Choreography #

Another integration option is to build a Pipeline to pass every client’s request through a chain of components:

In that case there is no owner for workflows – each request is just a data packet which is transformed multiple times as it passes through the Pipeline. Debugging is mostly limited to reading logs as there is no dedicated component to connect to for single-step execution of a use case. Nor is there a single piece of code to define each of the system-wide scenarios – their logic emerges from the graph of event channels that connect services and from messages that each involved event handler sends. Consistency of the services’ states is the responsibility of the services themselves as there is none supervising them.

On the bright side, there is no communication overhead caused by response messages as there are no responses – the processing cost is one message per service, half of the cost for an orchestrated architecture. Still, messages in choreographed systems tend to be longer than those used with orchestration as each message needs to carry the entire request’s state – there is no Orchestrator to own the state and distribute parts of the payload among involved services.

Latency may also be suboptimal as parallelizing execution of a request is easier said than done because there is no place (Aggregator [EIP]) to collect multiple related messages, which also means that there is no associated cost in resources (RAM and CPU time) for storing their fragments. Please note that an Aggregator, when added, starts orchestrating the system – it stands between the client and services and meddles with the traffic and logic. It spends resources to store the received messages for aggregation, and the messages start forming request/confirm pairs – which are characteristic of orchestration.

Still another trouble with choreography comes from its weakness in error processing. When a service in the middle of a request processing pipeline encounters an error, it cannot generate its normal output to be sent further downstream. One option is to fill in a null (or error) value but then each receiver of the message should remember to check for null and know how to deal with an error. Another way is adding a dedicated error channel for each service to push failed requests into, but that complicates the whole system’s structure. Moreover, a failure in the middle of processing a request may cause the services to end up with inconsistent data if no special attention (a new kind of request to compensate the original one) is paid to roll back the partial change. Please note that all of that is conveniently handled by an Orchestrator.

Early response #

The ordinary mode of action for a pipeline – sending the final results of processing to the client – requires either for the tail of the pipeline to send data to its head or for existence of a stateful intermediate component – Gateway – to receive the client’s request, forward it to the head of the pipeline, wait on the pipeline’s tail for the result of processing, and return it to the client. That is necessary because a client would usually open a single connection which is impossible to share between multiple services, namely the (receiving) head and (sending) tail of the pipeline.

The gateway, if used, may parallelize processing of scatter or gather requests by turning into an API Gateway which is a kind of Orchestrator. Which means that the system changes its paradigm from choreography to orchestration.

It is possible to avoid both adding a Gateway and having the cyclic dependency if clients don’t immediately need the final results of processing their requests. In such a case the service which receives the original request does its (first) step of processing, sends the response to the client, and then notifies services down the pipeline. Though such a use case seems to be unlikely, it happens in real life, for example, with pizza delivery. As soon as a buyer fills in their contact details and pays for the food, the order can be confirmed and forwarded to the kitchen. When it is ready it’s forwarded to the delivery, and finally the physical goods appear at the buyer’s door.

Early response allows for choreography to shine in its purest form: with extensibility, high performance, but also high latency. A similar approach may be used in Service-Based Architecture [FSA] (aka Macroservices) for communication between the services (bounded contexts) if they only need to notify each other of events without waiting for responses.

Dependencies #

A pipeline may be built with downstream or upstream dependencies or with a shared schema.

If services communicate through commands, each service depends on all the direct destinations of its commands as it must know each of the APIs which it uses. This mode of communication is mostly used with Actors that power embedded, telecom, messengers, and some banking systems. Downstream dependencies make it easy to add input chains (upstream services that deal with new hardware or external components) although changing anything at the output end of the pipeline is going to break the input parts that send messages to the component changed.

Upstream dependencies come from the publish/subscribe model where each service broadcasts notifications about what it has done to any interested subscriber. This way of building systems engines Event-Driven Architecture [FSA] which is used in high-load backends. Extending or truncating an already implemented request processing tree is as easy as adding or removing subscribers to existing events but the creation of a new event source will require changes in the downstream components. The easy addition of downstream branches supports new customer experiences and analytical features which business is hungry for.

The final option is for the entire pipeline to use a uniform message format (Stamp Coupling [SAHP]) which often contains one dedicated field per service involved. This way a service depends only on the message header (with the list of the fields and a record id) and the format of the single field it reads (stores data) or writes (retrieves data as Content Enricher [EIP]). That works well with system-wide queries but binds all the services to the schema of the message in a way similar to accessing a shared database (to be discussed below). Such an architecture decouples the services to the extent that any of them can be freely added or removed, together with the message field(s) it fills or reads.

A peculiar feature of choreography is the ability to cut and cross-link pipelines with compatible interfaces by changing a single service (or even system configuration if you build it with communication channels). That gives it a lot of flexibility – as long as you can comprehend all the dependencies (and channels) in the system, which becomes non-trivial as it grows.

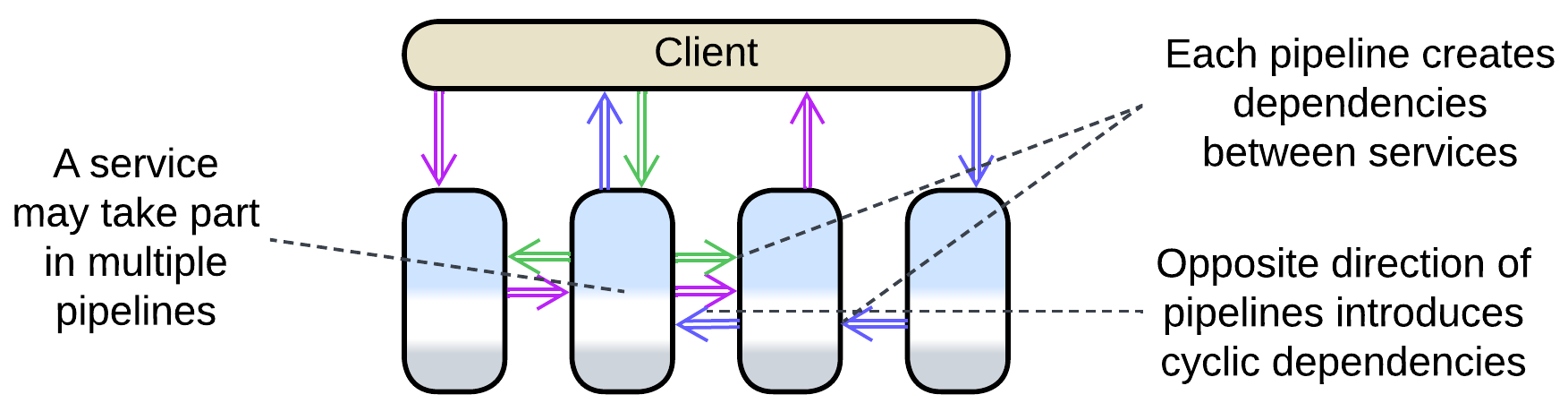

Multi-choreography #

It is very common for a service to participate in multiple pipelines, especially if it owns a database – as there should be a use case which fills in the data and at least one other scenario which reads from that database. Each pipeline makes the service depend on one or more interfaces it communicates with, which often belong to multiple services, coupling components of the system and making it impair future structural changes.

Summary #

Overall, choreography seems to be a lightweight approach that prioritizes throughput over latency and is suitable for highly-loaded scenarios of limited complexity. However, a choreographed system will likely become unintelligible if it is made to support more than a few use cases.

There is a decent overview from Microsoft.