About this book

When I was learning programming, there was Gang of Four. The book promised to teach software design, and it did to an extent with the case study provided. However, the patterns it described were merely random tools which had little in common. After several years, having reinvented Hexagonal Architecture along the way, I learned about Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture. The series had many more intriguing patterns, and promised to provide a system of patterns or a pattern language, but failed to build an intuitive whole. Then there were specialized books with Domain-Driven Design and Microservices patterns. There was the Software Architecture Patterns primer by Mark Richards. Its simplicity felt great, but it had only 5 architectural styles, while his next book, Fundamentals of Software Architecture, dived too deeply into practical details and examples to be easily grasped.

Now, having leisure thanks to the war, burnout, unemployment and depression I have had a chance to collect architectural patterns from multiple sources and build a taxonomy of architectures. My goal was to write the very book I lacked in those early years: a shallow but intuitive overview of all the software and system architectures as used in practice, their properties and relations. I hope that it will be of some help both to novice programmers as a kind of a primer on the principles of high-level software design and to adept architects by reminding them of the big picture outside of their areas of expertise.

The book is mostly technology-agnostic. It does not answer practical questions like “Which database should I use?” Instead it inclines towards the understanding of “When should I use a shared database?” Any specific technologies are easy to google can be found over the Internet somewhere in the Noosphere.

This book started as a rather small project to prove that patterns can be intuitively classified (These nightmarish creatures can be felled! They can be beaten!) but grew into a multifaceted compendium of a hundred or so architectures and architectural patterns. It is grounded in the idea that software and system architecture evolves naturally, as opposed to being scientifically planned. Thus, the architectures may exhibit fractal features, just like those in biology – merely because the set of guidelines and forces remains the same for most systems that range from low-end embedded devices to world-wide financial networks. Moreover, in some cases we can see the same patterns applied to hardware design.

The idea of unifying software and system architecture is heretical. I am well aware of that. Still, the industry is in the early stage of alchemy these days: the same things are sold under multitudes of names, being remarketed or reinvented every decade. If this book manages to provide rules of thumb, similar to those of biology (a bat is a mammal, thus it should run on all four, while ostriches, as birds, must fly to Europe each spring), I will be happy with that. Science makes progress funeral by funeral.

The latest version of the book is available for free on GitHub and LeanPub, and can be read online. As there is no one who has practiced all the known architectures, it will be full of mistakes. I rely on your goodwill to correct them and improve the text. Critical reviews are warmly welcome: please write an email or contact me on LinkedIn.

Structure of the book#

The first chapter explains the main idea which makes this book different from others. The following chapters in the first part touch on several general topics that are referenced throughout the book.

The next four parts iterate over metapatterns (clusters of closely related architectural patterns), starting with the simplest one, namely Monolith, then heading towards more complex systems that may be derived from Monolith by repeatedly dissecting it with interfaces. Each chapter describes a group of related patterns that share benefits and drawbacks, adds in a few references to books and websites, and summarizes the ways the patterns can be transformed into other architectures. The format of these chapters is described in Appendix F.

The sixth part of the book is analytics – the fruits of the pattern classification from the earlier parts.

Finally, there are appendices. Appendix B is the list of the books referenced, Appendix E contains detailed evolutions of patterns and Appendix I is the index of the patterns found in the book.

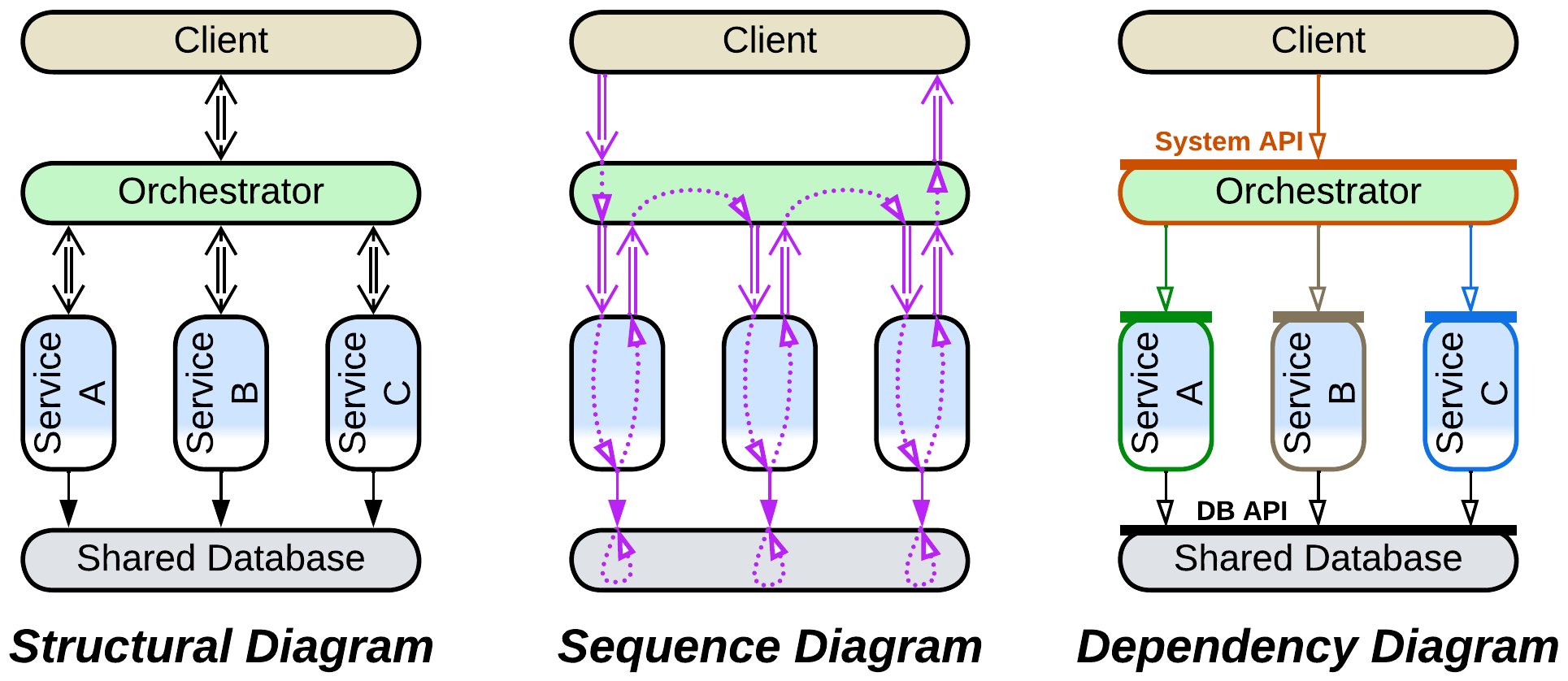

Diagrams#

This book makes heavy use of diagrams – to the extent that it can be treated as a kind of visual novel. As it is mostly made of patterns, and each pattern is an island, it must not be read sequentially – instead, the reader is advised to use the plentiful cross-links to open whatever (if any) content found to be intriguing and check the corresponding diagram. If it gets your attention, you may read the text below it. If you like the text, you may scroll up or down to see if there are more funny diagrams nearby.

The diagrams are NoUML and most of them belong to one of the following kinds:

Components in the diagrams are colored according to the kind of code they contain:

- Use cases (application logic) are green.

- Business rules (domain logic) are blue.

- Generic code is white.

- The data is gray.

Please refer to the following chapter for the system of coordinates used in the diagrams.

Notation#

- Pattern names are given in Title Case Italics and usually link to the pattern’s definition.

- The first mention of a term or a name of a pattern component is italicized.

- Quotes and puns are in full italics.

- Book references are [BRACKETED] and link to the list of the books in Appendix B.

Supplementary explanations are grayed-out.

Many patterns match terms of the common language – indeed, as a pattern is a generalization of human experience, the more widespread a notion, the faster it is turned into a pattern. Such general-use terms, e.g. layers, services or pipeline, are usually not indicated in any way to preserve the overall readability.

The architectural religions#

There are several schools of software architecture:

- The believers in SOLID.

- The followers of eight qualities, five views and as-many-as-one-gets certifications.

- The aspirants to the nameless way of patterns.

In my opinion:

- SOLID is a silver bullet that tends to produce a DDD-layered kind of Hexagonal Architecture. It lacks the agility of pluralism found with evolutionary ecosystems.

- Architectural frameworks are overcomplicated thus hard to understand and inflexible.

- Patterns are like a kind of toolbox, the one which a mechanic is often seen carrying around. A skilled craftsman knows best uses of his tools, and can invent new instruments if something is missing in the standard toolset. However, the toolset’s size should be limited for the tools to be familiar to the practitioner and easily carried around.

It is likely that those approaches are best used with systems of different sizes: SOLID is aimed at stand-alone application design while the heavy frameworks and certifications suit distributed enterprise architectures. In such a worldview patterns span everything in between the two extremes.

What’s wrong with patterns#

Too much information is no information or, as they say, what is not remembered never existed. There are literally thousands of patterns described for software and system architectures. Nobody knows them all and nobody cares to know them all (if you say you do, you must have already read the Pattern Languages of Programs archives. Have you? Neither have I). Hundreds of patterns are generated yearly in just the conferences alone, not to mention the books and software engineering websites. Old patterns get rebranded or forgotten and reinvented. This is especially true for the discrepancy between the pattern names in software architecture and system architecture. The new N-tier is just good old Layers under the hood, isn’t it?

This undermines the original ideas which brought in the patterns hype:

- Patterns as a ubiquitous language. Nowadays similar, if not identical, patterns bear different names, and some of them are too obscure to be ever heard of (see the PLoP archives).

- Patterns as a vessel for knowledge transfer. If an old pattern is reinvented or plagiarized, most of the old knowledge is lost. There is no continuity of experience.

- Pattern language as the ultimate architect’s tool. As patterns are re-invented, so are pattern languages. At best, we have domain-specific or architecture-limited (DDD, Microservices) systems of patterns. There is no single unified vision which pattern enthusiasts of old promised to provide.

Have we been fooled?

TLDR#

Compare Firewall and Response Cache. Both represent a system to its users and implement generic aspects of the system’s behavior. Both are Proxies.

Take Saga Execution Component and API Composer. Both are high-level services that make a series of calls into an underlying system – they orchestrate it. Both are Orchestrators.

It’s that simple and stupid. We can classify architectural patterns.