Metapatterns

Is there a way to bring the patterns into order? They are way too many, some obscure, others overly specialized.

We can try. On a subset. And the subset should be:

- Important enough to matter for the majority of programmers.

- Small enough to fit in one’s memory or in a book.

- Complete enough to assure that we don’t miss anything crucial.

Is there such a set? I believe so.

Architectural patterns#

[POSA1] defines three categories of patterns:

- Architectural patterns which deal with the overall structure of a system and functions of its components.

- Design patterns which describe relations between objects.

- Idioms which provide abstractions on top of a given programming language.

Architectural patterns are important by definition (Architecture is about the important stuff. Whatever that is). Point 1 (importance) – checked.

Any given system has an internal structure. When its developers talk about architectural style [POSA1] or draw structural diagrams that usually boils down to a composition of two or three well-known architectural patterns. Choosing architectural patterns as the subject of our study lets us feed on a large body of books and articles that describe similar designs over and over again. Moreover, as soon as a system no longer follows the latest fashions, it is widely advertised as a novelty (or its designers are labeled as old-fashioned and shortsighted), thus we may expect to have heard of nearly all of the architectures which are used in practice. Point 3 (completeness) – we have more than enough examples to analyze.

To organize a set of patterns we rely on the concept of

Design space#

Design space [POSA1, POSA5] is a model that allocates a dimension for each choice made while architecting the system. Thus it contains all the possible ways for a system to be designed. The only trouble – it is multidimensional, maybe infinite, and the dimensions will differ from system to system.

There is a workaround – we can use a projection from the design space into a 2- or 3-dimensional space which we are more comfortable with. However, projection causes a loss of information. Counterintuitively, that is good for us – similar architectures that differ in small details become identical as soon as the dimensions they differ in disappear. If we could only find 2 or 3 most important dimensions that apply equally well to each pattern in the set that we want to research, that is architectural patterns, which cover all the known system designs.

Structure determines architecture#

Systems tend to have an internal structure. Those that don’t are derogatively called Big Balls of Mud for their peculiar properties. Structure is all about components, their roles and interactions. Many architectural styles, for example, Layers and Pipeline, are named after their structures, while others, like Event-Driven Architecture, highlight some of its aspects, hinting that it is the structure which determines principal properties of a system.

I am not the first person to reach such a conclusion. Metapatterns – clusters of patterns of similar structure – were defined shortly after the first collections of design patterns had appeared but they never made a lasting impact on software engineering. I believe that the approach was applied prematurely to analyze the [GoF] patterns, which make quite a random and incomplete subset of design patterns, resulting in an overgeneralization. I intend to plot structures of all the architectural patterns I encounter, group patterns of identical structure together into metapatterns, draw relations between the metapatterns, and maybe show how a system’s structure determines its properties. Quite an ambitious plan for a short book, isn’t it?

Our set of architectural patterns is still not known to be complete, is not small and, moreover, the way structural diagrams are drawn differs from source to source – we cannot compare them unless we make up a universal system of coordinates.

The system of coordinates#

Inventing a generic coordinate system to fit any pattern’s representation, from Iterator [GoF] to Half-Sync/Half-Async [POSA2], may be too hard, but we surely can find something for architectural patterns, as all of them share the scope, namely the system as a whole. Which dimensions an implementation of a system would usually be plotted along?

- Abstractness – there are high-level use cases and low-level details. A single highly abstract operation unrolls into many lower-level ones: Python scripts run on top of a C runtime and assembly drivers; orchestrators call API methods of services, which themselves run SQL queries towards their databases which are full of low-level computations and disk operations.

- Subdomain – any complex system manages multiple subdomains. An OS needs to deal with a variety of peripheral devices and protocols: a video card driver has very little resemblance to an HDD driver or to the TCP/IP stack. An enterprise has multiple departments, each operating a software that fits its needs.

- Sharding – if several instances of a module are deployed, and that fact is an integral part of the architecture, we should represent the multiple instances on our structural diagram.

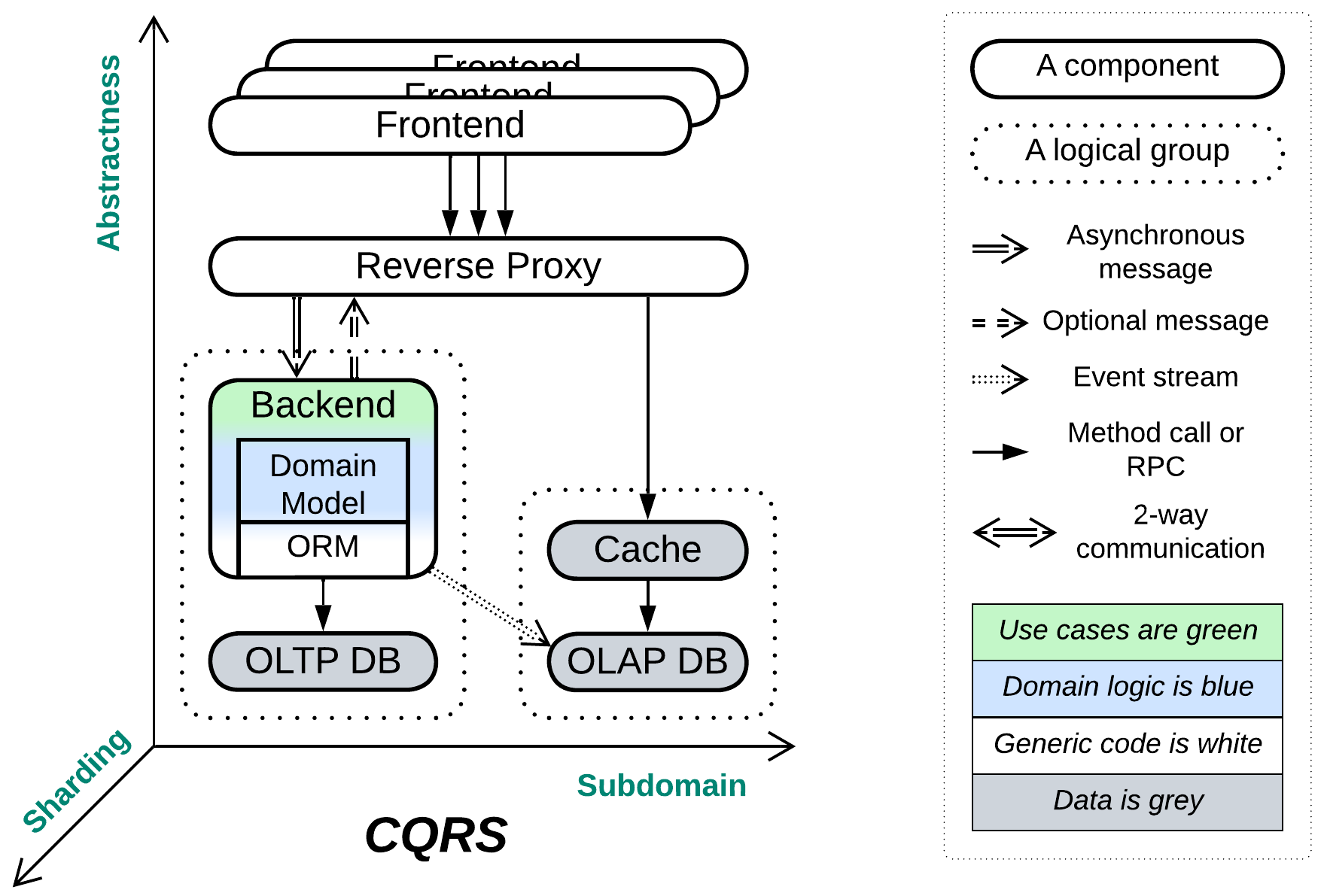

We’ll draw the abstractness axis vertically with higher-level modules positioned towards the upper side of the diagram, the subdomain axis horizontally, and sharding diagonally. Here is an (arbitrary) example of such a diagram:

(A structural diagram for CQRS, adapted from Udi Dahan’s article, to introduce the notation)

Map and reduce#

Now that we have the generic coordinates which seem to fit any architectural pattern, we can start mapping our set of architectural patterns into that coordinate system – the process of reducing the multidimensional design space to the few dimensions of structural diagrams which we were looking for. Then, after filtering out minor details, our hundred or so of published patterns should yield a score of clusters of geometrically equivalent diagrams – just because there are very few simple systems that one can draw on a plane before repeating oneself. Each of the clusters will represent an architectural metapattern – a generalization of architectural patterns of similar structure and function.

Let’s return for a second to our requirements for classifying a set of patterns. The importance (point 1) of architectural patterns was proved before. The reasonable size of the resulting classification (point 2) is granted by the existence of only a few simple 2D or 3D shapes (metapatterns). The completeness of the analysis (point 3) comes from, on one hand, the geometrical approach which makes any blank spaces (possible geometries with no known patterns) obvious, and on the other – from the large sample of architectural patterns which we are classifying.

Godspeed!

An example of metapatterns#

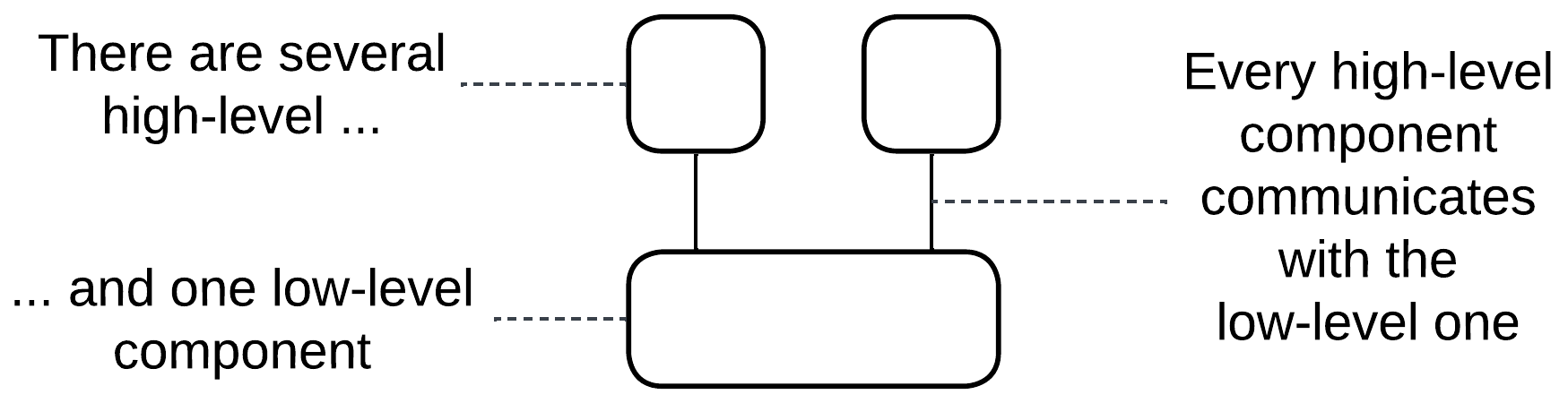

Let’s consider the following structure:

It features two (or more in real life) high-level modules that communicate with/via a lower-level module. Which patterns does it match?

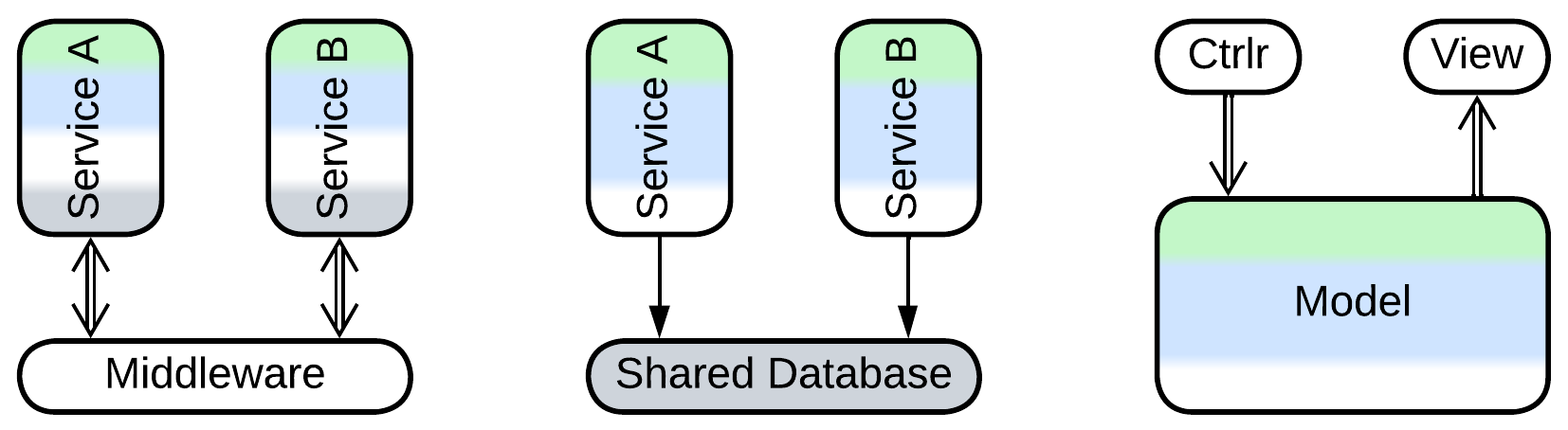

- Middleware – a software that provides means of communication between other components.

- Shared Database – a space for other components to store and exchange data.

- Model-View-Controller – a platform-agnostic business logic with customized means of input and output.

My idea of grouping patterns by structure seems to have backfired – we got three distinct patterns that have similar structural diagrams. The first two of them are related – both implement indirect communication, and their distinction is fading as a Middleware may feature a persistent storage for messages while a table in a Shared Database may be used to orchestrate services. The third one is very different – primarily because the bulk of its code, that is its business logic, resides in the lower layer, leaving the upper-level components a minor role.

Notwithstanding, each of the patterns we found is a part of a distinct cluster:

- Middleware is also known as (Message) Broker [POSA1, POSA4, EIP, MP] and is an integral part of Message Bus [EIP], Service Mesh [FSA], Event Mediator [FSA], Enterprise Service Bus [FSA] and Space-Based Architecture [SAP, FSA].

- Shared Database is a kind of Shared Repository [POSA4] (Shared Memory, Shared File System), and the foundation for Blackboard [POSA1, POSA4], Space-Based Architecture [SAP, FSA], and Service-Based Architecture [FSA].

- Model-View-Controller [POSA1, POSA4] is a special kind of Hexagonal Architecture (aka Ports and Adapters, Onion Architecture and Clean Architecture) which itself is derived from Plugins [PEAA] (Addons, Plug-In Architecture [FSA], or the misnomer Microkernel Architecture [SAP, FSA]).

Our touching on a single geometry of structural diagrams revealed a web of 20 or so pattern names that spreads all around. With such a pace there is a hope of exploring the whole fabric which is known as pattern language [GoF, POSA1, POSA2, POSA5].

There are three lessons to learn:

- The distribution of business logic is a crucial aspect of structural diagrams.

- Metapatterns are interrelated in multiple ways, forming a pattern language.

- Each metapattern includes several well-established patterns.

What does that mean#

Chemistry has the periodic table. Biology has the tree of life. This book strives towards building something of that kind for software and systems architecture. You can say “That makes no sense! Chemistry and biology are empirical sciences while software architecture isn’t!” Is it?