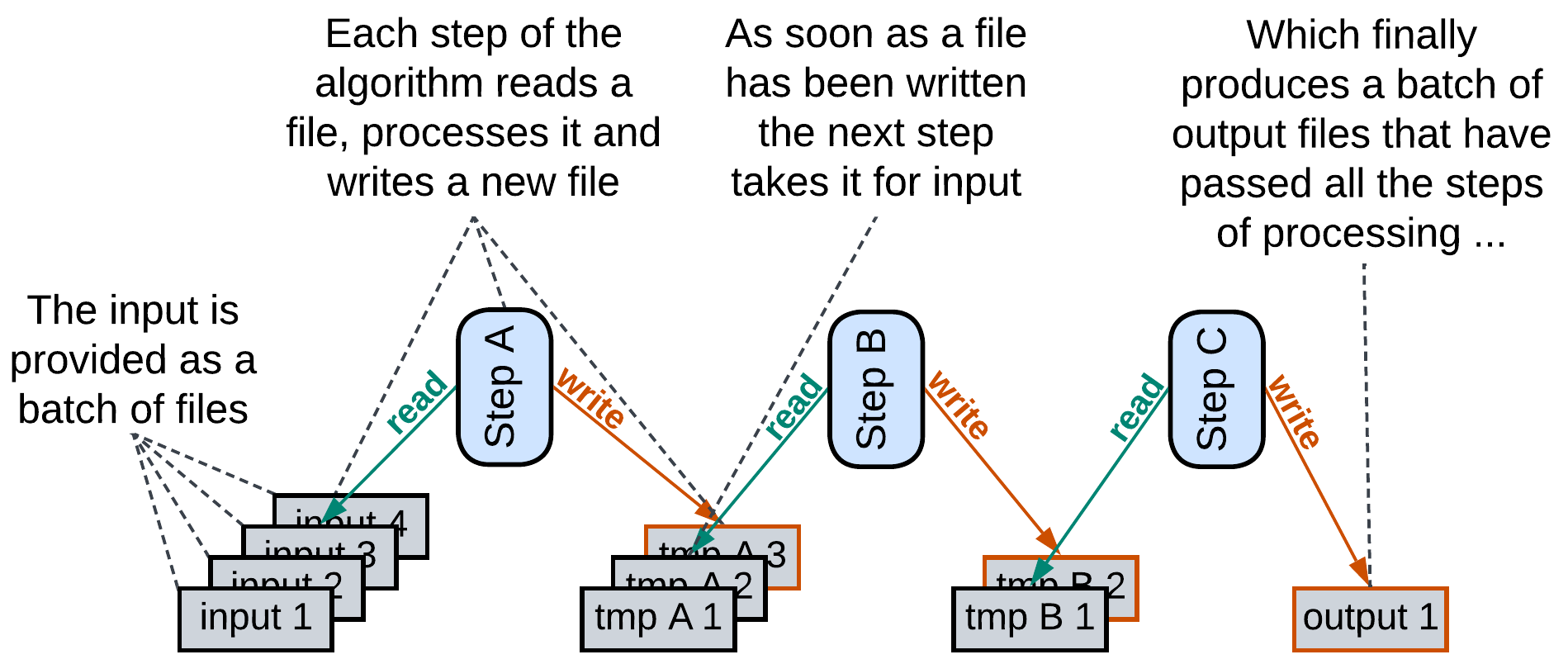

Another case is found with data processing pipelines where an element may periodically read new files from a folder or new records from a database table to avoid implementing notifications. This increases latency and may cause a little CPU load when the system is idle, but is perfectly ok for long-running calculations.

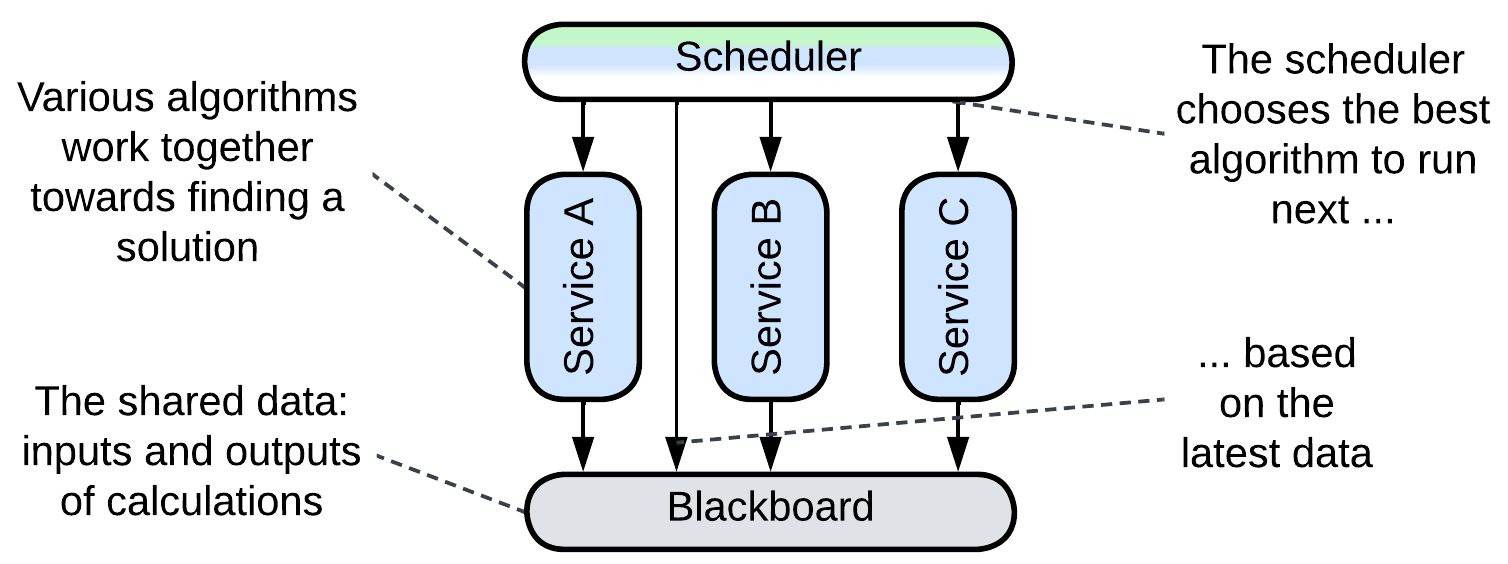

Finally, there is the rarely used option of an external Scheduler which selects the services which should run based on the data available. This is known as the Blackboard pattern and something similar happens in 3D game engines. The Scheduler (which is an Orchestrator, by the way) is needed when CPU (or GPU or RAM) resources are much lower than what the services would consume if all of them ran in parallel, thus they must be given priorities, and the priorities change based on the context which is regularly estimated from the system’s data.

Messaging #

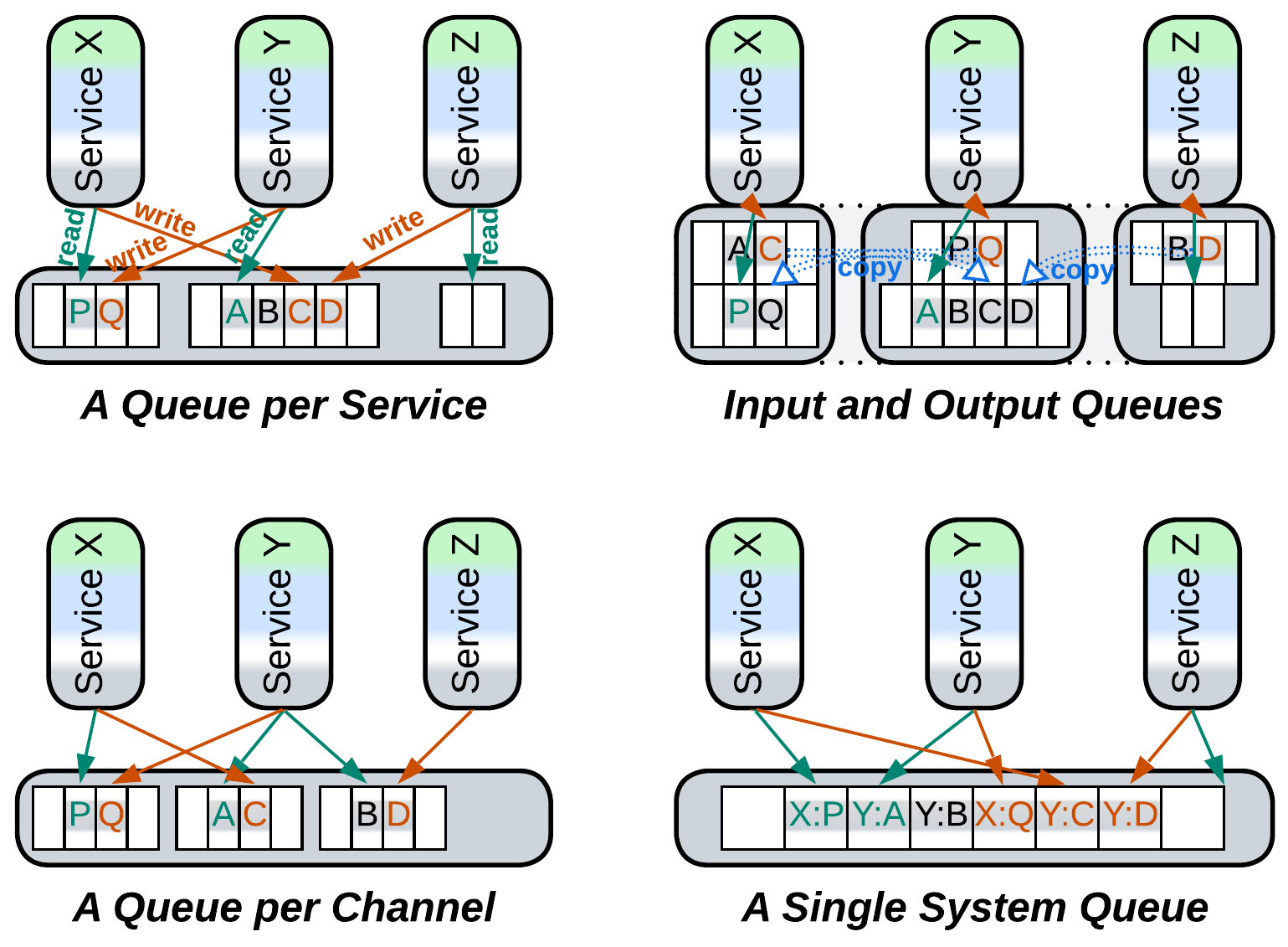

The other, not as obvious, use case for shared data is messaging, which is implemented by the sender writing to a (shared) queue (or log) while the recipient is waiting to read from it. Queues can be used for any kind of messages: request/confirm pairs, commands, or notifications. Each service may have a dedicated queue (either input for commands mode or output for notifications), a pair of queues (messages from the service’s output are duplicated by an underlying distributed Middleware to input queues of their destinations), or there may be a queue per communication channel, or a single queue for the entire system (or a global queue per message priority) with each message carrying destination id (for commands) or topic (for notifications).

The use of shared data for messaging turns our datastore into a Middleware. The dependencies are identical to those in choreography – each service depends on the APIs of its destinations for commands or its sources for notifications.

There should be a means for the recipient of a message to know about its arrival so that it starts processing the input. Usually a messaging Middleware implements a receive() method for the service to block on. However, very low latency applications, like HFT, may busy-wait by repeatedly re-reading the shared memory so that the service starts processing the incoming data immediately on its arrival, bypassing the OS scheduler. This is the fastest means of communication available in software.

Full-featured #

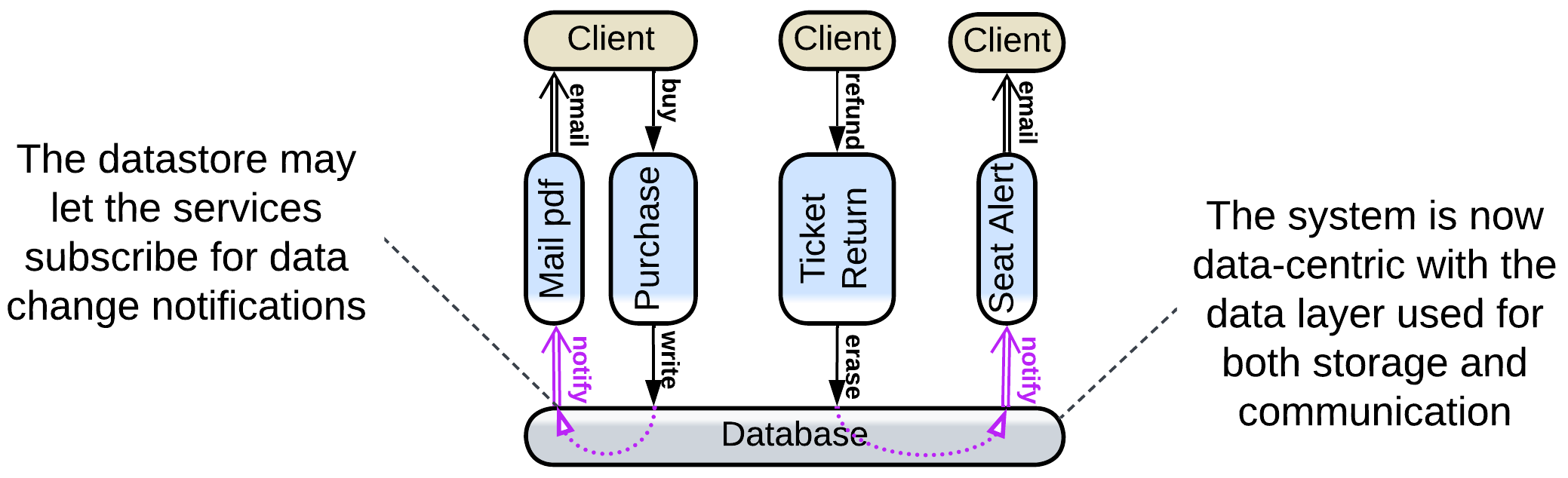

Finally, some (usually distributed) datastores implement data change notifications. That allows for the services to communicate through the datastore in real-time, removing both the need for an additional Middleware and interdependencies for the services. Such a system follows the Shared Repository pattern of [POSA4] which was rectified as Space-Based Architecture [SAP, FSA]. In our example, the available seats notification service subscribes to changes in the seats data in the database – this way it does not need to be aware of the existence of other services at all. We can also move the email notifications logic of the ticket purchase service into a separate component which would track purchases in the database and send a printable version of each newly acquired ticket to the buyer’s email address which can be found in the ticket details in the database.

Summary #

Communication through shared data is best suited for data-centric domains (for example, ticket purchase). It allows for the services to be unaware of each other’s existence, just as they are with orchestration, but the structure of the domain data becomes hard to change as it is referenced all over the code. Shared data may also be used to implement messaging.