Orchestration #

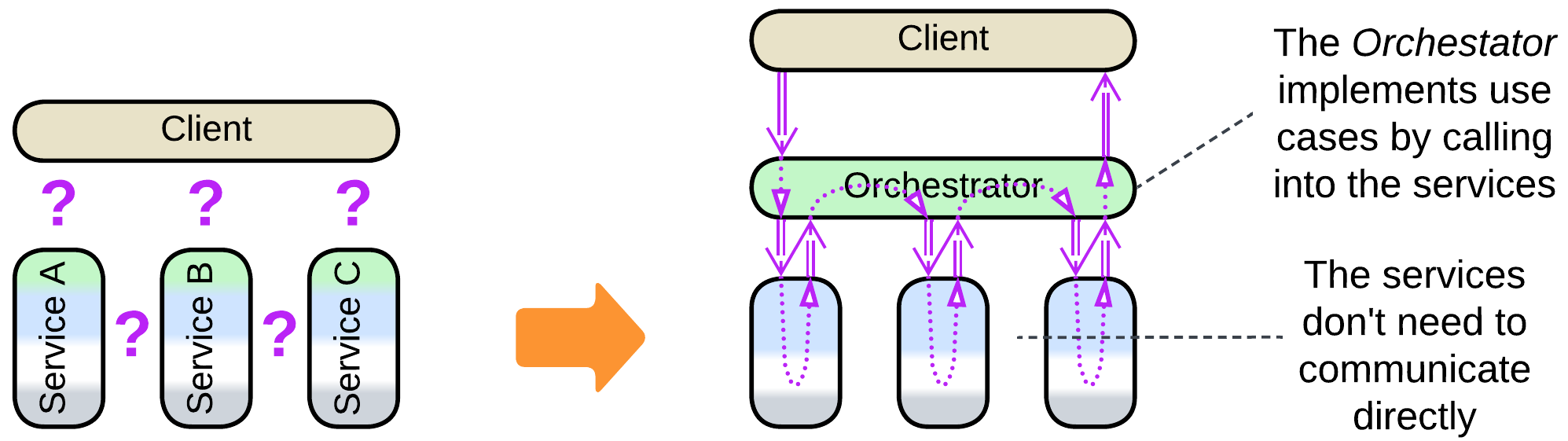

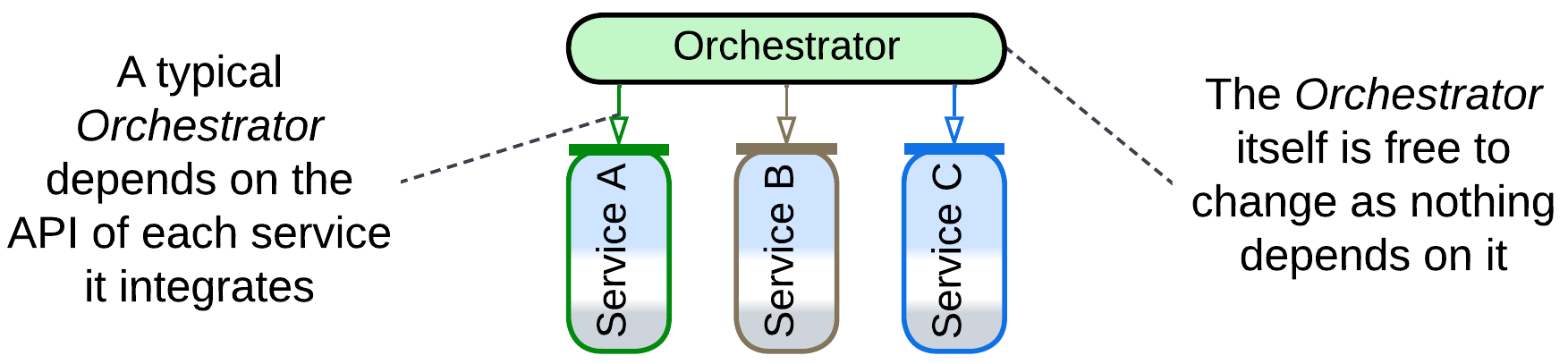

The most straightforward way to integrate services is to add a coordinating layer (Orchestrator) on top of them:

The good thing is that your Orchestrator has explicit code for every use case it covers and every running scenario gets an associated thread, coroutine, or object so that you are able to attach to the Orchestrator and debug any use case step by step. Nor do you have to worry about keeping the state of the services consistent as they are passive with all the changes in the system being driven by the Orchestrator.

Orchestration is the default approach for single-process (desktop) applications where it is faster to call into an orchestrated module and return than to send it a message. However, in distributed systems orchestration doubles the communication overhead (when compared to choreography or shared data) as every method call into an orchestrated service uses two messages: request and confirmation.

Roles #

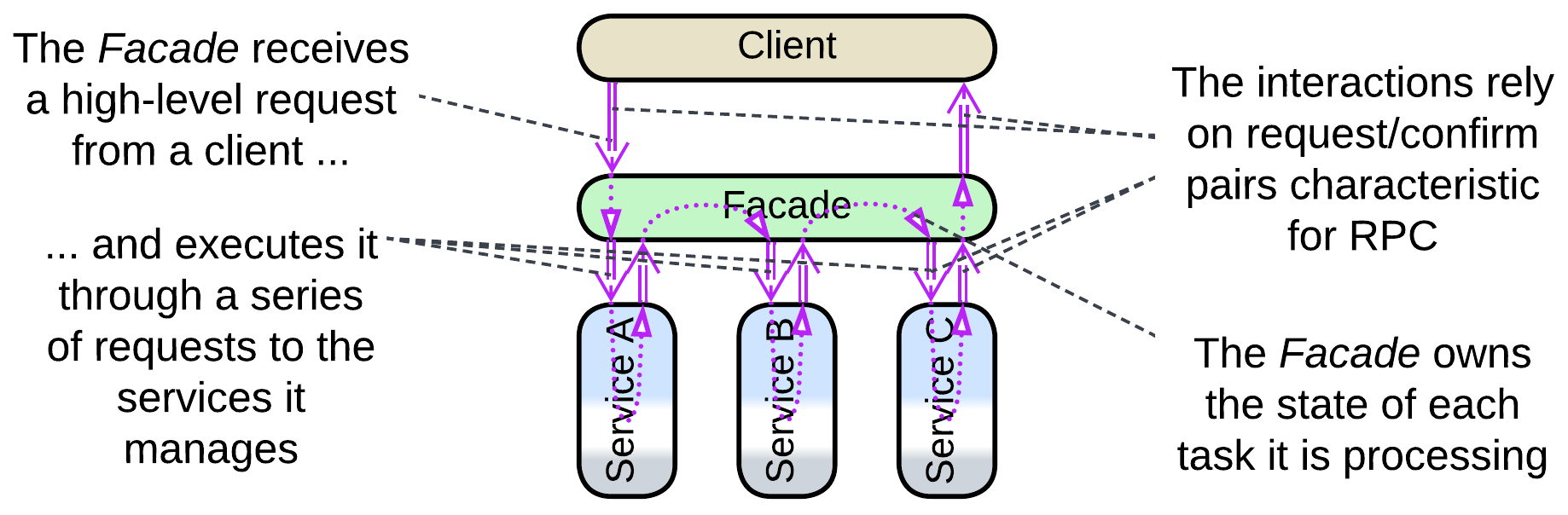

In a backend which serves client requests an Orchestrator takes the role of Facade [GoF] – a module that provides and implements a high-level interface for a multicomponent system. It sends requests to the underlying services and waits for their confirmations – the mode of action that can be wrapped in an RPC (remote procedure call). The state of each scenario that the facade runs resides in the associated thread’s or coroutine’s call stack (for Reactor [POSA2] or Half-Sync/Half-Async [POSA2] implementations, correspondingly) or in a dedicated object (for Proactor [POSA2]).

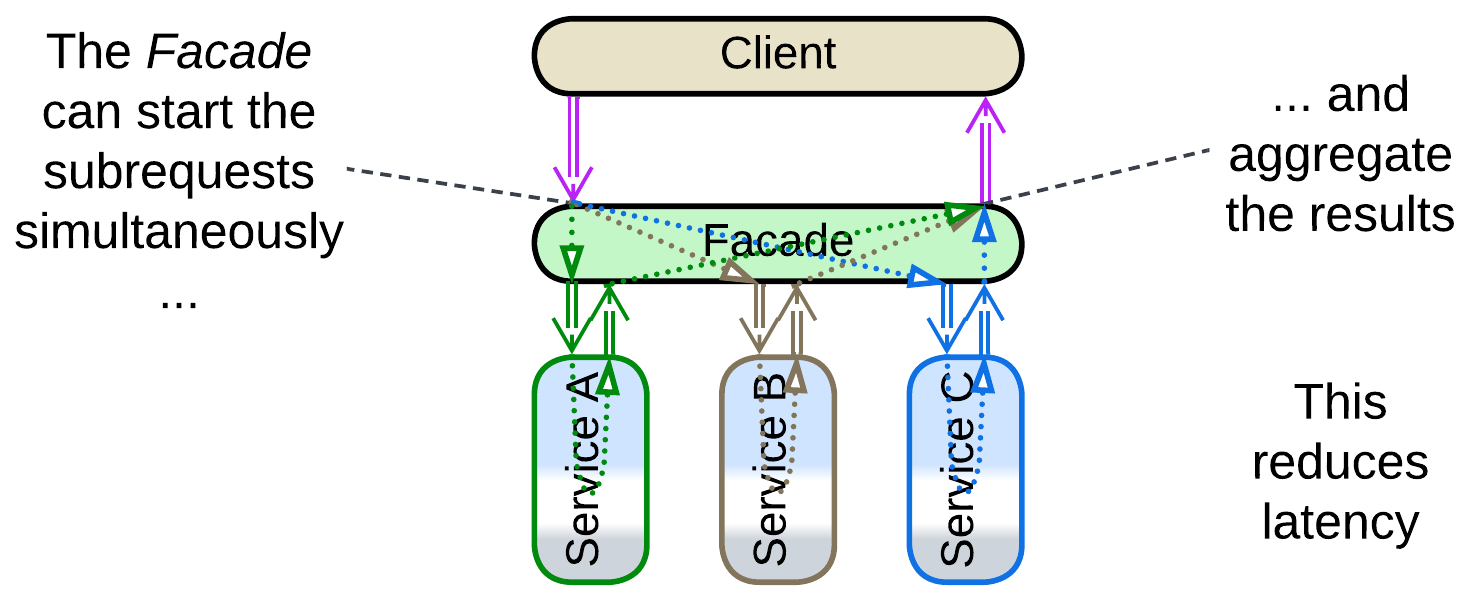

A Facade also supports querying the services in parallel and collecting the data returned into a single message through the Splitter and Aggregator patterns of [EIP]. That reduces latency (and resource consumption as the whole task is completed faster) for scatter or gather requests when compared to sequential execution.

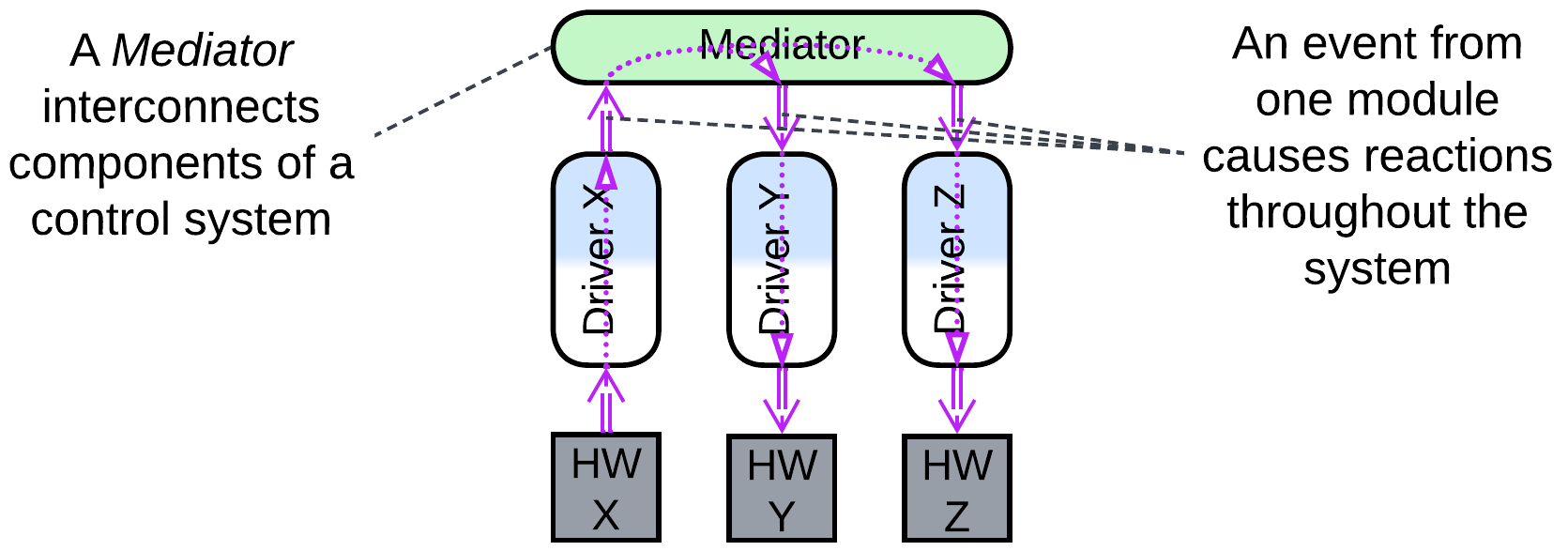

Embedded and system programming – the areas that deal with automating control of hardware or distributed software – employ Orchestrators as Mediators [GoF] – components that keep the state of the whole system (and, by implication, any hardware it may manage) consistent by enacting a system-wide reaction to any observable change in any of the system’s constituents. A mediator operates in non-blocking, fire-and-forget mode which is more characteristic of choreography, to be discussed below. This also means that you will not be able to debug a use case as a thread – because there are no predefined scenarios in control software!

Such a difference may be rooted in the direction of the control and information flow: in a backend it comes as a high-level command while control systems react to low-level events.

Dependencies #

By default an Orchestrator depends on each service which it manages – that means that a change in a service’s interface or contract – caused by fixing a bug, adding a feature, or optimizing performance – requires corresponding changes in the Orchestrator. That is acceptable as the Orchestrator’s client-facing, high-level logic tends to evolve much faster than the business rules of the lower layer of services, therefore the team behind the orchestrator, unrestricted by other components depending on it, will likely release way more often than any other team. However, as the number of the managed services and the lengths of their APIs increase, so does the amount of information that the Orchestrator’s team must remember and the influx of changes they must integrate in their code. For a large project the workload of supporting the orchestration layer may paralyze its development – that was a major reason behind the decline of Enterprise SOA [FSA] where ESB used to orchestrate all the interactions in the system, including those between domain-level services and components of the utility layer.

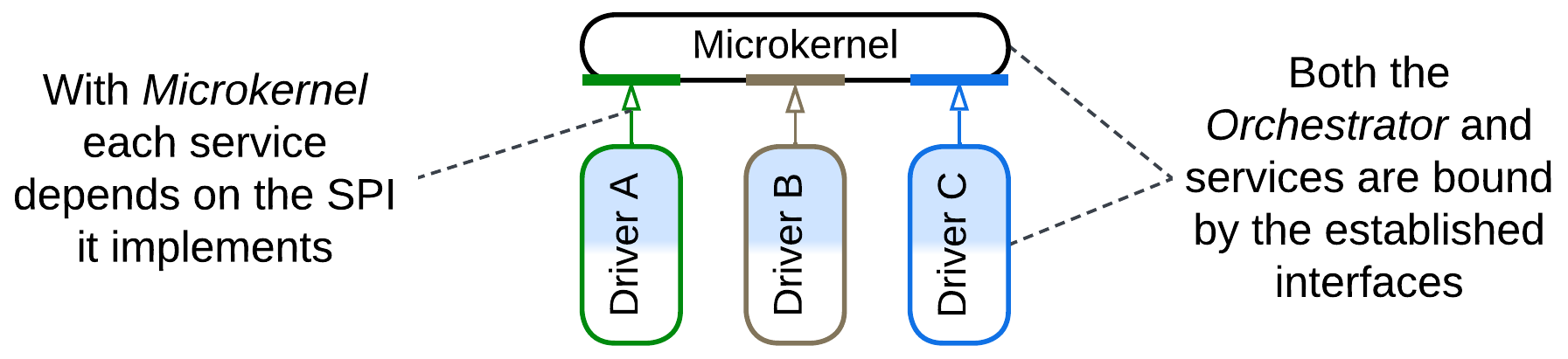

Another option, which appears in Plugins and develops in Microkernel and Hexagonal Architecture stems from dependency inversion: the Orchestrator defines an SPI (service provider interface) for every service. That makes each service depend on the Orchestrator so that a single Orchestrator’s team does not need to follow updates of the multiple services’ APIs – instead it initiates the changes at its own pace. However, with that approach the design of an SPI requires coordination from the teams on both sides of it and the once settled interface becomes hard to change. The most famous example of modules that implement SPIs are OS drivers.

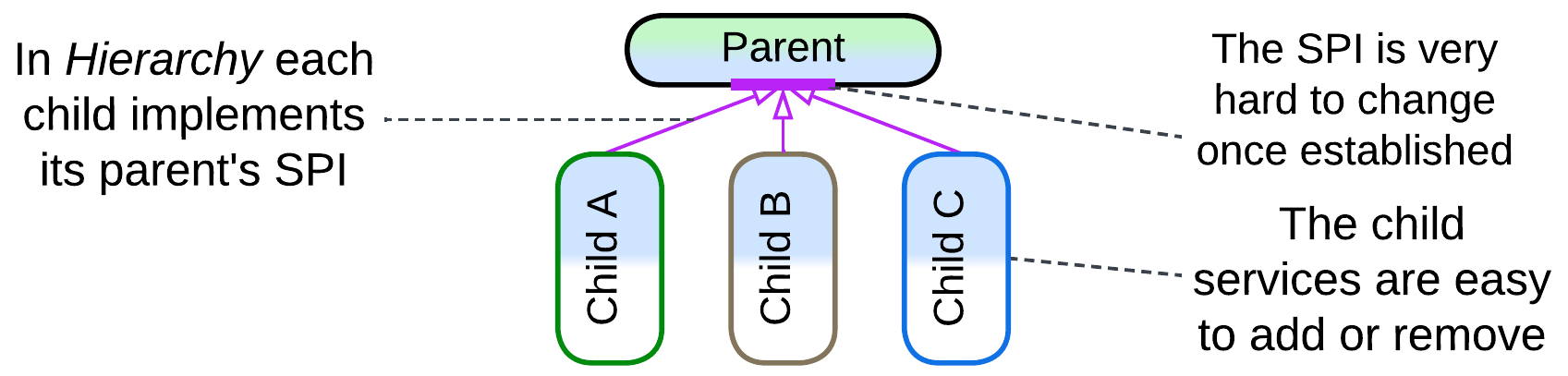

Furthermore, some domains develop that idea into a Hierarchy: when services implement related concepts, they may match a single SPI, making the Orchestrator simpler (as there is no more need to remember multiple interfaces). That is the case with telecom or payment gateways and it may also be found with trees of product categories in online marketplaces.

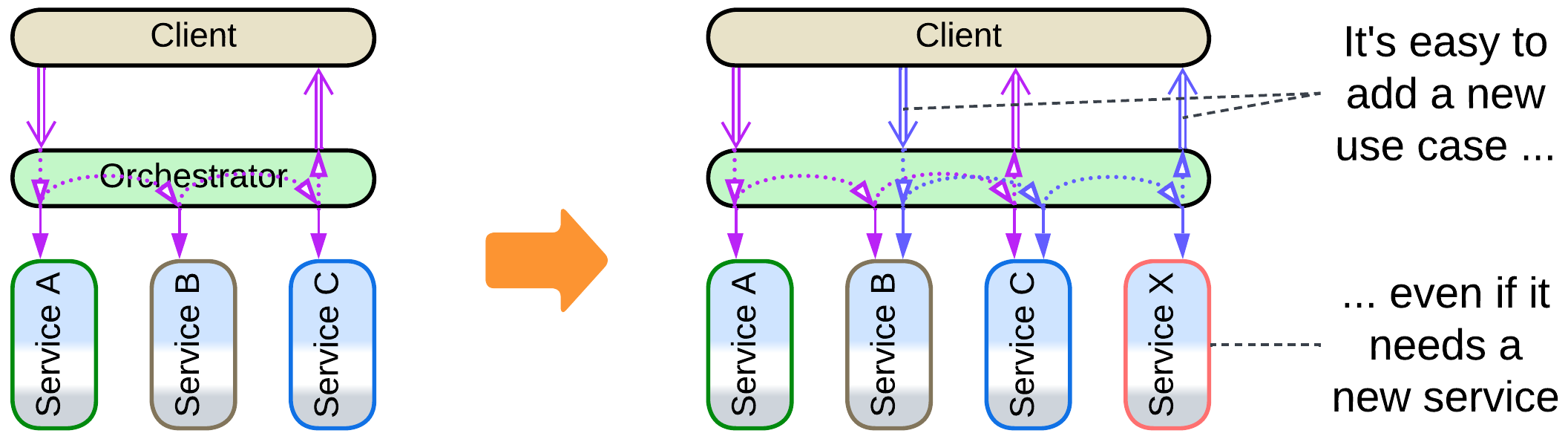

All kinds of orchestration allow for an easy addition of new use cases which may even involve new services as that changes nothing in the existing code. However, removing or restructuring (splitting or merging) previously integrated services requires much work within the orchestrator, except for in a Hierarchy where all the services implement the same interface which means that the code in the Orchestrator does not depend (much) on any specific child.

Mutual orchestration #

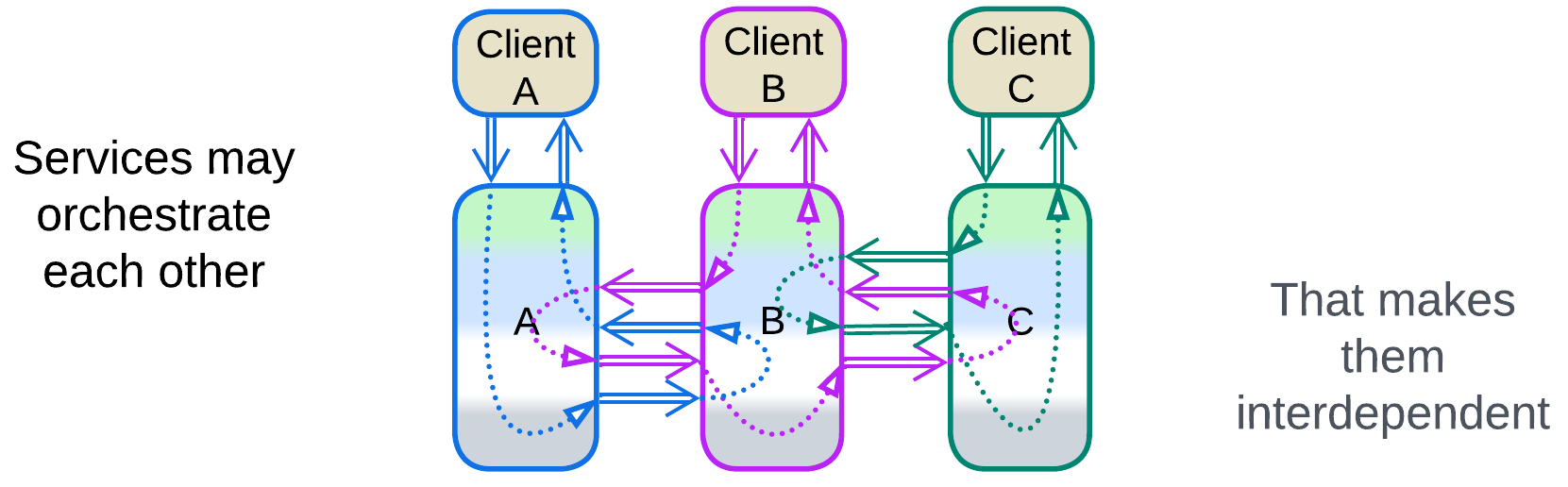

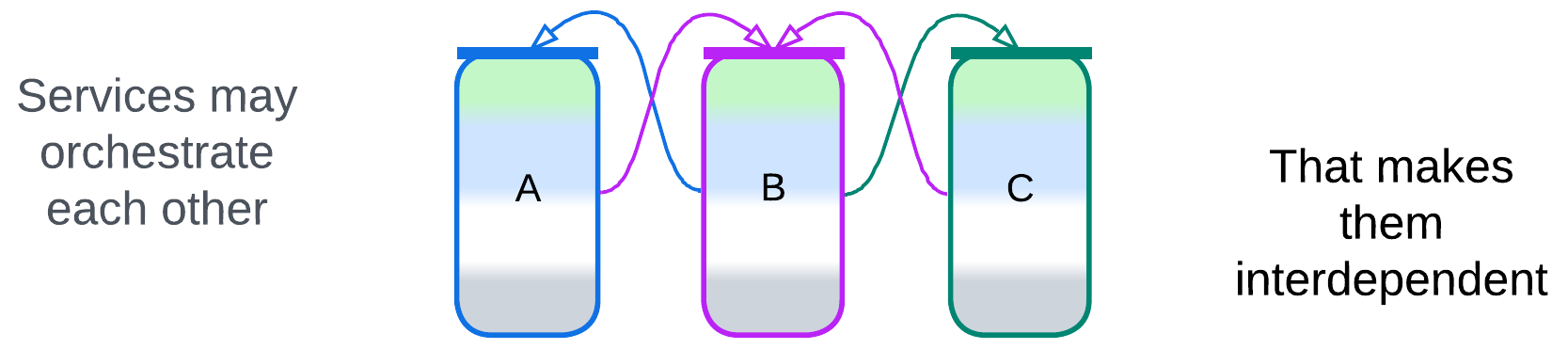

In some systems there are several services that have their own kinds of clients (for example, employees of different departments). Each of the services tries hard to process its clients’ requests on its own but occasionally still needs help from other parts of the system. This creates a paradoxical case where several services orchestrate each other:

As each of the services depends on the APIs of the others, any change to any interface or composition of such a system requires consent and collaboration from every team as it impacts the code of all the services.

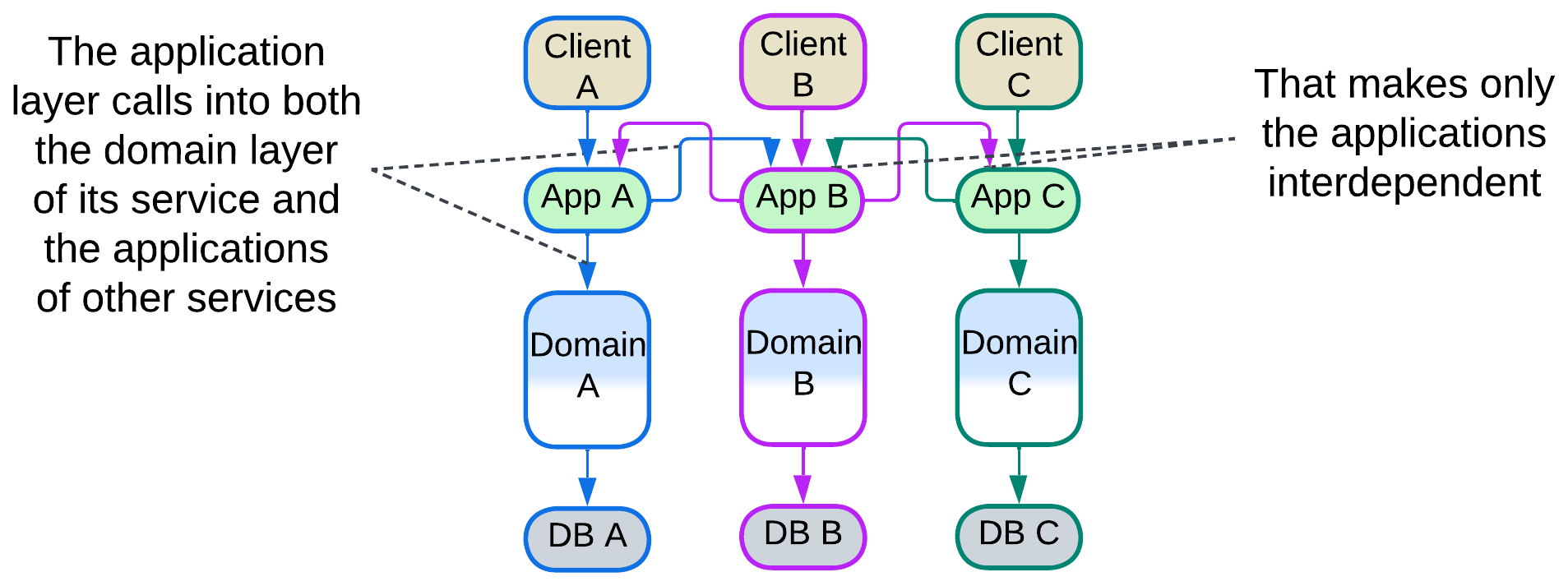

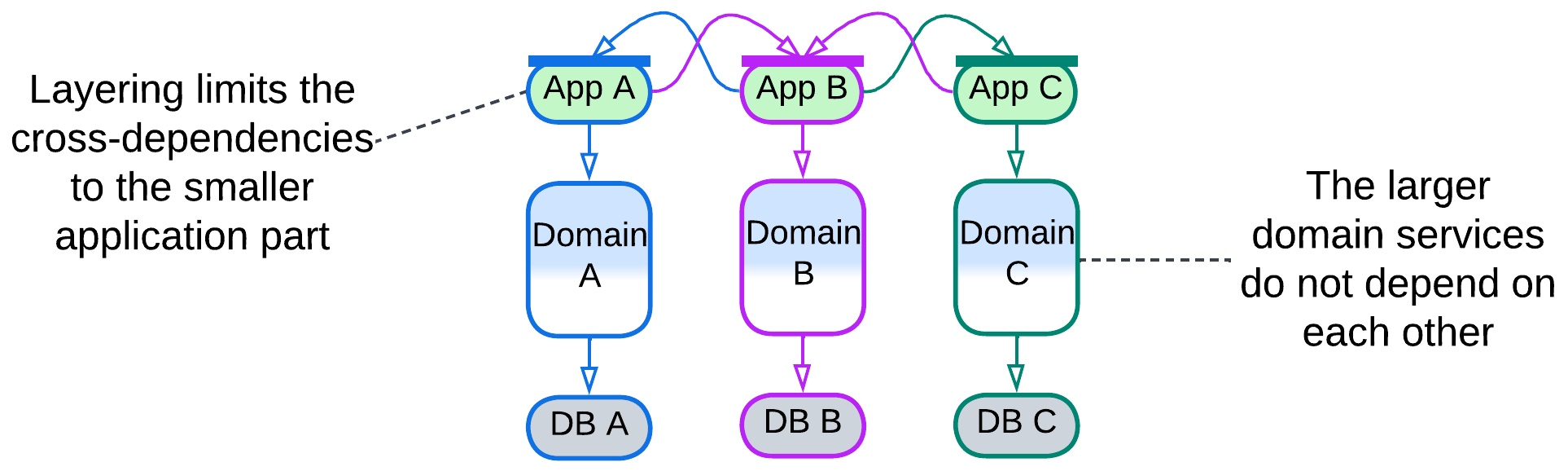

In real life services are likely to be layered, with their upper layers acting as both internal and external Orchestrators. Layering isolates interdependencies to the relatively small application-level components and resolves, to an extent, the seemingly counterintuitive case of mutual orchestration as now there is an explicit, though fragmented, system-wide orchestration layer.

Summary #

Orchestration represents use cases as a code, allowing for an orchestrated system to support many complex scenarios. Dealing with errors is as trivial as properly handling exceptions. This approach trades performance for clarity.